Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show (16 page)

Read Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show Online

Authors: Edmund R. Schubert

Father’s hands were bound together behind his back, but now one of the soldiers loosed them and he reached out to Tzu. Tzu ran to him and hugged him. “Are you under arrest?” asked Tzu. He had seen arrests on the vids.

“Yes,” said Father.

“Is it because of the answers?” asked Tzu. It was the only thing he could think of that his father had ever done wrong.

“Yes,” said Father.

Tzu pulled away from him and faced the man from the tests. “But it was all right,” said Tzu. “I didn’t use those answers.”

“I know you didn’t,” said the man.

“What?” said Father.

Tzu turned around to face him. “I didn’t like it that you were only going to pretend I was best child. So I didn’t use any of the answers. I didn’t want to be called best child if I wasn’t really.” He turned back to the man from the fleet. “Why are you arresting him when I didn’t use the answers?”

The man smiled confidently. “It doesn’t matter whether you used them or not. What matters is that he obtained them.”

“I’m sorry,” said Father. “But if my son did not answer the questions correctly, how can you prove that any cheating took place?”

“For one thing, we’ve been recording this entire interview,” said the man from the fleet. “The fact that he knew he had been given the right answers and chose to answer incorrectly does not change the fact that you trained him to take the test.”

“Maybe what you need is a little better security with the answers,” said Father angrily.

“Sir,” said the man from the fleet, “we always allow people to buy the test if they try to get it. Then we watch and see what they do with it. A child as bright as this one could not possibly have answered every question wrong unless he absolutely had the entire test down cold.”

“I got the first three right,” said Tzu.

“Yes, all but three were wrong,” said the man from the fleet. “Even children of very limited intellect get some of them right by random chance.”

Father’s demeanor changed again. “The blame is entirely mine,” he said. “The boy’s mother had no idea I was doing this.”

“We’re quite aware of that. She will not be bothered, except of course to inform her. The penalty is not severe, sir, but you will certainly be convicted and serve the days in prison. The fleet makes no exceptions for anyone. We need to make a public example of those who try to cheat.”

“Why, if you let them cheat whenever they want?” said Father bitterly.

“If we didn’t let people buy the answers, they might figure out much cleverer ways to cheat the test. Ways we wouldn’t necessarily catch.”

“Aren’t you smart.”

Father was being sarcastic, but Tzu thought they

were

smart. He wished he had thought of that.

“Father,” said Tzu. “I’m sorry about Yuan Shikai.”

Father glanced furtively toward the soldiers. “Don’t worry about that,” he said.

“But I was thinking. It’s been so many hundred years since Yuan Shikai lived that he must have

hundreds

of descendants now. Maybe thousands. It doesn’t have to be me, does it? It could be one of

them

.”

“Only you,” said Father softly. He kissed him good-bye. They bound his wrists behind his back and led him out of the house.

The woman from the test stayed with Tzu and kept him from following to watch them take Father away. “Where will they take him?” asked Tzu.

“Not far,” said the woman. “He won’t be imprisoned for very long, and he’ll be quite comfortable there.”

“But he’ll be ashamed,” said Tzu.

“For a man with so much pride in his family,” said the woman, “that is the harshest penalty.”

“I should have answered most of the questions right,” said Tzu. “It’s my fault.”

“It’s not your fault,” said the woman. “You’re only a child.”

“I’m almost six,” said Tzu.

“Besides,” said the woman, “we watched Guo-rong coaching you. Teaching you the test.”

“How?” asked Tzu.

She tapped the little monitor on the back of his neck.

“Father said that was just to keep me safe. To make sure my heart was beating and I didn’t get lost.”

“Everything your eyes see,” said the woman, “we see. Everything you hear, we hear.”

“You lied, then,” said Tzu. “You cheated, too.”

“Yes,” said the woman. “But we’re fighting a war. We’re allowed to.”

“It must have been boring, watching everything I see. I never get to see

anything

.”

“Until last night,” she said.

He nodded.

“So many people on the streets,” she said. “More than you can count.”

“I didn’t try to count them,” said Tzu. “They were going all different directions and in and out of buildings and up and down the side streets. I stopped after three thousand.”

“You counted three thousand?”

“I’m always counting,” said Tzu. “I mean my counter is.”

“Your counter?”

“In my head. It counts everything and tells me the number when I need it.”

“Ah,” she said. She took his hand. “Let’s go back to your room and take another test.”

“Why?”

“

This

test you don’t know the answers to.”

“I bet I do,” said Tzu. “I bet I figure them out.”

“Ah,” said the woman. “A different kind of pride.”

Tzu sat down and waited for her to set up the test.

Afterword by Orson Scott Card

Smart kids fascinate me, because even when they function at genius levels, there are still things they don’t know. Intelligence is about capacity; sophistication is about experience and knowledge and understanding of context.

