Operation Oleander (9780547534213) (15 page)

Read Operation Oleander (9780547534213) Online

Authors: Valerie O. Patterson

His letter goes on:

Â

I was going to mail them to Mr. Scott along with the rest of Mrs. Scott's belongings. Word came he didn't want us to return the camera. So we've given it to the orphanage. But we weren't sure what to do with the photos and theâmemory card. We didn't want to destroy them. We thought of your dad, but he's in Germany and soon to be stateside. That leaves you, Miss Jess, because there is no one else who would appreciate more what these photos mean. So we turn them over to the custody of Operation Oleander.

Sincerely,

Frank Johnson

Â

With shaking fingers, I slip off the rubber band. The first photo shows several of the girls playing with a ball. Another one was taken outside the orphanage doors, in the courtyard. That's where the bomb exploded a few minutes or so later. Had the army looked at these photos as part of the investigation into what happened? Or were these duplicates and, somewhere, Mrs. Scott's photos had become part of the official record?

The last photo is of Warda by herself. She's standing alone near the doorway, her hand on the wall. Oleander bushes grow on one side. Warda stares right into the photo, as if Mrs. ScottâCorporal Scottâhad gotten her to look into her eyes and the camera lens wasn't even separating them. That's how intense the look is. How close.

I clutch the photo to my chest.

Almost as if they'd both known.

Impossible.

Mr. Johnson was partly wrong, though. There is someone else who will appreciate these photos as much as me. Maybe more.

Meriwether.

“Mrs. Johnson, we have to get copies of these photos made. Today.”

“Hold on. What are you talking about?”

“Mr. Johnson sent photos and letters from the orphanage.”

Mrs. Johnson shakes her head. “That Frank, he's a sentimental one. Never know it to look at him.”

“You don't understand. The best news. Warda's still alive.” I hold up the photograph of Warda that Mr. Johnson had sent, one of the ones taken by Mrs. Scott.

Mrs. Johnson squints at the photo. “That's the girl in the photos at the fundraiser?”

“Yes, she was there the first day my dad and the others took supplies.”

The stone I keep hidden away. That's my secret.

“Mrs. Scott took this photo,” I say. “All of these.”

Mrs. Johnson touches the photos, as if touching them makes them more real. “I'll be . . .”

“We have to get copies made. Now.”

Mrs. Johnson frowns at me. “It can wait until after lunch.”

“Now. I want to go now. I want to get them to Meriwether.”

A

FTER WE

get back with the duplicate photos, I phone Sam first, afraid Commander Butler will answer the phone and say something about the article in the

Clementine Times.

But Sam answers.

“You won't believe what I have.”

“What?” he asks.

“Photos. Photos of the orphanage that Meriwether's mother took that day.” The day of the explosion.

“Really?”

“Yes, Mr. Johnson sent them. I've made copies. A set for you. A set for Meriwether. Will you come with me?”

“Where?”

“To Meriwether's house. I want you to be there when I give them to her.” All of us together. All of Operation Oleander.

Sam doesn't answer right away. He shuffles from one foot to the other. I can tell even through the phone line.

“Okay, I'm coming,”

Sam meets me at the corner of Madrid, and we bike to Meriwether's house together. Like we used to.

This time the Scotts' car is there, parked on the street. The curtains are open. But in the driveway there's a moving van. It's backed up to the carport, and men are loading it with boxes and furniture wrapped in heavy quilting.

The thud of the moving boxes echoes in my heart. I am the day lilies Meriwether dug up. The missing dragonfly garden stake. I am all the things being ripped away.

They have to move off post. Everyone knows that. But not so soon. They're going farther, to South Carolina, for now.

“Did you know they were moving today?” I ask Sam.

He nods. “Mom told me.”

“Why didn't you say anything?” We are best friends, Meriwether and me. And Sam.

He shakes his head. “Couldn't.”

“More duty, honor, country?” Is he just like his dad after all?

“No,” he says. “It was one more sad thing.”

I blink back tears. No crying here.

“Come on,” I say.

We pick our way through the chairs and tables waiting to be loaded. Dodge packers and movers who work like robots, knowing how to be efficient.

