Out of the Dragon's Mouth

Read Out of the Dragon's Mouth Online

Authors: Joyce Burns Zeiss

Tags: #teen, #teen fiction, #ya, #ya fiction, #ya novel, #young adult, #young adult novel, #young adult fiction, #vietnam, #malaysia, #refugee, #china

Woodbury, Minnesota

Copyright Information

Out of the Dragon's Mouth

© 2015 by Joyce Burns Zeiss.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Flux, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author's copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover models used for illustrative purposes only and may not endorse or represent the book's subject.

First e-book edition © 2015

E-book ISBN: 9780738744322

Book design by Bob Gaul

Cover design by Lisa Novak

Cover image: iStockphoto.com/7283342/©NuStock

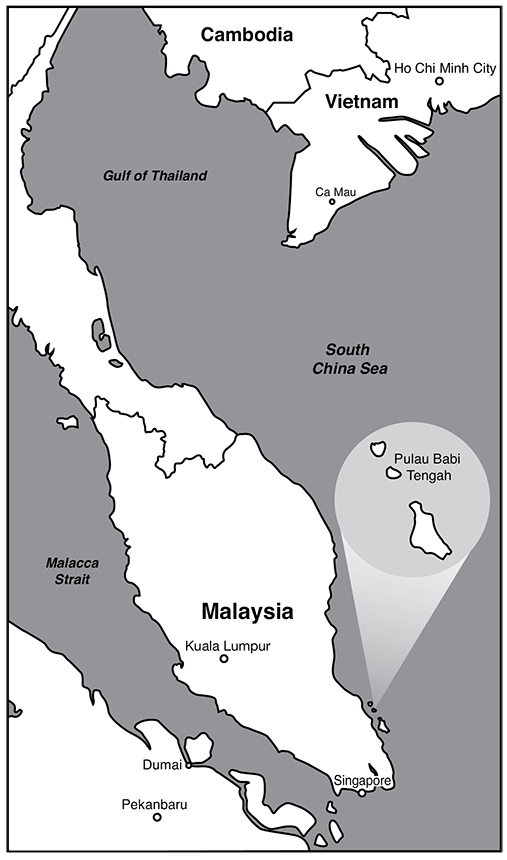

Malaysia Map by Llewellyn Art Department

Flux is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Flux does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher's website for links to current author websites.

Flux

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.fluxnow.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

To the Vietnamese boat people

One

The darkness covered Mai like a burial shroud. She huddled in the small space allotted her, crushing her knees to her chest, struggling to breathe. The sickly smell of diesel fuel and the stench of human sweat engulfed her. Around her pressed a mass of human shapes, and a heat so heavy she thought she would faint. Soft moans and nervous whispers sifted through the stagnant air.

Above her, through a small opening, was a slice of blue sky, a whiff of the sea. She gasped and exhaled. The screech of the engines pierced her ears as the last refugee squeezed into the hold. Then she felt the fishing trawler rock against the waves, chugging down the river. She choked back a sob.

A crewman with a jagged scar on his bare chest peered through the hatch opening. “We're nearing the ocean,” he cautioned. “Stay out of sight until we get past the patrol boats. Not a sound.” The hatch cover dropped. Someone coughed. Then there was silence except for the sloshing of the waves.

Where were they going? Somewhere across the oceanâfar away from Vietnam, far away from her family and home. Father had mentioned Hong Kong and Malaysia as he told her of the refugee camps. “From there, the Red Cross can help you get to America,” he had said. “And soon we'll join you.” She could still see his eyes, dark and desperate. Hong Kong. Malaysia. Strange names that meant nothing.

Father, father, I don't want to go.

You have to,

he had told her.

You have to go to survive

.

But what if I don't survive,

she thought.

You're not here to help me.

She wished she were near Uncle Hiep, Father's youngest brother, but he was somewhere in the back of the boat. Dear Uncle Hiep. How she loved him. Even though he was nineteen, five years older than her, he was her favorite uncle, the one who paid attention to her when her parents were too busy. He lived in the family compound in a long house next to hers, and he always had time for her. When they'd arrived at the trawler earlier that day, he'd found her this space in the bow near the hatch.

She lowered her head between her knees and pushed her nails into her calves. The small red bag containing

banh te

, a mixture of rice and beans wrapped in banana leaves that Mother had packed for her, sat wedged between her feet. She felt the waistband of her loose pants where Mother had hidden two gold bracelets.

“These will bring you good fortune,” Mother had said, pushing the needle through the soft fabric. “Don't tell anyone.” Mai remembered how her mother's long black hair fell forward, hiding her sunken cheeks and her tired eyes. She seldom smiled these days, her brow always furrowed and her words short and few. Mai longed for the touch of her mother's hand on her cheek or a warm embrace.

The rough arms of an old woman pressed against her, and Mai felt a sharp elbow digging into her back. In front of her, a mother's arm enfolded her young son. He peered at Mai, his cheeks flame-red, his listless head propped against his mother's shoulder. Arrows of sunlight revealed the shadowy presence of a sea of heads and bent backs, packed like fish for market. A woman sobbed in the dark behind her.

Mai bit her lips until she could taste blood.

The drone of the engines suddenly stopped and she heard sharp voices overhead and the clump of heavy boots. The soldiers were on board, inspecting the ship. She held her breath and prayed. If they were caught and jailed, who would know where they were?

The baby next to her started to wail. She could feel the mother's arm when she raised her hand to muffle its cry. She waited to be discovered. The voices above grew louder. For a moment, she hated that child. Would all be lost because of one cry? A long silence. The boots clumped away, and the engine resumed its steady hum. Mai exhaled.

They've gone. We're safe.

The hatch cover lifted. Fresh sea air and sunlight

painted the hold. The crew man shouted down, “We're in international waters now. We've made it.” A song broke out.