Knowing that having a child chosen for Battle School would be a matter of very high prestige, I realized that it is inevitable that someone would cheat. How would Battle School deal with this? Was it possible for anyone to beat the system? I decided not—especially when they had the option of installing monitors to watch the genius children all the time.

Or perhaps the monitors were installed

because

of cheaters, to make sure that the children who did well were the real thing.

Anyway, once I realized that the testers from Battle School would have a system in place to trap cheaters and deal with them, I then tried to imagine how a genius child might react to his parents’ assumption that he would need to cheat in order to get into Battle School.

That’s when I decided that Han Tzu—Hot Soup—was going to be the kid who had to deal with his father’s lack of confidence in him.

Then the problem became one of deciding what life would be like in China more than a century in the future. Of course, predicting the future is not what sci-fi writers are good at. Heinlein outlived large swaths of his “future history,” and even though there’s zero chance I’ll outlive mine, it’s still annoying when things happen that make little details in a story wrong.

Still, there are continuities in Chinese culture that transcend the politics of history. I hope I gave Han Tzu a world that rings true, now and in years to come.

BY

T

IM

P

RATT

The Stolen

State, The Magpie City, The Nex, The Ax—this is the place where I live, and hover, and chafe in my service; the place where I take my small bodiless pleasures where I may. Nexington-on-Axis is the proper name, the one the Regent uses in his infrequent public addresses, but most of the residents call it other things, and my—prisoner? partner? charge? trust?—my associate, Howlaa Moor, calls it The Cage, at least when zie is feeling sorry for zimself.

The day the fat man began his killing spree, I woke early, while Howlaa slept on, in a human form that snored. I looked down on the streets of our neighborhood, home to low-level government servants and the wretchedly poor. The sky was bleak, and rain filled the potholes. The royal orphans had snatched a storm from somewhere, which was good, as the district’s roof gardens needed rain.

I saw a messenger approach through the cratered street. I didn’t recognize his species—he was bipedal, with a tail, and his skin glistened like a salamander’s, though his gait was bird-like—but I recognized the red plume jutting from his headband, which allowed him to go unmolested through this rough quarter.

“Howlaa,” I said. “Wake. A messenger approaches.”

Howlaa stirred on the heaped bedding, furs and silks piled indiscriminately with burlap and canvas and even coarser fabrics, because Howlaa’s kind enjoy having as much tactile variety as possible. And, I suspect, because Howlaa likes to taunt me with reminders of the physical sensations I cannot experience.

“Shushit, Wisp,” Howlaa said. My name is not Wisp, but that is what zie calls me, and I have long since given up on changing the habit. “The messenger could be coming for anyone. There are four score civil servants on this block alone. Let me sleep.” Howlaa picked up a piece of half-eaten globe-fruit and hurled it at me. It passed through me without effect, of course, but it annoyed me, which was Howlaa’s intent.

“The messenger has a red plume, skinshifter,” I said, making my voice resonate, making it creep and rattle in tissues and bones, so sleep or shutting-me-out would be impossible.

“Ah. Blood business, then.” Howlaa threw off furs, rose, and stretched, arms growing more joints and bends as zie moved, unfolding like origami in flesh. I could not help a little subvocal gasp of wonder as zir skin rippled and shifted and settled into Howlaa’s chosen morning shape. I have no body, and am filled with wonder at Howlaa’s mastery of physical form.

Howlaa settled into the form of a male Nagalinda, a biped with long limbs, a broad face with opalescent eyes, and a lipless mouth full of triangular teeth. Nagalinda are fearsome creatures with a reputation for viciousness, though I have found them no more uniformly monstrous than any other species; their cultural penchant for devouring their enemies has earned them a certain amount of notoriety even in the Ax, though. Howlaa liked to take on such forms to terrify government messengers if zie could. Such behavior was insubordinate, but it was such a small rebellion that the Regent didn’t even bother to reprimand Howlaa for it—and having such willfully rude behavior so completely disregarded only served to annoy Howlaa further.

The Regent knew how to control us, which levers to tug and which leads to jerk, which is why he was the Regent, and we were in his employ. I often think the Regent controls the city as skillfully as Howlaa controls zir own form, and it is a pretty analogy, for the Ax is almost as mutable as Howlaa’s body.

The buzzer buzzed. “Why don’t you get that?” Howlaa said, grinning. “Oh, yes, right, no hands, makes opening the door tricky. I’ll get it, then.”

Howlaa opened the door to the messenger, who didn’t find the Nagalinda form especially terrifying. The messenger was too frightened of the fat man and the Regent to spare any fear for Howlaa.

I floated.

Howlaa ambled. The messenger hurried ahead, hurried back, hurried ahead again, like an anxious pet. Howlaa could not be rushed, and I went at the pace Howlaa chose, of necessity, but I sympathized with the messenger’s discomfort. Being bound so closely to the Regent’s will made even tardiness cause for bone-deep anxiety.

