Oz Reimagined: New Tales from the Emerald City and Beyond (43 page)

“Yes, out over the Deadly Desert. It’s a miracle I landed in Kansas.”

“You should have seen what I went through to get them back.”

“I’m flattered,” whispered Dorothy.

“Twenty Munchkins on four magic carpets, so they might never touch the life-sapping sands for more than an hour or so at a time. Nick Chopper led the expedition for me, since he’s the ruler of Winkie Country now. Their journey took a year, flying each day from the realm of the Squirrel King out over the wastes. The Munchkin members of the expedition all returned as old men, wizened and hobbled, their life drawn away by treading the interminable dunes. The Tin Woodman, of course, didn’t age, but the fierce winds blew sand against him, scratching their will into his metal form. Finally, one day, they spotted something glittering in the distance.”

“But the sands were deadly? When I was here last, an enchantment had been cast to make all in Oz ageless,” said Dorothy.

“Yes, well, my dear, in a land of magic, all things accomplished by enchantment can be just as easily undone.”

“And what undid that spell?”

“It’s a long story,” said the Wizard. “But an interesting discovery of the expedition, other than the shoes, was that the Deadly Desert, at its farthest reaches, is littered with fossilized corpses, frozen in the act of trying to reach the Land of Oz. They brought me one of these unfortunate Desert statues, a man who had turned to leathery rock, and I saw that this person was a gentleman from Kansas, or Nebraska, or Oklahoma, etcetera, etcetera. Hundreds of souls, burnished by the sand and the bright Desert sun, seized in the pursuit of their desire to reach this place. The poor fools didn’t know that you can only find Oz without a map.”

Dorothy closed her eyes and pictured the stony forms, covered to the elbows in sand, leaning forward in their desperation. As she shook her head, the tea whistle blew, and the Wizard got up to fetch the cups.

“Well, the world is not what it used to be,” she said.

“Here or there?” he asked, pouring the hot water.

She looked around at the rug, the tablecloth, his smoking jacket—all threadbare. There was a crack in the glass fixture of the gas lamp. The books and knickknacks on the shelves hadn’t been dusted in an age. “I guess both,” she said. “More there than here, though.”

“I had my spies,” said the Wizard, dipping the tea ball as if he was fishing for snappers. A delicious fruit smell pervaded his parlor.

She reached for the gun but caught herself at the last second and directed her hand to her face, where she scratched a nonexistent itch. “How much do you know?” she asked.

He set her tea down in front of her and then his at his place. He took a seat and smoothed the front of the smoking jacket over his gut. “From your earliest days after you last left Oz. The year you were twelve and began working in the leather trimming factory, your hunger, your poverty, your innocence. No parents to guide you or look after you.” He scowled, and she almost believed he meant it.

Dorothy nodded. “I suffered for my decision to go back. Fourteen-hour shifts, a bowl of gruel, the heat, the constant grinding noise and darkness, the groping hands of filthy men. All that while carrying in my head a knowledge of the gleaming Land of Oz. Every fall was made harsher, every disgrace more obvious for having traveled the road of yellow brick.”

“Why did you leave?” he asked. “You could have stayed here and never even grown old. Been eleven forever.”

“I thought you said it didn’t work that way anymore.”

“Yes, because you left. Ozma was hitching the reins of that enchantment to the magic of your youth and energy. You were powering, like a generator, the immortality of Oz. You can’t understand what a profound effect it had on the merry old Land.”

“I had no idea,” said Dorothy.

“For everything that happened to you in Kansas City, something happened here in Oz.” He paused and took a sip of tea. “Not all of it good.”

“Such as?”

“Back when you were working at the shoe store, a job you loathed if my spies were correct, you met a young man who also worked in the store. On your lunch hours you would go down to the store’s basement, into a small alcove behind the oil burner, and in total darkness you would kiss. Every time you kissed, one of the Citizens of China Plate Land here in Oz shattered, and when first his hand found

a way into your undergarments, scores of children abruptly died in Quadling Country.”

She tried to stand, but as she rose, he reached out and gently touched her shoulder. She sat back into the chair.

