Oral Literature in Africa (2 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

Online Resources

This volume is complemented by original recordings of stories and songs from the Limba country (Sierra Leone) which are freely accessible at:

http://www.oralliterature.org/collections/rfinnegan001.html

Ruth Finnegan’s Limba collection was recorded during her fieldwork in Limba country in northern Sierra Leone, mainly in the remote villages of Kakarima and Kamabai. Recorded mostly in 1961, but with some audio clips from 1963 and 1964, the collection consists of stories and occasional songs on the topics of the beginning of the world, animals and human adventures, with some work songs and songs to accompany rituals also included.

Performances were regularly enlivened by the dramatic arts of the narrator and by active audience participation. Songs in this collection are accompanied by the split drum (gong) known as Limba

nkali ki

, although story songs are unaccompanied. The predominant language of the recordings is Limba (a west Atlantic language group), with occasional words in Krio (Creole), which was rapidly becoming the local lingua franca at the time of the recordings.

Illustrations

Frontispiece: The praise singer Mqhyai, distinguished Xhosa imbongi, in traditional garb with staff (photo courtesy Jeff Opland).

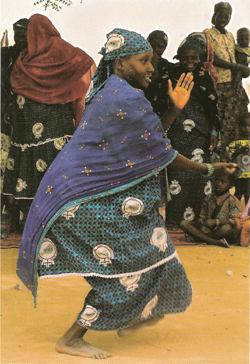

Dancer, West Africa (photo Sandra Bornand). | |

The author on fieldwork in Limba country, northern Sierras Leone, 1964. | |

Nongelini Masithathu Zenani, Xhosa story-teller creating a dramatic and subtle story (photo Harold Scheub). | |

Mende performer, Sierra Leone, 1982 (photo Donald Cosentino). | |

Dancers from Oyo, south West Nigeria, 1970 (photo David Murray). | |

‘Jellemen’ praise singers and drummers, Sierra Leone (Alexander Gordon Laing Travels in the Timmannee, Kooranko and Soolima Countries, 1825). | |

‘Evangelist points the way’ Illustration by C. J. Montague. From the Ndebele edition of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, 1902. | |

Arabic script of a nineteenth-century poem in Somali (from B. W. Andrzejewski ‘Arabic influence in Somali poetry,’ in Finnegan et al 2011). | |

Reading the Bible in up-country Sierra Leone, 1964 (photo David Murray). | |

Tayiru Banbera, West African bard singing his Epic of Bamana Segu (photo David Conrad). | |

Songs for Acholi long-horned cattle, Uganda, 1960 (photo David Murray). | |

Funeral songs in the dark in Kamabai, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Limba girls’ initiation, Biriwa, Sierra Leone, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Ceremonial staff of Ogun, Yoruba, probably late eighteenth century. | |

Limba work party spread out in the upland rice farm, inspired by Karanke’s drumming, Kakarima, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Work company of singing threshers at Sanasi’s farm, Kakarima, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Limba women pounding rice, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

‘Funky Freddy’ of The Jungle Leaders playing hip-hop political songs that were banned from Radio Sierra Leone for their protest lyrics (courtesy Karin Barber). | |

‘The Most Wonderful Mende Musician with his Accordion’: Mr Salla Koroma, Sierra Leone. | |

Radio. Topical and political songs, already strong in Africa, receive yet further encouragement by the ubiquitous presence of local radio (courtesy of Morag Grant). | |

Sites of many Limba fictional narratives a) entrance to a hill top Limba village, Kakarima 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan); b) start of the bush and the bush paths where wild beasts and the devils of story roam free, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

‘Great Zimbabwe’, the spectacular ruins in the south of the modern Zimbabwe, 1964 (photo David Murray). | |

‘Karanke Dema, master story-teller, drummer, musician and smith, Kakarima, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Thronged Limba law court, site of oratory, Kamaba, 1961 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Masked Limba dancer and supporters, Kakarima, 1962 (photo Ruth Finnegan). | |

Dancing in Freetown—continuing site of oral literature and its practitioners, 1964 (photo David Murray). | |

At end: Maps of Africa (© John Hunt). |

Figure 1. Dancer, West Africa (photo Sandra Bornand).

Foreword

Mark Turin

The study and appreciation of oral literature is more important than ever for understanding the complexity of human cognition.

For many people around the world—particularly in areas where history and traditions are still conveyed more through speech than in writing—the transmission of oral literature from one generation to the next lies at the heart of culture and memory. Very often, local languages act as vehicles for the transmission of unique forms of cultural knowledge. Oral traditions that are encoded in these speech forms can become threatened when elders die or when livelihoods are disrupted. Such creative works of oral literature are increasingly endangered as globalisation and rapid socio-economic change exert ever more complex pressures on smaller communities, often challenging traditional knowledge practices.

It was in order to nurture such oral creativity that the World Oral Literature Project was established at the University of Cambridge in 2009. Affiliated to the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the project has been co-located at Yale University since 2011.