Inside the living room, it already feels like a stranger's house.

“Jess, Sam.” It's Mr. Scott. He waves us toward the hallway and the kitchen beyond, where the lighting shows off the azure tiles.

My heart beats hard. The last time I saw Meriwether was at the funeral. The last time I was here before that, I tried to give Meriwether an album. An album of photos of us. It's back at home in a drawer. If I'd known they were moving today, I'd have brought it. Even if Meriwether rejected it. I could have hidden it in the moving van, and she'd find it later, when she might want it.

Sam and I join Mr. Scott, who's standing next to the sink, a cup in his hand. He looks like he's having a morning cup like any other morning and the chaos around him doesn't bother him. As if he doesn't see any of it.

“We have something for Meriwether. And for you.” I hold out the packet of processed photographs.

“Meriwether?” Mr. Scott calls out the back window.

When Meriwether walks in, we all stand straight and silent in four corners of the kitchen, walled in by the blue tiles that always made me smile.

“Mr. Johnson sent me these photosâ”

“I don't want them.” Meriwether folds her arms.

“They'reâ”

“I told you I don't want them.” She and her dad don't look at the package.

“I can explain.” I look to Sam, and he nods but doesn't say anything. “That day, that day at the orphanage, your mom took photos.”

Meriwether's foot is tapping, and her arms are so tight across her chest, her hands are clenched. My hands are shaking, just a little, but enough so the paper bag crinkles. “She took photos of the children and my dad. They are the last images she captured on film.” They are what she saw.

Mr. Scott clears his throat.

“Photos of the orphanage? Really, Jess?” Meriwether's eyes whip like frothy wind-tossed waves. “What makes you think I want them?”

“Because your mom took them.”

Mr. Scott's hands clench together in front of him. Meriwether doesn't budge.

“I'll just leave them here, on the counter.” Where the movers won't throw them out as trash. “We'll go, Sam and me. Please write and tell me where you are.” South Carolina.

I ease the photos onto the counter space, and Sam and I leave through the front hallway.

Finally, outside, I can breathe again.

“It's not your fault, Jess,” Sam says after we start biking back toward my house.

I nod, but I don't believe him. Not really.

“I'm going to talk to your dad again,” I say.

He hits the brakes and stops. “What?”

“I'm going to ask him about restarting Operation Oleander.”

Sam gives me one of his looks, the looks I have trouble reading. “Okay.”

Okay? That's it? He doesn't argue. I don't believe him.

“I've been thinking about what else we could do. For when your dad lifts the ban. I did some research online. We could donate everything we get to a national organization that provides for an Afghanistan aid center,” I say.

“I'm listening.” Sam twists the handlebars on his bike.

“That way there's no link between the U.S. military and the orphans. I liked knowing that what we had done we did ourselves. But it's more important that the supplies get where they're needed. The safest way for everyone.”

“It might work.”

Â

The next morning, I head over to the PX. The table for the snack sales is already unfolded and in its place. I just need to unlock the closet and unpack, then add some information about the Afghanistan Aid organization I researched.

“Reporting for duty,” a voice says.

I look up.

Sam's standing in front of me, saluting.

Next to him, Aria clutches a stiff poster board. On it she's made a collage with photos of Warda and the others.

Suddenly, I am standing on the edge of a cliff again. Dizzy, the way I felt when Meriwether told me about deleting her mother's voice-mail message. When I think about the destruction done by the insurgents, the bombings, the anger and hatred of the Angustus

protesters with their signs. Both sides of hatred, each claiming the other is evil.

“Aria, do you agree to the membership duties of Operation Oleander.”

“Yes,” she says.

“Duties?” Sam asks.

“Like duty, honor, country. Only ours are different in some ways. Giving isn't always only a good thingâ I know that now. Even good motives lead to unintended consequences. But I'm not giving up. And neither is Operation Oleander.”

I continue. “Giving matters. Each small gift together. Maybe that's all that matters.” Giving without the thought of return. Not for a gold star. Or to make Dad proud. Not even for the internal joy. I distrust my own heart.

“Father Killen said that we should do it, follow the form. And the substance will come,” I say.

