Orphan #8 (43 page)

Authors: Kim van Alkemade

Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at

hc.com

.

The True Stories That Inspired

Orphan #8

Motion to Purchase Wigs Approved

In July 2007, I was doing family research at the Center for Jewish History in New York City, sifting through some materials I’d requested from the American Jewish Historical Society archives. The idea of writing a historical novel was the furthest thing from my mind when I opened Box 54 of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum collection and began leafing through the meeting minutes of the Executive Committee.

The minutes gave intimate glimpses into the day-to-day operations of an orphanage that, in the 1920s, was one of the largest child care institutions in the country, housing over 1,200 children in its massive building on Amsterdam Avenue. On October 9, 1921, the Committee authorized $200 (over $2,000 in today’s dollars)

to costume children for the “Pageant on Americanization.” The question of band instruments demanded much of the Executive Committee’s attention: in October 1922, the decision to change from high- to low-pitched instruments was deferred; in April 1923, $3,500 was approved to equip the band with low-pitched instruments; in January 1926, the theft of the new band instruments was reported to the Board. Syphilis was a concern, too, with the Committee instructing the superintendent in January 1923 to work with the physician regarding syphilitic cases; by October 1926, nineteen cases of syphilis were diagnosed in the orphanage, fourteen of them in girls.

The Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by the real Hebrew Orphan Asylum in Manhattan. Dedicated in 1884, it occupied two city blocks until it was demolished in the 1950s. It is now the site of the Jacob Schiff Playground

. Photograph from author’s collection.

But it was a motion made on May 16, 1920, that caught my eye and became the inspiration for

Orphan #8

. On that day, the Committee approved the purchase of wigs for eight children who

had developed alopecia as a result of X-ray treatments given to them at the Home for Hebrew Infants by a Dr. Elsie Fox, a graduate of Cornell Medical School. Questions cascaded through my mind. Who was this woman administering X-rays? Why did the orphanage have an X-ray machine, and what were the children being treated for? What might have happened to one of these bald children after she had grown up in the orphanage? How would this have influenced the course of her life?

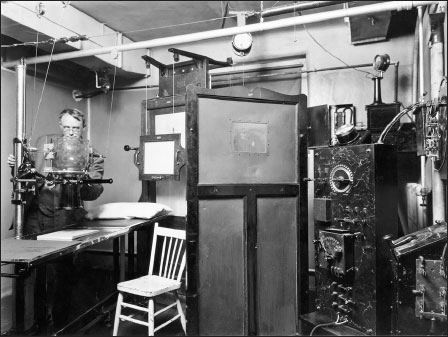

My description of the X-ray room at the Hebrew Infant Home was inspired by this 1919 photograph of the X-ray room at Vancouver General Hospital—where no medical research involving children was conducted

. Courtesy of Vancouver Coastal Health.

I remembered then a story my great-grandmother, Fannie Berger, used to tell about her time working as Reception House counselor in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. She’d been hired by the superintendent in January 1918 when she went to the orphanage to commit her sons to the institution after her husband had absconded. One of Fannie’s jobs was to shave the heads of newly admitted children as a precaution against lice. It was a task she disliked, but refused only once.

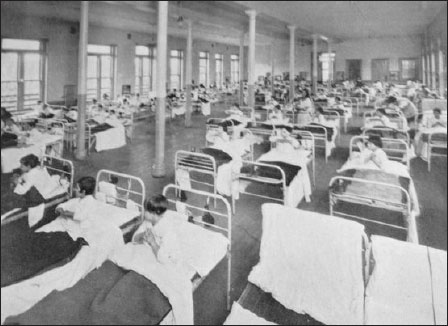

Rachel’s dormitory in the Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by this photograph of a dormitory in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum

. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library.

We used to drive out to Brooklyn when I was little, my mom and dad and brother and I, to visit my Grandma Fannie. We’d often find her on a bench outside her building, chatting with other old ladies. Up in her tiny apartment we’d perch uncomfortably on the day bed while we visited—I can’t imagine, now, a child with the patience for such an afternoon. I remember Fannie telling a story about the time a girl with beautiful hair was committed to the orphanage. It may be my imagination rather than my memory that makes this particular head of hair so remarkably red. Fannie was so taken with this girl’s hair that she refused to shave it off, took her request all the way up to the superintendent, who finally gave permission. In my Grandma Fannie’s telling, it was a singular moment of bravery, her refusal to shave this one girl’s head of hair.

