Outposts (17 page)

But the Imperial splendour here is all illusion. True, the Gibraltar Conservation Society makes an almighty fuss whenever a new block of army flats or a multi-storey car park threatens some of the magnificently immense fortifications—the great gates and bastions and casemates and galleries, the mighty limestone blocks and rusty iron stanchions, bolts, hasps, anchors, cannonports, naval guns and sea walls—which are undeniably grand reminders of such splendour. The fortress and all its remnant bits and pieces tell of Trafalgar and Cape St Vincent and the wartime convoys, of heroism and valour and tragedy, and there is the whiff of convict ship and merchant venturer, the memory of sail and steam and majesty and power.

And true, there is a flourishing democracy here, though of recent invention, and of limited democratic ability. Until the Thirties the only form of local government was the Sanitary Commission, run by a cabal of traders and lawyers, and which was set up in 1865 after an epidemic of plague which killed nearly 600 people. The commissioners had powers that extended well beyond a purely sanitary remit; in 1920 they were able to report that a poor law was unnecessary in the colony, and there was no one to suggest they should stick to the study of tuberculosis (which was then raging) rather than poverty. The Legislative Assembly, which gave a

semblance of power to the Gibraltarians, was opened in 1950 by the Duke of Edinburgh; it became an even more powerful House of Assembly in 1969, though the Governor—who is also Fortress Commander—still has very considerable powers.

But the glorious ruins of yesterday and the laudable institutions of today cannot disguise the fact that Gibraltar is, above all, a garrison town, with all that implies. Its function is precisely that of a Tidworth or a Fort Bragg—it supports and supplies a military function, and its civilian servants exist only in a symbiosis with the forces, with no real function other than to service the machinery of war.

During the Falklands War Gibraltar was of major importance—a fact that nearly led to one of the more daring undercover operations of the century. A team of Argentine frogmen arrived in Spain with plans to swim over to the Rock and blow up the Royal Naval ships in the dockyard, and then lay charges inside the more important of the tunnels, and blow the entire Rock up, too. But the Spanish police, tipped off by British intelligence, arrested the quartet at San Roque, just a few miles from the border. The Spanish Government, which despite its antipathy to Britain wanted membership of the Common Market and had good reason to want to stay friendly, deported the men and sent them back to Buenos Aires. I was told the story in Hong Kong, which was ordered to keep on guard in case the plucky Argentines tried to pull a similar stunt there. People on the Rock knew nothing at the time; on the day the men were detected a parson friend of mine was sailing back from a day’s shopping in Tangier, and remembers ‘sitting on the boat as we rounded Europa Point, shelling Moroccan peas so they were ready for the deep-freeze the moment I stepped ashore’.

Today the Rock draws its military significance wholly from its membership of NATO (of which Spain is a member, too). America, in particular, regards Gibraltar as crucial, for though her own submariners use the port of Rota, just a few miles westwards, for their nuclear patrol boats, there is inevitable doubt about Spanish stability, and thus no long-term certainty inside the Pentagon that Rota will be perpetually available, unlike Gibraltar, which will so long as it remains British. Washington regards the defence of the

Rock with almost as much passion as do the politicians in London. The Pentagon counts the apes as well.

No garrison town holds many attractions, and Gibraltar is not an exception. Though geologically interesting and thus topographically unforgettable, it remains, as Jan Morris noted in 1968, ‘only a fly-blown, dingy and smelly barracks town, haunted by urchins fraudulently claiming to be Cook’s guides, or Spanish hawkers wandering from door to door with straggly flocks of turkeys’.

It was grander once. You could, on a day when the fleets were in, stand under a palm tree on the terrace of the Rock Hotel and gaze down with wonder and amazement at the glittering array of grey steel and holystoned decking, at the signal flags and the jolly-boats, at the jackstaff ensigns waving lazily in the air, arrogantly proclaiming raw and unchallengeable British power. But now there is no Orient route that needs guarding, nor any fleets of substance with which to do it. Gibraltar, so far as the British are concerned, is a pointless sort of place: we hang on because the Gibraltarians want us to, because we have a certain haughty pride about the Rock’s impregnability, and because the Supreme Commanders of the North Atlantic like us to act as proxy for them in this convenient corner of a geopolitically important inland sea.

