Out of Darkness

Authors: Ashley Hope Pérez

Text copyright © 2015 by Ashley Hope Pérez

Carolrhoda Lab⢠is a trademark of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansâelectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseâwithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Carolrhoda Labâ¢

An imprint of Carolrhoda Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at

www.lernerbooks.com

.

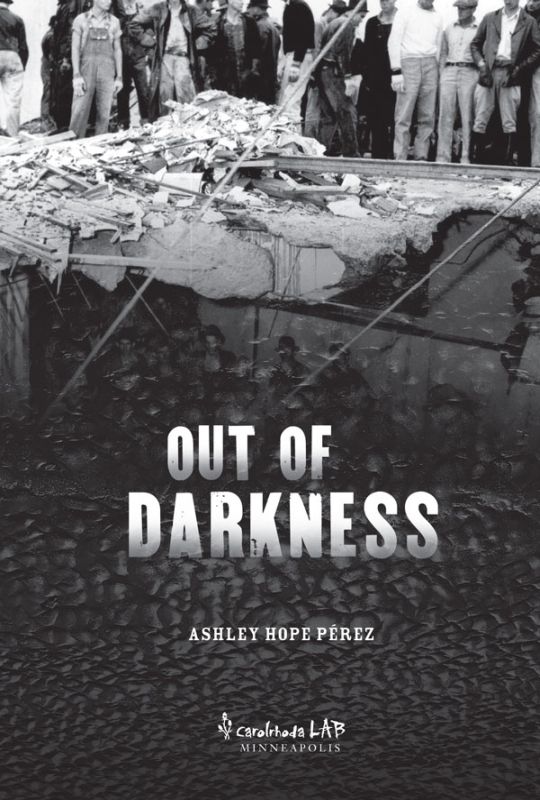

The images in this book are used with the permission of: © John Slater/Photodisc/Getty Images (woman with braid); © iStockphoto.com/DavidMSchrader (Old Stained Paper); © Jag_cz/Shutterstock.com (fire); © Roine Magnusson/Photodisc/Getty Images (bark background); © DeepDesertPhoto/RooM/Getty Images (house fire); AP Photo (building collapse); © iStockphoto.com/ilbusca (mud texture); © Bettmann/CORBIS (aftermath of explosion); © iStockphoto.com/RusN (burnt hole).

Main body text set in Janson Text LT Std 10/14.

Typeface provided by Linotype AG.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pérez, Ashley Hope.

Out of darkness / by Ashley Hope Pérez.

pages cm

Summary: Loosely based on a school explosion that took place in New London, Texas, in 1937, this is the story of two teenagers: Naomi, who is Mexican American, and Wash, who is black, and their dealings with race, segregation, love, and the forces that destroy people.

ISBN 978-1-4677-4202-3 (trade hard cover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4677-6179-6 (EB pdf)

[1. New London (Tex.)âHistoryâ20th centuryâFiction. 2. ExplosionsâFiction. 3. SchoolsâFiction. 4. Race relationsâFiction. 5. African AmericansâFiction. 6. Mexican AmericansâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.P4255Ou 2015

[Fic]âdc23

2014023837

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 â BP â 7/15/15

ISBN 978-1-46777-676-9 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-4677-7677-6 (mobi)

ISBN 978-1-4677-6179-6 (pdf)

In memory of my grandmother, Victoria Ray, who was one of the first to tell me about the New London explosion, and to my parents, who make East Texas home

Gather quickly

Out of darkness

All the songs you know

And throw them at the sun

Before they melt

Like snow.

âLangston Hughes, “Bouquet”

It was not darkness that fell

from the air. It was brightness.

â James Joyce,

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

PROLOGUE

NEW LONDON, TEXAS: MARCH 18, 1937

From far off, it looks like hundreds of beetles ringed around a single dome of light. Then the shiny black backs resolve into pickups and cars and ambulances. The bright globe divides into many lights. Work lamps. Spotlights. Strings of Christmas bulbs. Stadium floodlights borrowed from the football field nearby. Men and dust and tents. Thousands of spectators gather, necks craned. But it is not a circus, not a rodeo.

Within the great circle of light, men crawl over the crumpled form of a collapsed school. They cart away rubble and search for survivors. For their children. Mostly, though, they find bodies. Bits of bodies. They gather these pieces in peach baskets that they pass from hand to hand, not minding their torn gloves, torn skin. They say nothing of the stench.

A man squats and pulls away crumbled bricks. Under a blasted chunk of plaster he finds a small hand missing three fingers. He places it in a basket and heaves the debris into a wheelbarrow. Farther down in the tangle of wood and schoolbooks and concrete, he uncovers a bruised toe. Later he finds a child's leg, still sheathed in denim. Bent at the knee, it fits in the basket.

