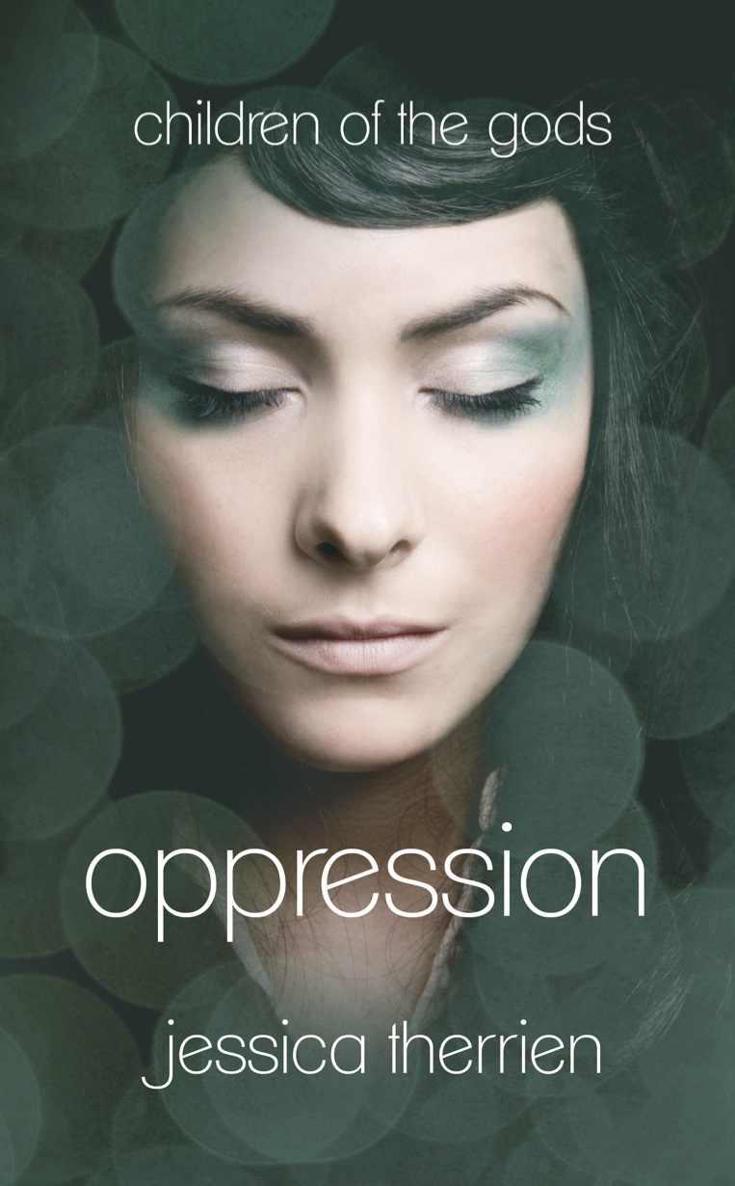

Oppression

Authors: Jessica Therrien

Children of the Gods

BOOK 1

Oppression

Jessica Therrien

ZOVA

Books

Los Angeles

ZOVA

BOOKS

This book is a work of fiction. References to real people, events, establishments,

organizations, or locales are intended only to provide a sense of authenticity and are used fictitiously. All other characters, and all incidents and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real.

First ZOVA Books edition 2012.

OPPRESSION. Copyright © 2012 by Jessica Therrien

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of t

his book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information or permission contact:

ZOVA Books

P.O. Box 21833, Long Beach, California 90801

www.zovabooks.com

ISBN 13: 9780984035045

ISBN 10: 0984035044

Cover Design © Daniel Pearson

to my mother and sister

for being my cheerleaders along the way.

And to my husband for being my inspiration.

1.

IT WAS DECEMBER 12, 1973. I remember because it was my fiftieth birthday, and Christmas was coming, so the snow was to be expected. In this area of northern California, we rarely saw anything but a white Christmas. Chilcoot was nestled high up in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. A small rectangular green sign was the only evidence that the small town actually existed: Chilcoot, California, Elevation 5000 ft, Population 58. A distracted driver could easily pass through the two-mile stretch of road that touched its borders without realizing he’d seen it.

We were on our way into the city, the closest to our house being over an hour away, and Daddy was grinning ear to ear as he drove his new forest green Cadillac Coupe de Ville into the oncoming flurries. He loved that car.

“Now, make sure the tree is sturdy, Elyse, and nice and tall,” Daddy said.

“I know, Dad. I think I’ve picked enough trees in my life to know a good one. Besides, you never let me choose it anyway,” I mumbled under my breath. I saw my mother’s cheeks lift into a smile. She must have heard me, and she knew it was the truth. We’d had this birthday tradition for the last twenty years. I was supposed to be the one to pick out the Christmas tree, but my choices hardly ever passed Daddy’s final inspection.

“Don’t you like this one?” he’d ask. “Yours is a little thin on the bottom. This one’s much better, right?”

“Right,” I would mutter mechanically.