Britain has offered a special gift to those whom we regard as of such special military significance—even if we have no further grand wars to fight, and even if the natives of the Rock are mere supporters, not participants. In gratitude for all their help the British Government has made the Gibraltarians, unlike most of their colonial colleagues, full-blown British subjects, able to come and live in Britain with no restrictions at all. They were given the privilege in 1981, when the House of Lords voted that they should not be treated like Bermudians, the Pitcairners, or the Hong Kong Chinese, who would no longer be allowed to enjoy full citizenship of the motherland. (The Falkland Islanders were not given citizenship either on this occasion, though after the war the Government changed its mind. The Gibraltarians and the Falklanders are thus unique in two respects—unlike all other British colonial citizens they can come and live in Britain at any time they wish; and unlike

all other British colonial populations, they are overwhelmingly coloured white. Any connection between the two is not, as one might suppose, rigorously denied. The British Nationality Act, the basis of all this complicated regulation, was specifically designed to minimise racial disharmony by keeping the number of yellow and black colonials out, while letting whites of British ancestry come home if they wished. The Genoese and the Sephardim of Gibraltar have much to be thankful for.)

And, like the apes, so the British Gibraltarians cling on. At the last count, just forty-four of them thought it a good idea to join back with Spain. Twelve thousand voted for Gibraltar to remain a member of the Empire. So every night the fortress keys—cast iron, weighing ten pounds, and kept by some of the more nervous governors under their pillows, it is said—are handed into safe keeping by the sentries who still yell out the Imperial formulae of three centuries continual use:

Halt! Who goes there?

The Keys

Whose Keys?

Queen Elizabeth’s Keys

Pass, Queen Elizabeth’s Keys. All’s Well.

All illusion, though. From the Rock Hotel, with no fleet in view, and no reliable kippers available, and Brown Windsor soup and rolls served at nearly every meal, and the same faces passing along the same streets, the same soldiers inviting you to the same drinks parties, the same films on at the same cinemas, and the same awful weather and the same awful apes, I, too, felt like Mr Bula, trapped and claustrophobic, wanting to get off to the apparent freedom of Algeciras, whose lights twinkled invitingly from across the bay.

The terminal was crowded with servicemen bound for home leave; few Gibraltarians were planning to desert the peninsula this particular Saturday. I sat on the right side of the aircraft, and watched with a mixture of awe and some relief as we rose beside the mighty

white cliff, dotted with its cannonports, topped with artillery and radio aerial and the Union flag, and headed back home to England. As a structure, it had been an impressive place, all right; but when a soldier caught my eye and grinned and said how glad he was to be getting away, I knew exactly how he felt. The Rock, he remarked, as he tucked into his first beer of the holiday, was also the name they gave to Alcatraz.

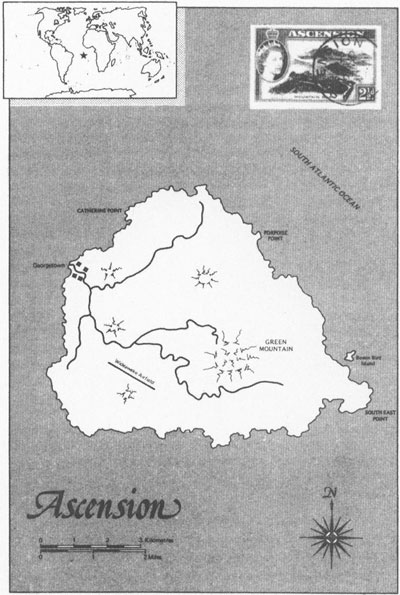

Ascension Island

Ascension Island

One of the more eccentric practices of the Empire was to decide that certain of the more remote island colonies were not really countries at all, but ships.

