Out of Control

Authors: Richard Reece

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Text copyright © 2012 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

Â

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansâelectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseâwithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Â

Darby Creek

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North Minneapolis,

MN 55401 U.S.A.

Â

Website address:

www.lernerbooks.com

Â

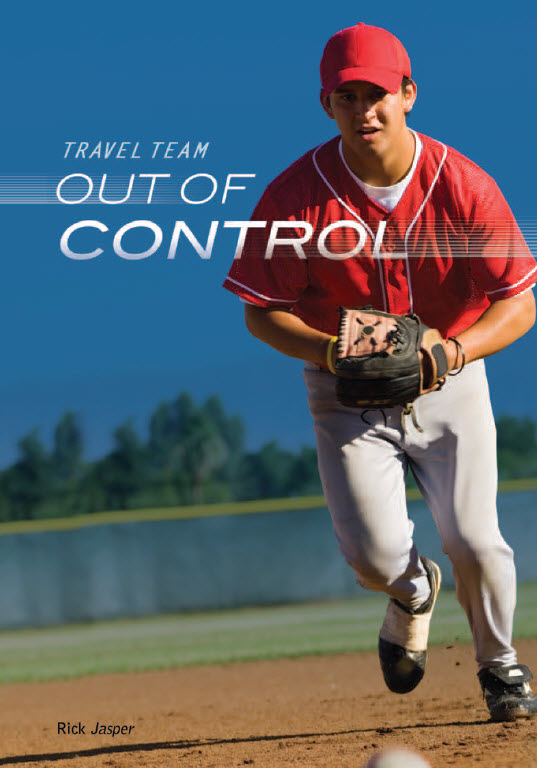

The images in this book are used with the permission of: © Kelpfish/Dreamstime.com, p. 109; © iStockphoto.com/Jill Fromer, p. 112 (banner background); © iStockphoto.com/Naphtalina, pp. 112, 113, 114 (brick wall background). Front Cover: moodboard/CORBIS. Back Cover: © Kelpfish/Dreamstime.com.

Â

Main body text set in Janson Text 12/17.5.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Â

Jasper, Rick, 1948â

Out of control / by Rick Jasper.

p. cm. â(Travel team)

ISBN 978â0â7613â8323â9 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper)

[1. BaseballâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.J32Ou 2012

[Fic]âdc23

2011027948

Â

Manufactured in the United States of America

1âBPâ12/31/11

Â

eISBN: 978-0-7613-8733-6 (pdf)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-3059-4 (ePub)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-3060-0 (mobi)

Â

Â

Â

Â

TO MY GRANDMOTHER, WHO

BOUGHT ME MY FIRST GLOVE

Â

Â

Â

Â

“ The way a team plays as a whole

determines its success. You may have the

greatest bunch of individual stars in the

world, but if they don't play together, the

club won't be worth a dime.”

Â

â

BABE RUTH

CHAPTER

1

I

f you had attended the baseball game between the Las Vegas Roadrunners and the Boise Bulls on that steamy June afternoon, you would have seen something unusual. Both summer travel teams were at the elite level, which is to say that both teams had teenage players under seventeen years old with college or even professional potential. But that afternoon you would have seen something that looked more like a scene from a Little League game.

It began simply enough. The Roadrunners were down by two in the bottom of the eighth inning. Thanks to a walk, they had a runner on first with nobody out: their shortstop, Carlos “Trip” Costas. Trip was speedy, so the expectation was that he would try to steal second, and indeed he was taking a generous enough lead to draw the attention of the pitcher.

The Bulls' pitcher was good enough, or well-coached enough, to expect the steal. But even if he had been unaware, the screaming of one of the Roadrunners' fans would have alerted him.

“STEAL! STEAL, CARLOS! Jeez, move your butt! This guy's got nothing!”

A few people in the crowd looked around, but most of the Roadrunners' faithful knew without looking that the screamer was Trip's father, Julio. Like Trip, they ignored him.

The game slowed down considerably with the next batter, center fielder Danny Manuel. He was a good match for the pitcher; both of them wereâto put it nicely in a word often used by sports broadcastersâ“deliberate.” They took their time. The pitcher would fool around with the resin bag, make a couple of throws to first, fool around with his cap, and then again go to the resin bag. Once he was finally ready to pitch, Danny would call time and step out of the batter's box.

When a pitch actually managed to occur, Danny would foul it off. The afternoon was warm, the sun was bright, and the sky was a monotonous, cloudless, desert blue. What should have been a tense situation was becoming nap-inducing.

Julio was still awake, though. He was still yelling for the steal. And he was still being ignored, as the attention of the other fans and, as it turned out, some of the players waned. The count drowsed its way to 2â2, and Danny kept fouling off pitchesâover the backstop, tipped into the dirt, down the line, high, low. It was after about seven of these that the Bulls' catcher noticed Trip's overlong lead.

The next pitch was outside, on the first-base side of the plate. The catcher gunned it to first and Trip, as he admitted later, was caught napping. The first baseman tagged him out, the Roadrunners' fans groaned, and Trip headed back to the dugout.

From the seats came an outraged bellow, and suddenly Julio was on the field, heading for his son. What transpired looked like a coach-umpire altercation, with Julio in the role of coach, cursing in Spanish and waving his arms, while Trip stared at him with little expression while trying to walk away. That's when the shoving started. Julio grabbed the teenager by the shoulder and started shaking him. Trip was four inches taller and pushed his dad away, but Julio kept grabbing him and getting in his face.