As an urgent global initiative to document and disseminate endangered oral literatures before they disappear without record, the World Oral Literature Project works with researchers and local communities to document their own oral narratives, and aspires to become a permanent centre for the appreciation and preservation of all forms of oral culture. Through the project, our small team provides modest fieldwork grants to fund the collecting of oral literature, and we run training workshops for grant recipients and other scholars to share their experiences and methodologies. Alongside a series of published occasional papers and lectures—all available for free from our website—project staff have helped

to make over 30 collections of oral literature (from five continents and dating from the 1940s to the present) accessible through new media platforms online.

1

In supporting the documentation of endangered oral literature and by building an online network for cooperation and collaboration across the disciplines, the World Oral Literature Project now nurtures a growing community of committed scholars and indigenous researchers across the globe.

The beautifully produced and fully revised new edition of Ruth Finnegan’s classic

Oral Literature in Africa

is a perfect illustration of the sort of partnership that the World Oral Literature Project has sought to promote. In this triangulation between a prominent scholar and her timeless work, an innovative and responsive publisher and a small but dynamic research project, we have leveraged digital technologies to offer global access to scholarly knowledge that had been locked away, out of print for decades, for want of a distribution platform.

Much has changed in the world since Finnegan handed in her original typed manuscript to the editors at Clarendon Press in Oxford in 1969. The most profound transformation is arguably the penetration of, and access to technology. In the decades that followed the publication of her instantly celebrated book, computers developed from expensive room-sized mainframes exclusively located in centres of research in the Western hemisphere, into cheap, portable, consumer devices—almost disposable and certainly omnipresent. It seemed paradoxical that with all of the world’s knowledge just a few keystrokes away, thanks to powerful search engines and online repositories of digitised learning, a work of such impact and consequence as

Oral Literature in Africa

could be said to be ‘out of print’. The World Oral Literature Project embarked on its collaboration with Open Book Publishers in order to address this issue, and to ensure that Finnegan’s monograph be available to a global audience, once and for all.

Finnegan was patient as we sought the relevant permissions for a new edition, and then painstakingly transformed her original publication, through a process of scanning and rekeying (assisted and frustrated in equal measure by the affordance of optical character recognition) into the digital document that it is today. At this point, thanks are due to Claire Wheeler and Eleanor Wilkinson, both Research Assistants at the World Oral Literature Project in Cambridge, whose care and precision is reflected

in the edition that you are now reading. In addition, through the online Collections Portal maintained by our project, we have given new life to Finnegan’s audio and visual collection in a manner that was unimaginable when she made the original recordings during her fieldwork in the 1960s. The digital collection can be explored online at

www.oralliterature.org/OLA

, and I encourage you to visit the site to experience for yourself the performative power of African oral literature.

2

In the Preface to the first edition, Finnegan writes that she found to her ‘surprise that there was no easily accessible work’ on oral literature in general, a realisation which spurred her on to write the monograph that would become

Oral Literature in Africa

. This re-edition of her work gives new meaning to the phrase ‘easily accessible’; not only does the author demonstrate her clarity of insight through her engaging writing style, but this version will be read, consumed and browsed on tablets, smart phones and laptops, in trains, planes and buses, and through tools that are as yet unnamed and uninvented.

The impact and effectiveness of digital editions, then, lies in the fact that they are inherently more democratic, challenging the hegemony of traditional publishers and breaking down distribution models that had been erected on regional lines. While the digital divide is a modern reality, it is not configured on the basis of former coloniser versus former colonised, or West-versus-the-Rest, but primarily located within individual nations, both wealthy and poor. Now, for the first time,

Oral Literature in Africa

is available to a digitally literate readership across the world, accessible to an audience whose access to traditional print editions published and disseminated from Europe remains limited. Digital and mobile access is particularly relevant for Africa, where smart phone penetration and cell coverage is encouragingly high.

While it is beyond doubt that technology has transformed access to scholarly information and the landscape of academic publishing, questions remain about long-term digital preservation and the endurance of web-based media. In a world of bits and bytes, what (if anything) can be counted as permanent? Is there not something to be said for a traditional printed artefact for the inevitable day when all the servers go down? Our partners, the Cambridge-based Open Book Publishers, have developed an elegant hybrid approach straddling the worlds of web and print: free, global,

online access to complete digital editions of all publications alongside high quality paperback and hardback editions at reasonable prices, printed on demand, and sent anywhere that a package can be delivered. This is academic publishing 2.0: connecting a global readership with premium knowledge and research of the highest quality, no matter where they are and how far away the nearest library is.

Orality is often, but not always, open. Orality is also public, both in its production, display and in its eventual consumption. It is fitting that the ‘update’ of Ruth Finnegan’s essentially un-updateable text has been digitally reborn, open to all, as relevant today as it was when it was first published, and serves as the first volume of our new World Oral Literature Series.

New Haven, Connecticut, May 2012

Footnotes

1

To view our series of occasional papers, lectures and online collections, please visit <

http://www.oralliterature.org/

>.

2

For a video interview with Ruth Finnegan conducted by Alan Macfarlane in January 2008, please visit <

www.sms.cam.ac.uk/media/1116447

>.

Figure 2. The author on fieldwork in Limba country, northern Sierra Leone, 1964.