“He’s a fat human, with no shirt on, carrying a giant battle-ax, and he chopped up a brace of Beetleboys armed with dung-muskets?” Howlaa’s voice was blandly curious, but I knew zie was incredulous, just as I was.

“So the messenger reports,” I said.

“And then he disappeared, in full view of everyone in Moth Moon Market?”

“Why do you repeat things?” I asked.

“I just wondered if it would sound more plausible coming from my own mouth. But even my vast reserves of personal conviction fail to lend the story weight. Perhaps the Regent made it all up, and plans to execute me when I arrive.” Howlaa sounded almost hopeful. “Would you tell me, little Wisp, if that were his plan?”

Howlaa imagines I have a closer relationship with the Regent than I do, and has always believed I willingly became a civil servant. Howlaa does not know I am bound to community service for my past crimes, just as Howlaa is, and I allow this misconception because it allows me to act superior and, on occasion, even condescend, which is one of the small pleasures available to us bodiless ones. “I think you are still too valuable and tractable for the Regent to kill,” I said.

“Perhaps. But I find the whole tale rather unlikely.”

Howlaa walked along with zir mouth open, letting the rain fall into zir mouth, tasting the weather of other worlds, looking at the clouds.

I looked everywhere at once, because it is my duty and burden to look, and record, and, when called upon, to bear witness. I never sleep, but every day I go into a small dark closet and look at the darkness for hours, to escape my own senses. So I saw everything in the streets we passed, for the thousandth time, and though details were changed, the essential nature of the neighborhood was the same. The buildings were mostly brute and functional, structures stolen from dockyards, ghettos, and public housing projects, taken from the worst parts of the thousand thousand worlds that grind around and above Nexington-on-Axis in the complicated gearwork that supports the structure of all the universes. We live in the pivot, and all times and places turn past us eventually, and we residents of the Ax grab what we can from those worlds in the moment of their passing—and so our city grows, and our traders trade, and our government prospers. It is kleptocracy on a grand scale.

But sometimes we grasp too hastily, and the great snatch-engines tended by the Regent’s brood of royal orphans become overzealous in their cross-dimensional thieving, and we take things we didn’t want after all, things the other worlds must be glad to have lost. Unfortunate imports of that sort can be a problem, because they sometimes disrupt the profitable chaos of the city, which the Regent cannot allow. Solving such problems is Howlaa’s job.

We passed out of our neighborhood into a more flamboyant one, filled with emptied crypts, tombs, and other oddments of necropoli, from chipped marble angels to fragments of ornamental wrought iron. To counteract this funereal air, the residents had decorated their few square blocks as brightly and ostentatiously as possible, so that great papier-mâché birds clung to railings, and tombs were painted yellow and red and blue. In the central plaza, where the pavement was made of ancient headstones laid flat, a midday market was well under way. The pale vendors sold the usual trinkets, obtained with privately owned low-yield snatch-engines, along with the district’s sole specialty, the exotic mushrooms grown in cadaver-earth deep in the underground catacombs. Citizens shied away from the red-plumed messenger, bearer of bloody news, and shied farther away at the sight of Howlaa, because Nagalinda seldom strayed from their own part of the city, except on errands of menace.

As we neared the edge of the plaza there was a great crack and whoosh, and a wind whipped through the square, eddying the weakly linked charged particles that made up my barely physical form.

A naked man appeared in the center of the square. He did not rise from a hidden trapdoor, did not drop from a passing airship, did not slip in from an adjoining alley. Anyone else might have thought he’d arrived by such an avenue, but I see in all directions, to the limits of vision, and the man was simply there.

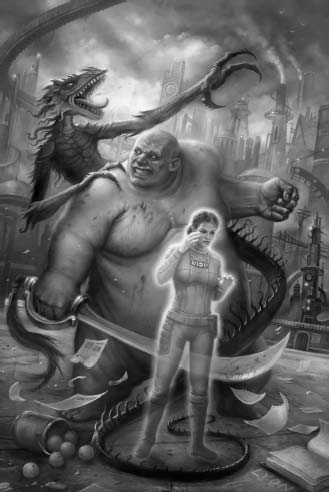

Such magics were not unheard of, but they were never associated with someone like this. He appeared human, about six feet tall, bare-chested and obese, pale skin smeared with blood. He was bald, and his features were brutish, almost like a child’s clay figure of a man.

He held an absurd sword in his right hand, the blade as long as he was tall, but curved like a scimitar in a theatrical production about air-pirates, and it appeared to be made of gold, an impractical metal for weaponry. When he smiled, his lips peeled back to show an amazing array of yellow stump-teeth. He reared back his right arm and swung the sword, striking a merrow-woman swaddled all over in wet towels, nearly severing her arm. The square plunged into chaos, with vendors, customers, and passersby screaming and fleeing in all directions, while the fat man kept swinging his sword, moving no more than a step or two in any direction, chopping people down as they ran.