There was, for example, a tiny morsel of granite in the Grenadines that was taken over by the Royal Navy in Victorian times and commissioned as HMS

Diamond Rock

; then again, during the Second World War the Navy possessed a craft called HMS

Atlantic Isle

, which in more peaceful times was the four-island group of Tristan da Cunha. And in 1816 a Mr Cuppage, a post-captain of the Cape Squadron, took command of a brand-new ‘stone frigate’, as the Lords of the Admiralty liked to call it: the thirty-five-square-mile, oyster-shell-shaped accretion of volcanic rubbish that was assumed into the service of the Crown under the title of HMS

Ascension

.

I first saw the vessel—‘a huge ship kept in first-rate order’, Darwin had recorded—from the flight deck of a Royal Air Force VC-10, one steaming day in late July. We had flown from a base in Oxfordshire to Senegal, and I had become rather bored by the curious Air Force practice of putting its passengers facing backwards. (They say it’s safer.) So I asked to sit behind the pilot for the next leg; and as we reached the equator, and summer became technical winter and in a million bathrooms below the water began to swirl down plugs the other way, so the loadmaster called me forward, unlocked the door to the cockpit, made a series of perfunctory introductions to the crew, asked me to avoid sudden movements and unnecessary conversation, and strapped me into the jump seat.

Ascension Island came up on the radar a few moments later. A tiny pale green dot, lozenge-shaped and utterly alone—it might

well have been a ship adrift in the sea below. We started to go down for the approach. The orange numerals of the satellite navigator showed our position six times a minute. We were at fourteen degrees west of Greenwich, seven degrees south of the equator, somewhere in the hot emptiness of the sea well below the bulge of West Africa. The dot on the radar was bigger now, and we were low enough to see the white curlers on the swell.

And then the pilot muttered softly into his microphone, ‘Island in sight. Ahead fifty miles. Plume of cloud.’ And on the curved line of horizon a patch of cloud appeared, like a ball of cotton wool on a glass ledge. Beneath it, and speeding nearer at six miles a minute, was a patch of reddish-brown land, tinged with dark green and ringed by a ragged line of surf. ‘Wideawake Airfield in sight, sir,’ sang the co-pilot—and there, on the southern side of the island was the aerodrome, its straight runway undulating over the contours like the final run on a roller-coaster. A smooth American voice came on the line. ‘Ascot Two zero one niner—good day, sir. Welcome to Ascension Island. Wind eight knots. Clear skies at the field. No traffic. Come right on in, and have yourselves a nice day!’ And so we slid down the glidepath to this loneliest of ocean way-stations, until with a bump and puff of iron-red cinder-dust we touched down on board and I, who alone in the cockpit had never been here before, thought we had landed on the surface of the moon.

Ascension is indeed an eerie place. It is a volcano, placed on the very crest of an abyssal suture line, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and is in consequence very new. (St Helena, which lies some miles off the ridge, but is one of its products, is one of the oldest oceanic islands known. Geologists explain it by asking one to imagine a mid-Atlantic conveyor-belt moving islands out and away from the ridge. Those on it—Tristan, Iceland, Ascension—are still being formed; those away from it—the Azores, Jan Mayen, the Canaries—are old, and have drifted miles since their formation.)

Ascension looks as though it should still be smouldering. ‘Hell with the fire put out,’ someone called it—and it looks rather like a gigantic slag-heap, with runs of ashy rubble, piles of cinders, and

fantastically shaped flows of frozen lava. Nothing—at least, not among the peaks and plains I saw as I drove from the airport—had been carved by weather, nor has anything had its outline smoothed by millions of years of erosion. Ascension is the earth in its raw state, unlovely and harsh, and grudging in its attitude to the life that clings to it. It gives uncomfortable seismal shudders from time to time, and lets out puffs of sulphur gas and gurgles of hot water and mud, as if to warn those who have dared make this a colony of the British Crown that the lease is far from permanent, and the titanic forces beneath the rocky skin are merely slumbering, biding their time.

Ascension—which is very much an island of the space age today, festooned with aerials and chattering with computers and radar domes—was classified as a ship for rather more than a century. The Navy took it over in 1815 once it had been decided to exile Napoleon on St Helena, 700 miles to the south-east, and the Admiralty feared the French might try to take Ascension and use it as a staging base for helping the Emperor escape. (A garrison was established on Tristan da Cunha for the same reason.) It became a ship of the line a year later, with those few who lived aboard subject to the same rigours of ‘rum, sodomy and the lash’ as on any of Her Majesty’s vessels. One captain was sent a report to the effect that a member of his crew—a lady—had given birth to an infant. With mirthless propriety he jotted one word on the announcement—‘Approved’—and added his initials. (For years afterwards any children born on Ascension were officially deemed to have been born at sea, and registered according to custom in the London parish of Wapping.)