At the Center for Jewish History, reading about the children who had been given X-ray treatments at the Hebrew Infant Asylum, I

wondered what if these bald children were in my great-grandmother’s care when this other girl came into Reception, the girl with hair so magnificent Fannie would challenge authority to preserve it? I imagined the contrast between these two girls escalating into a rivalry, the hair itself becoming their battleground. That was the moment Rachel and Amelia were created, and with their inception the idea for a novel began to emerge.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum baseball team, circa 1920. My grandfather, Victor, is seated in front of his brother Seymour, the team’s “pillar of strength.”

Photograph from author’s collection.

Contractor of Waists

There is some mystery to the disappearance of my great-grandfather, Harry Berger, a contractor in the shirtwaist industry who’d been born in Russia in 1884 and arrived in New York in 1890. On the admission form to the orphanage, it is remarked that “Father is tubercular and is at present in Colorado with his brother,” which gives the impression that illness and the inability to work were behind Harry’s decision to leave his wife and three young sons. But the story I remember hearing is that Harry had gotten a young Italian woman who worked for him pregnant; when her family threatened to kick her out, Harry asked his wife

if the girl could live with them. Fannie refused, but she hadn’t been prepared for Harry to up and leave. Decades later, suffering from dementia, Fannie relived the day he left, pleading from her nursing home bed to the ghost of her husband: “Don’t leave, Harry. Think of the boys. Put back the suitcase, we’ll get through this.”

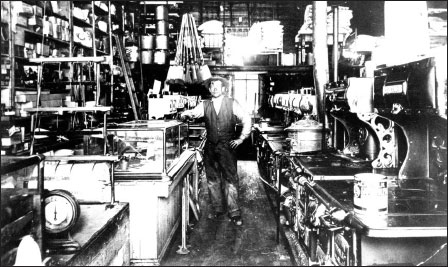

I imagined Rabinowitz Dry Goods to look much like Isaacs Hardware Store in Leadville, Colorado

. Courtesy of the Beck Archives, Special Collections, University Libraries, University of Denver.

They didn’t get through it. Harry ran off to Leadville, Colorado. Fannie couldn’t go home to her parents because she’d defied her father in marrying Harry—unlike Fannie’s obedient sister, who’d been married off by their father to a rich uncle. After Harry left, Fannie sold her household effects for a total of $60. She might have turned, in desperation, to prostitution—many abandoned mothers occasionally did—or tried to eke out an existence on charity. Instead, she went to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, like thousands of parents before her, who, for reasons of death or desertion or illness, were unable to care for their children.

The Hebrew Infant Home, where Dr. Solomon conducted her research, was inspired by the real Hebrew Infant Asylum. This picture shows the glassed-in babies in the isolation ward

. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library.

Like many inmates of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, my grandfather Victor and his brothers, Charles and Seymour, were not really orphans, and certainly not up for adoption. What was unusual was that their mother ended up living at the institution to which she had committed them. In 1918, the orphanage was experiencing a serious shortage of help. With so many men in the military, women had greater employment opportunities, making jobs at the orphanage—with its low wages, long hours, and residence requirements—a hard sell. While Fannie always said it was a miracle that the superintendent offered her a position on the very day her sons were admitted to the institution, it’s also true that her poverty and desperation to be near her children made her an ideal candidate.

When Fannie started working at the orphanage as a domestic in the Reception House, Charles was only three years old—too young for the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. He was sent to the Hebrew Infant Asylum, where he soon contracted measles. When Fannie went to visit him, she wasn’t allowed into the ward and could only stand in the hallway listening to his cries. When Charles recovered, Fannie threatened to quit unless her son was allowed to live with her in the Reception House. After Charles was old enough to join his brothers in the main building, Fannie was promoted to counselor and her duties included helping to process new admissions. Every child committed to the orphanage spent weeks quarantined in Reception. Besides having their heads shaved, they were evaluated by a doctor for physical and mental condition, tested for diphtheria, vaccinated and given an eye test, a dental exam, and surgery to remove their tonsils and adenoids. My great-grandmother Fannie often let the traumatized children cry themselves to sleep at night in her arms.

Ever Efficient Boy of the Home

Even before my discoveries at the Center for Jewish History, I’d wanted to learn all I could about the institution where my grandfather Victor had grown up—an institution so large it was its own census district. I’d read

The Luckiest Orphans

, the most complete history of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum ever written, and was so appreciative of the insight it gave me into my

grandfather’s childhood that I wrote the author, Hyman Bogan, a letter of thanks. Apparently, he wasn’t used to getting fan mail. I was amazed when I answered my phone one evening in 2001 to hear a strange man’s voice say, “Is this Kim? You wrote to me about my buh-buh-buh-book.” Hy later told me his stutter had begun after being slapped on his first day in the orphanage.