“When your wealthy husband cheated on you, that, my dear, was calamitous. Your shame inspired that fiery ball of a Head out there, that roiling cloud of snarling electricity, to break from its moorings and fly out over the Land, Citizens and cattle disintegrating in its maw. It took all the humbug in Oz to get it back under my control. But even that time held no candle to your quiet later years. Secretary at a shoe factory. Fifteen long years of monotony, and oh how that dimmed the colors of Oz and made its magic stupid.”

She pulled the gun.

The Wizard took a sip of tea and laughed.

“Where are the Munchkins?” she said.

“Those ungrateful troglodytes deserted me.”

“Did they flee to Gillikin Country?”

“I’ll tell you where they are. They’re out in the Deadly Desert, no doubt turned to leather stone, seized as if crawling, hands outstretched, fingers frozen only inches from those of the fossils from Kansas and Nebraska. Why did you leave?”

Her gun hand trembled. “I didn’t want to be eleven forever. I spent four years here as an eleven-year-old living on my own. The last I was truly happy was when Aunt Em and Uncle Henry came to stay for a while. Do you remember how I showed them around? Before they left to return to Kansas, Aunt Em drew me aside one day and whispered in my ear, ‘You’ve got to get out.’ That was all she said. It made me wonder what twelve would be like.”

“What’s the gun for, if I might ask?”

“I’m going to shoot you.”

“I see,” he said. He winced and turned away from the barrel. “Now that you’ve used me up, before you do what you will, I beg you to tell me what happened in the last years. My spies deserted me along with the others some time ago.”

“That secretary job went on and on, and then one day, Mr. Steers, my boss, called me into his office. Sitting there in front of his desk was a young blond woman, very pretty. I hated her instantly. Her smile was like the Nome King’s. Mr. Steers motioned for me to take the chair next to this woman, and he introduced us. Her name was Edna. She would be his second secretary. I would be in competition with her for two months, and whichever one of us did better would get the job I’d already had for years.

“I worked so diligently—late nights, early mornings. She came late every day, and then he would call her into his office for, as he always said loud enough for the rest of the office staff to hear, ‘dictation.’ Once I put my ear to the door when they were in there and heard her grunting and him calling out to the Lord. I could already see the outcome of the competition. Of course I was laid off. The day I left, Steers called me into his office. Edna was sitting close to him, preparing to take dictation. He reached into his pocket and threw two crumpled twenty-dollar bills on his desk. ‘Nice knowing you,’ he said. I scooped up the money and left. With it, I bought this gun.

“Two nights later, I followed them to the local theater and sat three rows back from them in the dark, watching

The Lost Weekend

, starring Ray Milland and Jane Wyman. When the movie was over, I let them leave first. I kept my face in my box of popcorn, and they never noticed me. I eventually followed. As they strolled down the street to where Steers had parked, I picked up my step and passed them, walking fast. I had my hair up under a hat, and I was dressed in clothes I’d never have worn to the office. Once I got a few feet in front

of them, I turned, lifted the pistol, and pulled the trigger. The bullet went right into his left eye. He screamed, and I put one in his throat. Blood burbled out and he dropped.

“Edna took off running in her high heels. I caught her by her long blond hair and jerked her head back. She made a sound like the pigs did under the slaughter knife on Aunt Em and Uncle Henry’s farm. I shot her twice in the ass to take the fight out of her, and then I gave her two in the back of the head. She was on the ground but still twitching when I took to the alleys. I made it back to my place just in time. As I slipped the silver shoes on and stored the pistol in my briefcase, the police cars pulled up in front of my building. The cops were running up the stairs when I called out for Oz, and I was gone by the time they burst through the door.”

“Harrowing,” he said.

“Believe me, I enjoyed it.”

“Tsk-tsk,” said the Wizard. “Did you never know happiness back in the world? Not even for a few minutes? You were married for a full decade. What about love?”

“My husband was wealthy from wheat futures. We had everything, but everything in Kansas was like a box of broken toys compared to Oz, where one of my best friends was a fellow with a pumpkin for a head, and all our adventures ended brilliantly.”

“Did you love your husband?”

Dorothy cocked the trigger and brought her other hand up to steady her aim. “How could we be in love? I was daydreaming about Oz, and he was daydreaming about money. When the bottom fell out of the wheat market, when the country was turned to dust by his greed and his dreams rotted in a matter of days, he grew so angry. He took his rage out on me. When Toto came to my defense, barking and maneuvering to get between us, he beat the poor dog to

death with his cane. Not long after, he leaped to his death from the widow’s walk atop the mansion.”

