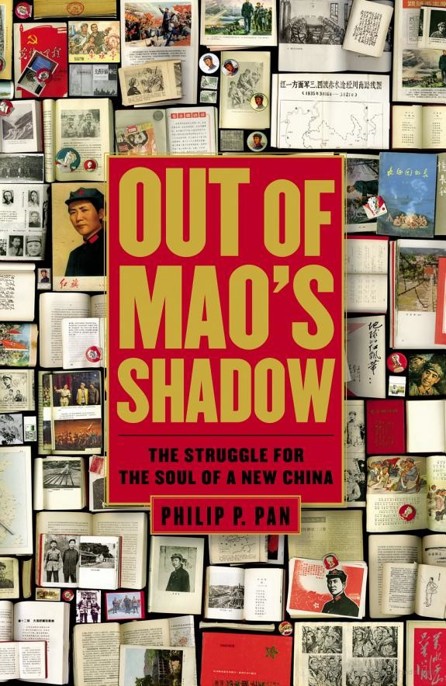

Out of Mao's Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China

Read Out of Mao's Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China Online

Authors: Philip P. Pan

Tags: #History, #Asia, #China, #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

I

LLUSTRATION

C

REDITS

Philip P. Pan: title page, Chapter 3, Chapter 10

Courtesy of Hu Jie: Chapter 2

Ji Guoqiang/ImagineChina: Chapter 6

Gao Zhan: Chapter 8(both photos), Chapter 9, Chapter 10

Taozi: Chapter 7

He Longsheng: Chapter 10

| 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 |

Copyright © 2008 by Philip P. Pan

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pan, Philip P.

Out of Mao’s shadow/Philip P. Pan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. China—Social conditions—1976–2000. 2. China—Social conditions—2000–3. China—History—1949– I. Title.

HN733.5.P36 2008

306.20951'09045—dc22 2008011550

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-7989-2

ISBN-10: 1-4165-7989-3

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Sarah and Mookie,

and for my parents

O

n a warm Friday night in the summer of 2001, I stood amid hundreds of thousands of young Chinese pouring into Tiananmen Square in a joyous and largely spontaneous celebration of Beijing’s successful bid to host the Summer Olympics in 2008. As fireworks lit the sky and blasts from car horns echoed across the city, the exultant crowd pushed through lines of riot police, filling the square and its surrounding boulevards. “Beijing! Beijing!” the revelers chanted, many of them waving little red Chinese flags. “Long live the motherland! Long live the motherland!” University students shimmied up traffic lamps, singing the national anthem and patriotic hymns such as “Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China.” Shirtless young men ran laps around the square, trailing red and green banners and shouting obscenities in jubilation. Bicycles, motorbikes, pedicabs, and cars packed the streets, the giddy people on board flashing victory signs. From atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace, where Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and where his portrait still hangs, the men at the helm of the Communist Party looked out on the masses and basked in the outpouring of national pride.

I had arrived in Beijing only months earlier, a new China correspondent for the

Washington Post,

and the collective outburst of joy in the political heart of the nation took me by surprise. Not since the prodemocracy demonstrations in 1989 had so many people converged on Tiananmen, and the contrast was inescapable and jarring. Back then, the multitudes of young people who filled the square were protesting the corruption of the Communist government and calling for democratic reform. The army crushed those protests, and in the early 1990s, when I was studying Mandarin in Beijing, the memory of the massacre still darkened university campuses. But now people seemed to have forgotten the party’s violent suppression of the democracy movement, and the crowds in Tiananmen were cheering the government. What had happened to the demands for political change? How had the party regained its footing? And how long could it hold on to power?