“What were you thinking? You had that guy! You could steal standing up!”

Finally, Trip started backing his dad up, shoving the heels of his hands against Julio's chest.

Before things got really ugly, the umpires converged on the two and the Roadrunners' bench emptied. The resulting spectacle consisted of a baseball team separating father from son, handing Julio over to security and shielding Trip as they ushered him to the dugout. Trip hadn't said anything to that point, but as his dad was escorted out he turned and yelled, in a voice as impressively loud as Julio's, “Happy freakin' Father's Day!”

When the game finally resumed, Danny flied out. Zack Waddell singled, but he was then thrown out on Nick Cosimo's subsequent grounder. The Roadrunners went quietly in the ninth and lost by two. But by then the game itself seemed like a sideshow to the main event. When people left the field that night they were talking not about who won or lost, but about crazy Julio Costas.

My father.

CHAPTER

2

Y

es, my dad is the Julio Costas. Your parents probably have some of his records. Maybe they've even seen him perform in Vegas, where he pretty much stays now except for when he has TV appearances and recording sessions. He never liked touring, and now he doesn't need to.

Here's a description from Wikipedia:

Julio Costas is a Venezuelan singer who has sold over 200 million records worldwide in fourteen languages. He has released forty albums and is one of the top twenty best-selling musical artists in history. He became internationally known in the early '80s as a performer of romantic ballads.

His story is more interesting than that, and he's very fond of telling it, so I know it by heart. Dad was born in the La Dolorita barrio of Caracas. He took me and my brothers on a trip to Caracas once, but we didn't go near La Dolorita. It would have been too dangerous. The dream of the people who live in its violence and dirt is to get out, but the options for escape are limited. Some choose crime. A few with the talent try sports, and that was Dad's dream.

Venezuelans are crazy about baseball, the way Brazilians are crazy about soccer, and the amateur leagues there have been attracting major-league scouts for years. The country produced a Hall of Famer in the '50s in Chicago White Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio, plus a lot of other stars along the way. Today you could point to Bobby Abreu or Magglio Ordonez or Carlos Zambrano. Anyway, Dad also had talent. He's a lefty, and he could pitch.

By the time he was thirteen, baseball scouts had noticed him, but he'd also been noticed by a scout of another kind. Dad and a few of his buddies would make extra money singing on downtown street cornersâtraditional Latin stuff and songs from movies. One day a music executive named Domingo Villa stopped to listen, and he was sure he heard something special in Dad's voice. In two years, with Villa as his agent, Julio Costas had a bestselling album and an international tour, and the two men began to get rich together. Dad left baseball behind. Well, not entirely.

When he was twenty-five, my dad married his second wife, a nineteen-year-old Spanish tennis star who gave him three sons, my older brothers and me, before she and Dad split. I was only two when the divorce happened, but apparently there was some bitterness because she has never tried to involve herself with us. She married a Swiss doctor and is now raising a second family in Europe.

Meanwhile, Dad has married three more times, most recently a Vegas dancer seven years older than me. None of Dad's wives have really been “moms” to us, but it hasn't seemed like an issue. We've had nannies, Dad has always paid plenty of attention to us, and there's been baseball since we could walk.

Dad still dreams of sports glory, but now it's for his sons. So we've had private coaching, the best equipment money could buy, and constant encouragement. Well, “encouragement” is putting it mildly. Dad has always been pretty over-the-top about our working hard and succeeding in his favorite sport.

And, by and large, we've made him happy. My oldest brother Julio Jr. (J.T.) plays Triple-A in North Carolina, while Alex, the middle son, is getting attention as a catcher at UCLA. And Dad has the biggest ambitions of all for me. He thinks I'm the most athletically gifted of the three of us, and he wants results.

All three of us have played for the Roadrunners. In fact, Dad is probably the biggest financial backer of the team. He makes sure the team is what he calls a “class act.” We travel in comfort, and we stay at the best places when we're away. When we're at home, we have chartered time at a high-end gym and a part-time trainer to give individual attention to every team member.

It sounds like a great deal. But there's one problem. I am sick of baseball.

CHAPTER

3

I

've been playing baseball almost every day for a dozen years. And not just playingâtraining and practicing too. When I'm not on a field, I'm looking at videos.

Even when we were really little, it was all about baseball. On Monday nights when Dad wasn't performing, he'd sit J.T., Alex, and me down in front of the screen in our home theater for ESPN Monday Night Baseball. He would turn off the sound because he had no patience for the broadcasters. And he would comment on every play himself. We had to be ready for questions.

“J.T., pay attention. Why is the outfield playing in?”

“Alex, how come that pitch got by the catcher?”

“Can you believe it, Trip? The guy threw to first! What was the right play?”

This wasn't all crap. Dad knows baseball. And the three of us, by the time we were ten, knew it too. We'd been lucky enough to have talent and training, and we were all grateful and eager to please Dad.

It wasn't until I was thirteen that I expected anything more out of life than becoming a major-league star. When I did, it was because of Dad. Next to baseball, the biggest thing in our house, naturally, was music. Musicians came to see Dad, to jam with him, all the time. These guys were millionaires whose names weren't known outside of the small print on album credits, but they were legendary instrumentalists sought out by vocal stars like my dad who knew their value.