“Leaped?” said the Wizard and cocked an eyebrow.

“He was a runtish man with a bad leg,” said Dorothy. “A good shove was all it took. His lawyers threatened to implicate me, and for their silence I forfeited whatever was left after the market crashed.”

“And how is this all my fault?”

“Because you’re the secret humbug behind it.”

“Preposterous,” he said and stood up.

Dorothy pulled the trigger twice, but there were no blasts from the gun. No bullets emerged, just two small black moths, which fluttered from the barrel and lazily wove their way toward the ceiling. She dropped the pistol on the table and stared as if in shock. “Oz is hell, isn’t it?” she screamed.

The Wizard laughed so hard his stomach shook and his cheeks grew red. As his glee subsided, he clapped his hands and whistled.

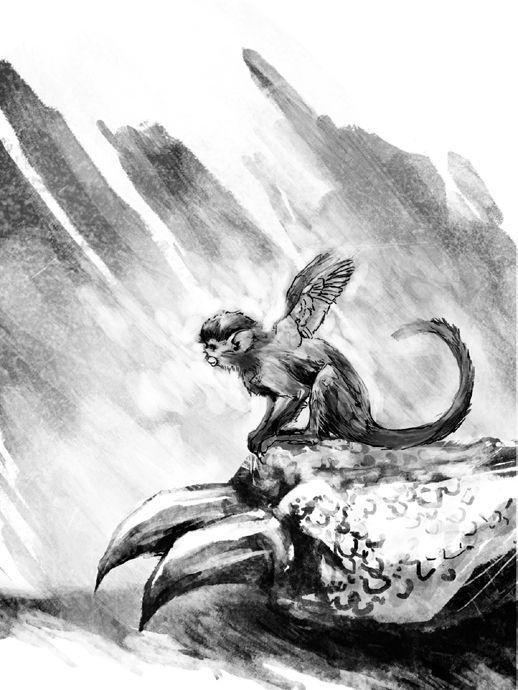

Dorothy, trembling, turned in her chair to see a half dozen Winged Monkeys gallop into the room through the curtained entrance. They snarled and spit and barely stood at bay, awaiting the Wizard’s command.

“Fly her out to the middle of the Deadly Desert and drop her,” he commanded.

She leaped from the chair, but they were already on her, their hairy knuckled fingers clamping her arms and legs. Their brutal faces in hers. The stink of them swirled with the action of their wings and made her weak.

“Here’s one adventure that won’t end brilliantly,” he said to her. “Fly!” he commanded.

The pack of growling creatures swept her toward the exit. Dorothy whimpered, and as she fainted, she heard the Wizard say, “There’s no place like home.”

BY JONATHAN MABERRY

-1-

“I

need a pair of traveling shoes.”

When the cobbler heard the voice, he peered up over the tops of his half-glasses, but there was no one there. The counter that separated him from the rest of the town square was littered with all the tools of his trade—hammers and scissors, awls and stout needles, glue and grommets. However, beyond the edge of the counter there was nothing.

Well, that was not precisely the case, because beyond the empty space that was beyond the counter were a thousand chattering, noisy, moving, bustling, shopping, buying, selling, yelling, laughing people. They were there in all the colors of the rainbow; green was the most common color here in the Emerald City, but the other colors were well represented, too. There were Winkies in a dozen shades of yellow; Munchkins in two dozen shades of blue; Quadlings in scarlets and crimsons and tomato reds; and Gillikins in twilight purples and plum purples and the purple of ripe eggplants.

But there was no one who seemed to own the tiny voice that had spoken.

The cobbler set down the boot he was repairing for a Palace guard.

“Hello?” he asked.

“Sir,” said the voice of the invisible person, “I need a pair of traveling shoes, if you please.”

“I do indeed please,” said the cobbler, “or I would if I could see your feet or indeed any part of you. Though, admittedly, your feet are necessary to any further discussion on the matter of shoes, traveling or otherwise.”

“But I’m right here,” said the voice. “Can’t you see me at all?”

The cobbler stood up and leaned over, first looking right and then looking left and finally looking down, and there stood a figure.