“See, Sarah, she’s a good sport, knows a good one when she sees it.”

My mother never argued. He was too much of a perfectionist to let anyone else handle those sorts of things. It was kind of funny really, one of his little eccentricities that I overlooked in my youth.

It was two o’clock in the afternoon, but the day was dim. The sun had been swallowed up by the all-consuming white. I was gazing out the back window as it happened, trying to judge the visibility through the whiteout. I couldn’t see far, just beyond the edge of the fence that ran alongside the road.

“Richard, slow down!” my mother shouted. The words triggered the incident like she had seen it coming. The car drifted into the next lane, and I felt the loss of control as the paved road became slick ice. My body stiffened in response to the awkward gliding sensation, and I braced myself for the impact. Every second of the slow motion tumble seemed an eternity as I prepared for the last moments of life. I clung to those seconds, taking in the final images that my eyes would see, and listening for the closing lines that would mark the end.

“Ellie!”

My mother’s panicked voice rang out in the hollow silence of the cab with a sort of knowing uncertainty just before we hit.

***

It had been thirty-nine years since the accident, and still these photos stirred up the last memory I had of them. I stared down at the faded pictures, the delicate paper worn on the edges. I would never forget. The last words of my parents, the flickering image of a deep red that stained the snow like an open wound on the skin of the earth, and the crumpled Cadillac flipped over in the bank.

The photos were old, too old for me to be in them, but I was. My mother’s silky brown hair billowed over her shoulders, and I was glad I still remembered the rich chocolate color of it because the gray and white image didn’t do it justice. The lack of color masked her would-be golden brown eyes and rosy cheeks. She was gorgeous. My father, to her left, was looking far too concentrated on the camera, furrowed brow and closed mouth. His skin, dark from working in the sun, nicely contrasted his short blond hair which he wore parted and combed to the side. I was at his feet, and we were posing in front of the tree like a typical storybook family. It was the Christmas of 1939. I looked three years old, but in truth, I was much older.

I was born in 1923 with a rare genetic abnormality. Like my mother and father, I aged five times slower than the average person. I’d been alive for eighty-nine years making me almost eighteen in the eyes of the rest of the world, and for the most part I felt young. I was living in San Francisco now. I found the city much easier to hide in than the small towns I had been moving to every five years or so since their death. In the city, I was just another face, another body in the crowd, completely invisible amongst the masses.

“We’ve gone to great lengths to live as we do, Ellie. It’s for your safety,” my father had always insisted. “Our bodies are durable and strong, but that’s a blessing and a curse. The secrecy of our identities is precious, and there is no telling what could happen if we were to be found out. People like us could not live a normal life if we were exposed.”

It was all I ever learned about myself and why I was so different, why I had to live in secret. Looking back, there was so much more I wanted to know, so many unanswered questions. What about my grandparents? What about my future? Was I destined to be alone? How did my parents find each other? Were there others? My father never went into detail. Instead, he avoided my questions, always suggesting a distraction that would divert my attention for a while.

“In time you’ll learn to live under the radar as we’ve done. For now, why don’t we get you a puppy?”

They bought me a Border Collie. She was black with white spots and white feet. I named her Sweetie, and I loved her like I had never loved anything. She went with me everywhere, and in my friendless world, Sweetie became the best friend I’d ever had. The attachment we’d formed seemed unbreakable, but as nature would have it, Sweetie died when I was nine. On that day, I fully understood why my parents had not wanted me to have friends—friends who I would love, who would age, and leave, and die.

The phone rang loud and unexpected, waking me out of my nostalgia. I returned the old photos to the small gold chest I kept them in and stumbled over unpacked boxes trying to get to the receiver. I had just moved in about two weeks ago, and the naked living room, void of furniture, was a scattered mess. I picked up on the third ring, still lost a little in my own head.

“Hello?” I answered, expecting the only person who had my number.

“Ellie?”

“Hey,” I said, happy to hear from her. “I know I haven’t called. Sorry.”

I caught my reflection in the hallway mirror, still so young. My dark brown hair was tied back in a loose ponytail, my cheeks wrinkle-free and rosy. I felt guilty listening to Anna’s older voice. Over the years, she’d become a woman of forty-eight, and I’d barely changed.

“Are you moved in?” she asked, excited.

I sighed, looking around at the cluttered floor. “Getting there.”

“How are you?”

“Okay,” I lied.

She knew me too well. “You want to come over?”

“I don’t know. Not yet. I know it’s been a while but . . .”

“I’m sorry,” she said. What are people supposed to say when your second mother dies?

“I still wake up and listen for her thinking maybe I dreamed it.”

“She lived a long, happy life, Elyse. Eighty-nine years is longer than most of us get.”

“You know that’s how old I am, right?”

“I know.”

I felt my throat tighten and the tears come. There was no stopping it. Hadn’t I cried enough?

“So, how are you?” I asked, throwing myself back into the conversation. I didn’t want to think about Betsy’s age. “How’s Chloe?”