The Crown took charge of the island in 1922, and made her what she is now—a dependency of St Helena. There is an Administrator, who lives in what was once the sanatorium high up among the clouds on Green Mountain; and there is no permanent native population. There is, however—and has been for many years—a very considerable clutch of transients—people whose nationalities and trades vary according to the use to which Ascension is being put at any one moment. At the time I arrived, in the aftermath of

the Falklands operations, the island was crawling with Royal Air Force men and their planes, and all the paraphernalia needed for keeping the garrison in the far South Atlantic equipped with all it needs; but there have been at one time and another a bewildering variety of ‘users’ of Ascension. (The place is essentially run by a body known as the London Users Committee, who, since there is no native to inconvenience, do with the island more or less as they like, so long as they all agree it will do the users some good.) There have been missile-testing engineers, satellite trackers, radio broadcasters, spies (there are still lots of this particular breed) and those most indomitable guardians of the distant rocks, the men of the cable terminals.

Ascension Island was one of the great cable stations of the Imperial universe. The Eastern Telegraph Company arrived in 1899, bringing the free end of a cable that its ships had laid from Table Bay to Jamestown, in St Helena. Within weeks, after the repeaters and amplifiers had been built on Ascension, and a staff left behind to maintain them in working order, so the line was extended—up to the Cape Verde Islands, and then on to England. More cables were fed into the sea—one from Ascension to Sierra Leone, so the Governor in Freetown could send messages to Whitehall without having to wait if a camel had munched its way through the line across the Sahara. A fourth was sunk to St Vincent, a fifth to Rio, and another to Buenos Aires. By the time of the Great War Ascension sat in mid-ocean like a great telegraphic clearing house, the hum of generators and the clack of the morse repeaters echoing across the silence of the sea. (Ascension had always had associations with communication. As soon as Alphonse d’Albuquerque discovered it, on Ascension Day, 1501, sailors travelling past in one direction started a custom of leaving letters there, for collection and onward transmission by ships sailing in the other. There still is a letter-box where passing vessels may drop notes; when someone looked in it recently there was a note dating from 1913.)

Lonely places, cable stations. Islands like Fanning, in mid-Pacific, notable only because ‘it was annexed by Britain in 1888 as the site for a trans-Pacific cable relay station’ or Direction Island, on

Cocos-Keeling, ‘administered by Britain for a cable relay point for the Indian Ocean’ or Ascension. The British saw cables as the vital synapses of the Imperial nervous system. They had to be utterly reliable. They had to be secure. And they had, all of them, to be British. (To illustrate the point it is worth noting that when the time came to construct a cable from Hong Kong to Shanghai the cable engineers built a relay station on a hulk in the middle of the Min River, rather than risk placing so critically important an Imperial nerve-ending on Chinese soil, where anything might happen to it.) The ultimate purpose of the cables was, of course, the unity, and thus the unassailability of the Empire, a theme Kipling was quick to recognise:

Joining hands in the gloom, a league from the last of the sun

Hush! Men talk today o’er the waste of the ultimate slime

And a new Word runs between: whispering, ‘Let us be one!’

And so between them the sailors and the cable men built a society on Ascension, and a tiny Imperial city, which they called Georgetown (though it was always known as Garrison). A tradition grew up that every sailor—and later every cable man—brought something to render the moon-scape a little more like home. The Royal Navy and the Royal Marines, who from time to time were also posted aboard HMS

Ascension

, carried in scores of tons of earth and thousands of sapling trees (yews from South Africa, firs from Scotland, blue gums from New South Wales, castor-oil bushes from the West Indies); marines built a farm and brought a herd of cows (the milking shed, robustly Victorian and made from stone, has a crest and the letters ‘RM’, which the lowing herds blithely ignore); sailors dug a pond at the very top of Green Mountain, and stocked it with goldfish and frogs; and they built greenhouses and a home garden, and grew bananas and paw-paws, grapefruit, grenadillas and tomatoes, roses and carnations and all the familiar vegetables of an English Sunday luncheon.