“The reports were accurate after all,” Howlaa said. “I’ll go sort this.” The messenger stood behind us, whimpering, tugging at Howlaa’s arm, trying to get zim to leave.

“No,” I said. “We were ordered to report to the Regent, and that’s what we’ll do.”

Howlaa spoke with exaggerated patience. “The Regent will only tell me to find and kill this man. Why not spare myself the walk, and kill him now? Or do you think the Regent would prefer that I let him kill more of the city’s residents?”

We both knew the Regent was uninterested in the well-being of individual citizens—more residents were just a snatch-and-grab away, after all—but I could tell Howlaa would not be swayed. I considered invoking my sole real power over Howlaa, but I was under orders to take that extreme step only in the event that Howlaa tried to escape the Ax or harm one of the royal orphans. “I do not condone this,” I said.

“I don’t care.” Howlaa strode into the still-flurrying mass of people. In a few moments zie was within range of the fat man’s swinging sword. Howlaa ducked under the man’s wild swings and reached up with a long arm to grab his wrist. By now most of the people able to escape the square had done so, and I had a clear view of the action.

The fat man looked down at Howlaa as if zie were a minor annoyance, then shook his arm as if to displace a biting fly.

Howlaa flew through the air and struck a red-and-white-striped crypt headfirst, landing in a heap.

The fat man caught sight of the messenger—who was now rather pointlessly trying to cower behind me—and sauntered over. The fat man was extraordinarily bowlegged, his chest hair was gray, and his genitals were entirely hidden under the generous flop of his belly-rolls.

As always in these situations, I wondered what it would be like to fear for my physical existence, and regretted that I would never know.

Behind the fat man, Howlaa rose, rippled, and transformed, taking on zir most fearsome shape, a creature I had never otherwise encountered, that Howlaa called a Rendigo. It was reptilian, armored in sharpened bony plates, with a long snout reminiscent of the were-crocodiles that lived in the sewer labyrinths below the Regent’s palace. The Rendigo’s four arms were useless for anything but killing, paws gauntleted in razor scales, with claws that dripped blinding toxins, and its four legs were capable of great speed and leaps. Howlaa seldom resorted to this form, because it came with a heavy freight of biochemical killing rage that could be hard to shake off afterward. Howlaa leapt at the fat man, landing on his back with unimaginable force, poison-wet claws flashing.

The fat man swiveled at the waist and flung Howlaa off his back, not even breaking stride, raising his sword over the messenger. The fat man was uninjured; all the blood and nastiness that streaked his body came from his victims. His sword passed through me and cleaved the messenger nearly in two.

The fat man smiled, looking at his work, then frowned, and blinked. His body flickered, becoming transparent in places, and he moaned before disappearing.

Howlaa, back in Nagalinda form, crouched and vomited out a sizzling stream of Rendigo venom and biochemical rage-agents.

Howlaa wiped zir mouth, then stood up, glancing at the dead messenger. “Let’s try it your way, Wisp. On to the Regent’s palace. Perhaps he has an idea for…another approach to the problem.”

I thought about saying “I told you so.” I couldn’t think of any reason to refrain. “I told you so,” I said.

“Shushit,” Howlaa said, preoccupied, thinking, doing what zie did best, assessing complex problems and trying to figure out the easiest way to kill the source of those problems, so I let zim be, and didn’t taunt further.

Before we

entered the palace, Howlaa took on one of zir common working shapes, that of a human woman with a trim assassin-athlete’s body, short dark hair, and deceptively innocent-looking brown eyes. The Regent—who had begun his life as human, though long contact with the royal orphans had wrought certain changes in him physiologically and otherwise—found this form attractive, as I had often sensed from fluctuations in his body heat. I’d made the mistake of sharing that information with Howlaa once, and now Howlaa wore this shape every time we met with the Regent, in hopes of discomforting him. I thought it was a wasted effort, as the Regent simply looked, and enjoyed, and was untroubled by Howlaa’s unavailability.

We went up the cloudy white stone steps of the palace, which had been a great king’s residence in some world far away, and was unlike any other architecture in Nexington-on-Axis. Some said the palace was alive, a growing thing, which seemed borne out by the ever-shifting arrangement of minarets and spires, the way the hallways meandered organically, and walls that appeared and disappeared. Others said it was not alive but simply magical. I had been reliably informed that the palace, unable to grow out because of the press of other government buildings on all sides, was growing down, adding a new sub-basement every five years or so. No one knew where the excavated dirt went, or where the building materials came from—no one, that is, except possibly the royal orphans, who were not likely to share the knowledge with anyone.