The rice Mai had eaten for breakfast started to rise in her throat. The plastic bagâwhere was it? Everyone had been given one. Now she knew why. She shoved it over her lips just as a stream of yellow liquid spewed forth, leaving a foul taste in her mouth. She wiped her lips with the back of her hand and gagged. Nothing came up. Oh, to be out of here. The boat lurched, plowing through the sea while Mai covered her ears to block out the wails from the men, women, and children packed in this prison. The pungent smell of vomit filled the air and small pools of liquid puddled on the rough planks beneath her. Finally, the water grew calm. The incessant rocking ceased. The hold grew silent.

She thought of what Father had said about October. “It's a good time, the end of the rainy season. Fewer boats will be out looking for escapees in this weather.”

She hoped he was right. It seemed much longer than two weeks ago that she'd overheard Father and Mother talking while she was lying on her mat in the storeroom they shared at her grandfather

Ã

ng Ngoai's textile factory.

“I've saved enough gold to get two out. Hiep's got to go now.” Father's voice was low. “The Communists will send him to fight in Cambodia.”

“Send Loc with Hiep,” Mother pleaded. “They're taking fifteen-year-olds now too.”

Mai had shuddered to think of her studious elder brother fighting.

Several days later, her father told them of the secret plan. “Hiep will leave with Loc and the rest of the family will follow, a few at a time, as soon as the passage money can be obtained.” He ran his hand through his short, thick hair. “A fishing trawler, captained by my cousin, will be waiting to take Hiep and Loc across the South China Sea.”

This was the only way. The new government of Vietnam would allow no one to leave.

Mai had felt relieved yet frightened. She'd heard stories of Thai pirates who attacked refugee boats, robbing, raping, and killing, of boats that sank in raging storms, drowning everyone. She was glad they were sending Loc instead of her. Then she felt guilty. What if something happened to Loc? Her parents' hearts would be broken. Oh, she was such a bad girl. But she couldn't help the way she felt. She didn't want to go.

But the night before he was to leave, Loc had complained of a sore throat.

“You feel like a hot coal,” Mother had said, placing her hand on his forehead.

Father looked at him and said, “The journey will be hard. You'll have to wait.”

Mai had stared at her bowl of rice, waiting for his next words.

“Mai will take Loc's place.”

A glob of rice had lodged in her throat. Shocked, she had thrown down her chopsticks and clutched Father's hands.

“I don't want to go without you,” she cried.

“You're in danger, too. Even fourteen-year-old girls like you are being forced into the army now.” The veins in Father's short neck bulged.

She clutched his hands and pleaded, but Father's face was unmoving, like the stone Buddha statue in the temple where they went to celebrate the Moon Festival.

She had never been away from her family. The daughter of a wealthy rice exporter, she had spent her life on the Mekong Delta near Can Tho, playing with her brothers, Loc and Quan, and her two sisters, Tuyet and Yen, along the river.

“Mekong means âriver of nine dragons,'” Father had told them. “It flows from far away in the mountains of Tibet.” He pointed to a map.

The war had been raging for as long as she could remember. The Americans had come to South Vietnam to help them fight for democracy. North Vietnam, under its leader, Ho Chi Minh, a funny-looking man with a long white goatee, was trying to take over South Vietnam and make Vietnam all one country. But North Vietnam was Communist, and Father shook his head. “We don't want to be Communist. We want to be a democracy. Why don't they leave us alone?”

In the blackness of the boat's hold, Mai prayed to her great-grandfather's spirit for protection. His picture had hung above the incense burners at their family altar in the large house they shared with Father's parents. He looked rather forbidding with his goatee and his bushy eyebrows, but he must have been handsome in his youth because he had managed to win the hand of the mayor's daughter.

Mai remembered her father telling them how Great-grandfather had fled the Communists in China and come to Vietnam, where he had worked for the mayor of the province as his bookkeeper. Because he had been so trustworthy, the mayor had allowed him to marry his ninth daughter and had also given him much land. This land had now been in their Chinese family over four generations. “Please, Great-grandfather, protect us,” she murmured.

Mai felt a painful pressure in her bladder. She'd tried not to drink too much that morning, but by now it must be afternoon. She could hear a voice from above, calling people up to the deck in small groups.

“You, come on. Get up here,” ordered one of the crew.

Mai tried to stand, but her legs crumpled like wooden stumps. Sharp needles shot through them. She struggled through the hatch. Sun-blind, she swayed with eyes closed. A metal cup brushed her hand. Through half-open eyes, she could see water in it, could smell its wetness. She raised the cup to parched lips and let the warm liquid trickle down her throat. Opening her eyes wider, she could see tiny palm trees dissolving, the coastline slowly shrinking. The emerald-green sea swelled beneath her. Over the bow, a dappled sky.

Hiep, along with several other young men, was relieving himself over the rail. Several women and children formed a line by the rail behind the engine house, where a small box was suspended on a rough plank over the water. Mai joined them and watched as a young girl climbed into the box and sat down, her head poking up above the edges.

The pressure in Mai's bladder was unbearable. When it was her turn, she climbed over the edge of the box and pulled her pants down. Squatting on the plank with the hole in it, Mai peered down at the waves rolling below. A gush of warm urine shot from between her legs. She kept her eyes lowered, trying not to look at the people waiting their turn.

She remembered the day the pimply-faced young Communists clad in black shirts and pants, wearing

d

é

p

âflip-flopsâmade out of old bicycle tires, had come to Rai Rang to take their house. Such peasants. They'd looked more like farmers than soldiers. They had never seen an indoor toilet. They caught fish from the river and deposited them in the shining toilet bowl to keep until they were cooked. How could such backward people have won the war?