Over the next seven years, I searched for answers to these questions, a quest that took me to cities, towns, and villages across China. What I found was a government engaged in the largest and perhaps most successful experiment in authoritarianism in the world. The West has assumed that capitalism must lead to democracy, that free markets inevitably result in free societies. But by embracing market reforms while continuing to restrict political freedom, China’s Communist leaders have presided over an economic revolution without surrendering power. Prosperity allowed the government to reinvent itself, to win friends and buy allies, and to forestall demands for democratic change. It was a remarkable feat, all the more so because the regime had inflicted so much misery on the nation over the past half century. But as I examined the party’s success, I also saw something else extraordinary—a people recovering from the trauma of Communist rule, asserting themselves against the state and demanding greater control of their lives. They are survivors, whose families endured one of the world’s deadliest famines during the Great Leap Forward, whose idealism was exploited during the madness of the Cultural Revolution, and whose values have been tested by the booming economy and the rush to get rich. The young men and women who filled Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989 saw their hopes for a democratic China crushed in a massacre, but as older, more pragmatic adults, many continue to pursue political change in different ways.

In the three decades since Mao Zedong’s death, China has undergone a dizzying transformation. A backwater economy has become a powerhouse of manufacturing and trade, with growth rates that are the envy of the world. Skyscrapers have sprouted from rice paddies, gleaming cities from fishing villages. Infant mortality is down, and incomes and life expectancy are up. With economic change has come political progress, too. The terror campaigns that Mao favored, the mass denunciation meetings, the frenzied crowds of youngsters waving little red books—they are all things of the past. People enjoy greater prosperity but also greater personal freedom and access to information than ever before under Communist rule. By almost any measure, the country’s last twenty-five years have been the best in its five-thousand-year history. But the Chinese people have not yet escaped Mao’s shadow. A momentous struggle is under way for the soul of the world’s most populous nation. On one side is the venal party-state, an entrenched elite fighting to preserve the country’s authoritarian political system and its privileged place within it. On the other is a ragtag collection of lawyers, journalists, entrepreneurs, artists, hustlers, and dreamers striving to build a more tolerant, open, and democratic China.

The outcome of this struggle is important not only because half of the planet’s population without basic political freedoms lives in China, or because other governments around the world are already copying the Chinese model to curb demands for democratic change by their own peoples. It is also important because what kind of country China becomes—democracy, dictatorship, or something in between—will help answer one of the pressing questions of our time: How will the rise of China affect the rest of the world? In other words, the future of the Chinese political system could define how China behaves as an emerging global power, how it interacts with its neighbors in Asia and with that nation watching it so closely on the other side of the globe, the United States.

This book is an attempt to describe the battle for China’s future through the eyes of a handful of men and women. I begin in Part I with the efforts of individuals to unearth and preserve the nation’s tragic recent history. The party’s ability to rewrite the past is critical to its grip on the present and the future, and it has tried to maintain a sanitized account of events that serves to justify its rule. But, from the violent beginnings of Chinese communism to the Tiananmen Square massacre, society is beginning to recover the truth. Part II explores how the party evolved after Mao’s death and adapted to survive. The totalitarian, socialist state that Mao built is no more. In its place is a more cynical, stable, and nimble bureaucracy, one that values self-preservation above all else and relies on an often corrupt and predatory form of capitalism to survive. This section tells the stories of miners and factory workers left behind and the apparatchiks and tycoons who thrived. I conclude in Part III with four ordinary people who tried to push the limits of what is permissible in China just as a new party leadership raised hopes of democratic progress. Thrust into the national spotlight, they are forced to make difficult decisions about when to fight and when to back down, and to weigh the consequences of their choices for their families and their nation.

Having tasted freedom, having learned something about the rule of law, having seen on television and in the movies and on the Internet how other societies elect their own leaders, the Chinese people are pushing every day for a more responsive and just political system. The party has struggled to adapt and sometimes retreated in the face of such popular pressure, but it has not yet surrendered, not even close. Its leaders, and its millions of functionaries and beneficiaries, continue to cling to power, marshalling their considerable resources in a determined and often obsessive effort to maintain control over an increasingly vibrant society. Many people who care about China tell themselves that democratization is inevitable, that the people will eventually prevail and the one-party state will fail. I certainly hope so. But I have seen that there is nothing automatic about political change. It is a difficult, messy, and often heartbreaking process, and it happens—when it happens at all—because of imperfect individuals who fight, take risks, and sacrifice for it. They can be noble, courageous, selfless, stubborn, vain, naive, calculating, and reckless, and I was fortunate to meet so many of them during my time in China. Their stories inspired this book.