Red Cross volunteers with white armbands stand at the edge of the work site and hand out cigarettes and sandwiches. They pour scorched coffee into paper cups. As if nicotine, pimento cheese, and caffeine were any match for this horror.

Just after midnight it starts to rain, but no one runs for the tents. Some men take off their hats. Water runs down their faces, the perfect cover for tears. East Texas clay mixes with plaster dust from the school; red sludge sucks at the soles of work boots. But the floodlights and lanterns and lamps shine on, their collective light so bright that later people will say they saw it ten miles away, a beacon shooting up through the storm clouds. Across the school grounds and in the woods and in backyards and in every corner of the county, pumpjacks continue their slow rhythm, humping at the earth. Steady, steady, they draw up the oil that made this school rich.

Near dawn, every square foot of the collapsed building has been sifted and scoured for survivors and for remains. The rescue workers wander, stare, peel off their shredded gloves. They smoke and drink coffee, and then they climb into trucks and drive home. But the work continues as armies of undertakers and volunteers tend bodies in makeshift morgues. With no time for embalming, they brush the dead with formaldehyde from buckets. Eyes burn and swell shut from the fumes. Mothers and fathers walk among sheeted bodies, stop, move on. Faces are a mercy; most identifications come after scrutiny of birthmarks, scraps of clothing, scars.

There are not enough small caskets to go around. A call goes out for carpenters, and planks flow from the lumberyard into the pickups of anyone who can handle a hammer. Rough coffins come together, and a new round of digging begins; graves open up in rows.

For the next three days, alone or in numbers, families mourn their children and their neighbors' children. There are so many funerals that the pews in churches have no time to cool. Voices grow thin and hoarse from singing. Throats tighten. Consolation falters. Silence settles, and in silence they bear coffins. More than grief, more than anger, there is a need. Someone to blame. Someone to make pay.

THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 1937, 3:16 P.M.

WASH

Wash drove his shovel into the flower bed and turned the soil. Fast but not too fast; he had to be sure to earn out the hour. He liked working at the superintendent's place, liked being close to the school, liked how Mr. Crane always paid him fair. A quarter an hour was a decent take, and he was saving for third-class train tickets to the Mexican border, the price of a new life with his girl.

He pulled up a loose bit of clover and brushed his hands on his pants. He'd ask for more hours tomorrow. Now that the long, wet winter was over and it was warm enough for planting, Mr. Crane would want him to fill the flower beds with petunias and pansies and the little pink impatiens that his wife favored, color to tide her over until her azaleas and rose bushes bloomed. But today the weather was too fine to waste, the sky rolled out bright as a bolt of blue fabric, the warm breeze combing back the last of the chill. It was weather for being in love, and Wash was in love. He counted the minutes until Mr. Crane would be done with his meeting and could pay him and the minutes after that until his girl would be done with school and they could get to the tree and be together.

He was thinking out his first touch for herâa kiss, one hand to her long, soft hair, the other to her waistâwhen a thundering roar filled his ears. The ground bucked. The trees above him lashed back and forth.

Wash picked himself up and stumbled forward. When he rounded the corner of the house, he saw the walls and roof of the school crumple. He ran hard across the muddy schoolyard through drifting clouds of thick black and gray and white dust that choked and blinded him.

â â â

He found the side door of the school and stumbled into what was left of the main hallway. His arms went white with dust. Grit caked his tongue. He could hear shouts from the schoolyard. The building groaned around him, but there was no other sound inside.

He'd been in the school to do odd jobs, but he hardly recognized it now as the dust began to settle. The walls along the hall were blasted out, and what was left of the ceiling sloped at a dangerous angle. One brass light fixture dangled, bulbs shattered. He inched forward, boots crunching on broken tile. A few yards ahead there was a dark cavern where the floor had been. Above the hole, the ceiling and the second floor were completely gone. A patch of sky showed and then disappeared behind a cloud of dust.

He was edging toward the blown-out wall of a classroom when he saw it. A black shoe with a worn strap and a red button. A shoe he knew.

SEPTEMBER 1936

BETO

Beto jabbed an elbow at his twin. “That's no way to start our first day,” he said.

Cari ignored him and turned back to their older sister Naomi. “And if we don't follow Daddy's rules? He never got to make any before.” It was a challenge, not a question. Before Naomi could say anything, Cari ran farther down the path. She looked small amid the high straight pines. They stretched up fifty, maybe even a hundred feet before the first branches. Smaller trees with ordinary leaves grew between them.

Beside Beto, Naomi stayed quiet. Her fingers worked the ends of her long braid. Beto knew she would say something sooner or later. She was going on eighteen and in charge. And anyway, the new rules weren't so bad. Especially considering that they came with the new house and the new school, the new town and a new daddy. Daddy had been their daddy all along, only he hadn't been there so they hadn't known. Cari said they didn't need him; Beto thought they might.