Pandora's Keepers (72 page)

Authors: Brian Van DeMark

———.

Science and Government

. Harvard University Press, 1961.

———.

Variety of Men

. Scribner’s, 1967.

Stern, Philip M., with Harold P. Green.

The Oppenheimer Case: Security on Trial

. Harper and Row, 1969.

Strout, Cushing. “The Oppenheimer Case: Melodrama, Tragedy, and Irony.”

Virginia Quarterly Review

, Spring 1964, 268–280.

Szasz, Ferenc Morton.

The Day the Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945

. University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Wang, Jessica.

American Science in an Age of Anxiety: Scientists, Anticommunism, and the Cold War

. University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Weart, Spencer R.

Nuclear Fear: A History of Images

. Harvard University Press, 1988.

———.

Scientists in Power

. Harvard University Press, 1979.

Weiner, Charles. “A New Site for the Seminar: The Refugees and American Physics in the Thirties.” In

The Intellectual Migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960

, edited by Donald Fleming and Bernard Bailyn. Harvard University Press, 1969.

Williams, Robert Chadwell.

Klaus Fuchs: Atom Spy

. Harvard University Press, 1987.

Wyden, Peter.

Day One: Before Hiroshima and After

. Simon and Schuster, 1984.

York, Herbert F.

The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller, and the Superbomb

. W.H. Freeman, 1976.

Zachary, G. Pascal.

Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century

. Free Press, 1997.

Zuckerman, Solly. “Nuclear Wizards.”

New York Review of Books

, March 31, 1988, 26–31.

Brian VanDeMark teaches history at the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis. He has lectured throughout the world, including at Oxford, where he was a Visiting Fellow at St. Catherine’s College and the Rothermere American Institute. He coauthored Robert S. McNamara’s #1 bestseller,

In Retrospect

, and assisted Clark Clifford with his bestseller,

Counsel to the President

. His

Into the Quagmire

, published by Oxford University Press, is one of the classic works on Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam.

*

The value of c

2

—the square of the speed of light—is 100,000,000,000,000,000,000.

*

The NDRC became the OSRD in June 1941.

*

Evidence has recently come to light suggesting that Oppenheimer was an “unlisted” member of a Communist Party cell at Berkeley into the early 1940s. No concrete evidence has emerged, however, that he ever committed espionage against the United States on behalf of the Soviet Union. See Jerrold and Leona Schecter,

Sacred Secrets: How Soviet Intelligence Operations Changed American History

(Brassey’s, 2002), pp. 316–17; and Herken,

Brotherhood of the Bomb

, pp. 31–32, 54–57, 111, 251, 289, 340–41.

*

Teller’s security clearance was expedited at the specific request of Oppenheimer, whose own clearance would be withdrawn a decade later as a result of hearings at which Teller testified as a key witness against him. See chapter ten, pp. 275–279.

*

Sherwin,

A World Destroyed

, p. 163. The Interim Committee had seven members: Stimson, as chairman (with his special assistant George Harrison as deputy); Ralph Bard, an undersecretary, representing the Navy Department; Will Clayton an assistant secretary, from the State Department; experienced scientific administrators Vannevar Bush, James Conant, and Karl Compton; and James Byrnes, as Truman’s personal representative.

*

The USSR successfully tested its first atomic bomb in late August 1949. See chapter 9, p. 219.

*

Policy makers also indulged in self-deception. Stimson told Truman on May sixteenth: “I am anxious to hold our Air Force, so far as possible, to the ‘precision’ bombing which it has done so well in Europe. I believe the same rule of sparing the civilian population should be applied, as far as possible, to the use of any new weapons.” (Henry L. Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University.) Truman, for his part, insisted to the end of his life that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were directed against “military” targets.

*

In fact, the Franck Report stated: “The saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and by a wave of horror and repulsion sweeping over the rest of the world.”

*

Fermi came to resent Compton’s (if not Oppenheimer’s) pressure that night. When a colleague complained to Fermi a few years later, “Why does [Compton] talk so much these days about God and philosophy and brotherhood?” Fermi replied acidly, “Current need. What did the country need most during the war? The Bomb. What does it need now? Religion.” (Quoted in Davis,

Lawrence and Oppenheimer

, p. 249.)