“He was talking about prayer, Jess,” Sam said. “He always says that.”

“I know that. But giving is a form of prayer too.”

Through the fabric of my pocket, I feel the stone. A stone that is my own gift, my own shared prayer of life.

“If one orphan benefits, isn't that good enough?” Aria asks.

I salute them back.

Yes.

Â

That afternoon, it's raining again. I've taken an umbrella and walked to the street in my flip-flops to get the mail.

Mr. Scott pulls his car up to the curb, and Meriwether bolts from the passenger side without an umbrella. I stand on the sidewalk, not sure whether to go to her or back away. I wait for her anger to crest over me like a rogue wave, my body stiff.

“Don't. You're getting soaked,” I say.

But Meriwether grabs onto me in a hug that crushes my lungs.

“Jess” is all she says. I hug her back. Without her telling me, I know the photos her mom took are going with her. They are the gift she can hold on to.

“Wait, don't leave,” I tell her. I give her my umbrella and run for the house.

Mrs. Johnson says, “What theâ?” when I crash into the living room and down the hall, my flip-flops squeaking from the rain. In my room I find the album still in the tote bag. I race back outside.

“Here. Take this. It's for you. It's an album. Of us. I've been saving photos since last year.”

Meriwether shelters the album as she carries it to the car and stashes it inside, out of the rain.

Then she reaches for something in the back seat.

“I want you to have some of these.”

Day lilies.

“Please take care of them,” Meriwether says. “Mom loved them.”

A flash of lightning singes the air.

The thunder booms, and Meriwether and I hug hard one last time before she leaves.

From under the dry carport, I turn and wave at the Scotts. The rain is coming down so hard, I can't see them through their car windshield. But I know they are waving too.

I hold the burlap-wrapped day lilies tight in my arms. They're my orphans too, like Warda and the other children.

The Scotts' car turns at the end of the block. Later, whoever moves into their house won't know the day lilies left in the yard belonged to Mrs. Scott. They won't know that she planted them carefully, babied them. Or how much she loved them. Whoever moves in next

might even replace them with other landscaping.

But I know what they're called.

Hemerocallis.

From the Greek for “beauty for a day” because each bloom lasts for only about twenty-four hours. Just a single day, and I think about what Mrs. Scott said: “Life is too short not to plant flowers.”

I won't forget these links between us. Between Mrs. Scott and Meriwether. Between Meriwether and me. Between us and the orphans in Afghanistan whom we will never know in person.

I will call them all by name.

Â

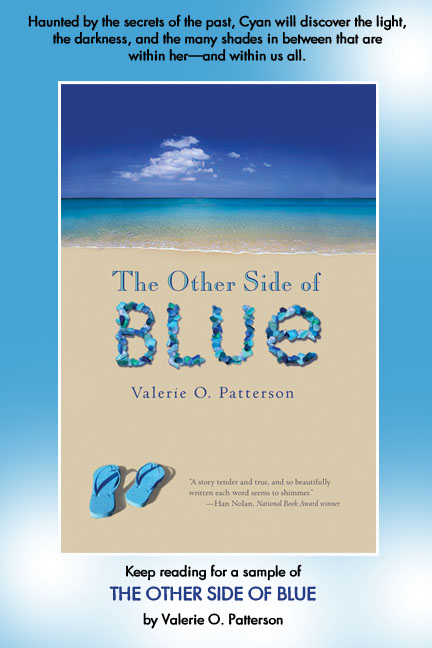

Chapter One

Â

WE'RE IN PARADISE, so the tourist brochures say. That's what I thought, too, before last June, when the unspeakable happened, when Dad took the blue boat out and didn't come back.

The Caribbean island of Curaçao beckons sun worshipers and cruise ships that sail up St. Anna Bay and dock near the House of the Blue Soul. Taffy pink, aqua, and lemon yellow buildings like squares of colored candies line the streets of Willemstad's shopping district.

Bon bini

signs welcome arrivals at every port of call, the airport, and almost every shop in Punda and Otrobanda. They're even plastered to the side of boats taking tourists out to scuba-dive in deep water.

Paradise.

Where the water is so blue, so calm, so deceptive.