“I’m good,” she answered. “Yeah, I’m good.” I heard the pain in her voice, the fear, the worry. “Chloe misses you. She’s worried about you. We both are.” Her words hung in the air.

Talking about it was too much. “I, um, have to call you back, Anna.”

I had to get out. Sulking wasn’t going to do me any good. I would go to the grocery store. I needed food. I needed buckets of ice cream to get me back to a normal weight. Betsy would have been so angry.

“You’ve got no meat on your bones,” she would have said. “It’s not healthy, Elyse.” I could imagine her aged brow creased in the center, her lips pressed together in disapproval. I missed that look. There was so much love behind it, such motherly concern.

I tried all day not to think about Betsy. I watched movies, cleaned and unpacked, read, did crosswords. Now here I was again remembering. It seemed like all there was to do was remember. After a while, I let myself give in to the urge and stopped resisting the memories. They flooded me with all their weight—an avalanche of nostalgic sorrow burying me in the depths of my own mind.

The daylight broke through the open blinds of my bedroom window, waking me before my alarm. I glanced at the clock by my bed with a sigh, 7:22 a.m. The memories of life with Betsy had continued throughout the night, weaving in and out of my dreams. I suppose that was to be expected. She had arranged all of this for me, a new social security number, a license, a place to live. She had prepared me to start a new life, prepared me for her death in a way. I owed her those memories.

Today, I needed to look for some sort of job to keep me busy. It wasn’t that I needed the money. My parents and Betsy had set plenty of that aside for me. But I wanted to be done grieving. It seemed like no matter what I did, I couldn’t escape the guilt I felt for having so much more life to live. I knew eventually I would have to learn to turn my emotions off—witnessing death just seemed to be part of my existence—but for now it was out of my hands.

Although I’d been here a couple of weeks already, I still wasn’t used to my new place. It didn’t feel at all like home. My unit was one of three that sat above a café in the Lower Haight on the corner of Waller and Steiner. It was a classic-looking building with a vintage façade. There was a door for each apartment lining the sidewalk, all opening to narrow stairs which led up to the second story. The entry opened into the left side of the kitchen with its blue and white plastic floor and maple cabinetry, and transitioned into the living room with a simple change in flooring, from linoleum to tight knit gray-blue carpet. To the right of the living room was a single hallway with a bathroom on the left and a solitary bedroom on the right.

My clothes were still packed away in the suitcases I’d brought them in. I wasn’t a complicated girl, so it didn’t affect my lifestyle much. I chose whatever outfit was on top, usually jeans and an old baseball shirt. I wasn’t trying to impress anyone. In fact, I was aiming for the opposite, so it didn’t matter much what I walked out the door wearing.

I wasn’t used to public transportation, but the Bay Area had an underground metro system close by, a convenience I was still growing accustomed to. I didn’t intend on stopping at the café downstairs on my way out, but I was looking forward to passing by the place this morning. It was a silly reason, one I probably wouldn’t admit to anyone if they asked. From time to time

he

would be there, one of the workers at the coffee shop. I didn’t know his name, but he seemed to linger outside, clearing tables or taking his break.

We’d never spoken a word to each other, at least verbally. Most of the time our eyes did the talking. A quick smile said enough. It was an innocent exchange, safe, yet exciting.

As I headed down the stairs, the thought was trivial and foolish, but I hoped he’d be there. The last time I had seen him, he’d been leaning against the wall, digging his shoe into the concrete waiting for someone. His arms were crossed, head down, his hair falling forward, following his downward gaze. He didn’t see me at first, but as I passed by, he looked up and directly at me. His expression was pleased, as if he’d been waiting for me. When our eyes met, it was like he’d known me for years, as if we’d already shared a hundred secrets. Or maybe that was what it looked like when two people were in love. I shouldn’t think like that, I thought, reprimanding myself for even considering the idea.

When I stepped out the door and didn’t see him, I sighed with disappointment. I took my time rummaging through my bag and locking my door. Despite my stalling, he didn’t show. It wasn’t like me to care so much about these things. I didn’t allow myself to get involved with people. I should think of his absence as a good thing, less of a temptation. Still, I found myself staring at the sign that read CEARNO’S for far too long. I don’t know what possessed me, but I decided to go in. I hadn’t eaten yet this morning. That’s how I justified it.

It was my first time inside the café. In full daylight, it didn’t brighten up the way it should. The only windows were at the front of the store, and even those were covered by long brown curtains—but it was comfortable, like the den of an old friend’s house. Cushioned seats lined the walls and a jukebox sat next to a pool table in the far right corner.

“What can I get for you?” asked a young guy from behind the counter. It was him.

When our eyes met, I lost my ability to speak. He was gorgeous, and I felt intimidated. What did he ask me? I was too busy trying to figure out what it was about his handsome face and soft mouth that had me so flustered.

“Cat got your tongue?” he teased, tucking his grown out waves of golden hair behind his ears. He stared into me as I tried to understand the connection, the mysterious closeness between us that I couldn’t put my finger on.