Over the years the colonists have tried so very hard to impose the contented ways of a London suburb on this monstrously ugly

pile of clinker and baked ash. There was probably no place on earth that can have seemed less like home, no atoll or hill station or desert oasis that can have been less sympathetic to the peculiar needs of the wandering Englishman and his family. But, like the good colonist that he was, he did eventually manage to fashion the place into an approximation of Surrey-in-the-Sea. The little houses each have a neat garden and tiny patch of lawn, most of them with a round plastic swimming pool, a child’s swing and a snoring dog (‘we inherited the old boy from the Parker-Bruces, you know. Eats us out of house and home. Can’t think why he doesn’t roast, with all that hair. Goodness knows what will happen when we go. He’s getting on a bit. I suppose he’ll just go to whoever takes our place. Poor old devil. Lucy’s quite attached to him now. But then she was positively transfixed by that old mutt we had in the Seychelles. Got over him in time, of course. But it can be tough on the kids…’). There is a library and a hairdresser for the wives, and there are drinks parties most evenings—a lot of drinks parties, a lot of drinks, and the usual alcoholic haze of tropical solitude.

The

Islander

newspaper has been coming out each week, thanks to the labours of any number of Our Lovely Wives, since 1971. Take a riffle through the pages of one recent March issue. There’s old Brian presenting a teak tray and a couple of tankards to Margot and Dennis, who have just left after their two-year stint; Pearl Robertson has won the whist competition up at Two Boats, yet again! (The road up to Green Mountain has sawn-off gigs stuck into the clinker to act as milestones—One Boat is lower down, Two Boats is up at the 700-foot mark—and small communities, and telephone exchanges, have grown beside them. The boats act as splendid shelter from the occasional violent rainstorms.) Now, what else? Margaret Lee will give a manicure demonstration on Wednesday at the Two Boats Club. Suzanne will host a Tupperware patio sale in Georgetown on Saturday. Communion will be at nine thirty this Sunday at St Mary’s. Novice bridge players are welcome at the Exiles Club library every Wednesday at 8 p.m. Irene Robinson wrote to say she was leaving the island and would miss the Church, the Scouts, the Gardening Club and the Tennis Club. A vote of

thanks had been organised for Ernie Riddough, who was also leaving: his term as public health officer had been a great success, and ‘the island had not suffered from plague and pestilence’. The Messmen would play the Supremes in the island darts league on Tuesday, and there would be a soccer match, Georgetown versus the Forces, the day after. And—best news of all—the Ascension Cricket Association has just received two dozen balls from St Helena, the cricket league can now get under way, and a meeting would be held on Tuesday night beside the Volcano Radio Station to discuss the season’s fixtures.

There is no hotel on the island. Visitors are not encouraged—the lack of hotel room being the official excuse. I have stayed in a variety of places. The Americans have huts they call ‘concertinas’ they are shipped over quite flat, like sandwiches, and then the ends are pulled apart and a fully-equipped room appears, with mirrors on walls, lights in ceilings, tables clipped to floors. Each time I slept in Concertina City—which was difficult anyway, because of the heat—I started to wonder if the whole room might revert in the night, and I would be flattened out of all recognition, as though I had been trapped in the boot of a car sent to the crushers.

My happiest nights were spent at the old Zymotic Hospital. It had been built by the Navy more than a century ago, perched on a cliff of slag, facing west; it has thick stone walls, and gently turning fans, and the windows and the doors are always open. It is perfectly cool, and I would sit there with the crews of the transport planes, sipping whisky and watching the sunsets, and listening to stories of airborne exploits in every Imperial corner of the world. I found one pilot whom I had known at school; another who had once given me a lift during the rescue operations following a hurricane, from British Honduras to Costa Rica; and a third who had been a member of the Queen’s Flight and had spent the last summer shuttling the Queen Mother back and forth from Windsor to Glamis.