*

The U-235 for the Hiroshima bomb was transported to Tinian by the cruiser

Indianapolis

as a safety precaution. Whereas the plutonium for the Nagasaki bomb was the output of about two weeks’ production at Hanford by the summer of 1945, the uranium bomb was the output of about six months’ production at Oak Ridge. Consequently, Washington did not want to risk losing it by transporting it by plane, which might crash or be shot down. Three days after delivering the U-235 to Tinian, the

Indianapolis

was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine en route to the Philippines, sinking in less than half an hour and taking the lives of nearly one thousand American sailors.

*

The Big Three summit conference outside Berlin was attended by Truman, Churchill, Attlee, and Stalin in late July 1945.

*

Other members of the committee were Vannevar Bush, James Conant, Leslie Groves, and Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy. The committee’s consultants—in addition to Oppenheimer—were former Tennessee Valley administrator David Lilienthal, New Jersey Bell president Chester Barnard, General Electric vice president Harry Winne, and Monsanto executive Charles Thomas.

*

Russian scientists were well along toward a bomb of their own, due in part to the espionage of Western scientists such as Klaus Fuchs, Theodore Hall, and Allan Nunn May (and perhaps others), whose spying simplified and sped their work.

*

This is why the superbomb also became known as the hydrogen or H-bomb.

*

The GAC in 1949 also included James Conant; Lee DuBridge, leader of the wartime radar lab at MIT and now president of Caltech; Hartley Rowe, an engineer who had worked on materials procurement for the Manhattan Project; Oliver Buckley, president of Bell Telephone Laboratories and an expert on guided missiles; Glenn Seaborg, discoverer of plutonium and coauthor of the 1945 Franck Report; and Cyril Smith of the University of Chicago, who had been in charge of the metallurgy division at Los Alamos during the war.

*

One GAC member, Glenn Seaborg, was abroad on a visit to Sweden. The GAC had his views, however, in the form of a letter. Seaborg reluctantly supported development of the superbomb.

*

David Lilienthal, chairman; financier Lewis Strauss; attorney Gordon Dean; and Princeton physicist Henry Smyth. The fifth AEC commissioner, businessman Sumner Pike, did not attend.

*

Sakharov’s disclosure made the effort of Oppenheimer and others to prevent an escalation of the nuclear arms race appear “hopeless” in retrospect, concluded Hans Bethe, reasoning that “Stalin would never have accepted an agreement

not

to develop the H-bomb.” (Notes, “TV 1995—Anniversary,” Hans Bethe Personal Papers.)

*

Former State Department official Alger Hiss was convicted of perjury on January twenty-first for having denied passing secret documents to Soviet agent Whittaker Chambers during the 1930s. On February third, Klaus Fuchs was publicly arraigned in Britain for atomic espionage during the war. Exploiting these sensational developments, Republican senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin began an anticommunist witch-hunt on February ninth with a speech in which he claimed to have a list of 205 communists working in the State Department.

*

They were right. The Soviets tested their first superbomb, a fission-boosted weapon, on August 12, 1953. Their first “true” superbomb, based on thermonuclear fusion, was tested on November 22, 1955.

*

Bethe and Fermi subsequently consulted at Los Alamos on the superbomb’s development, and Bethe helped design the weapon based on an idea conceived by Edward Teller, Stanis-law Ulam, and Richard Garwin.

*

The FBI monitored these and subsequent conversations between Oppenheimer and his lawyers, violating the attorney-client privilege and giving Strauss and the AEC the unfair advantage of anticipating Oppenheimer’s defense.

*

Teller had told FBI investigators in 1950 that Frank Oppenheimer would not have joined the Communist Party without the “tacit approval” of his brother. (See SAC, WFO to FBI Director, “Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer,” January 5, 1954, FBI J. Robert Oppenheimer Serial File [100–17828]/Freedom of Information Act Files.)

*

If Oppenheimer did lie about his Communist Party affiliation in the late 1930s and early 1940s, why did he do so? Most likely because he felt vulnerable in the anticommunist political climate of the 1950s and thought it necessary to cover up his now embarrassing past in order to maintain his influence as a government adviser, which had become so important to him after 1945 as a way of assuaging his guilt over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One who knew Oppenheimer well during his radical days offered a revealing insight: “This fiction that he was putting forward was presumably necessary for his protection in the carrying out of an ideal purpose which I had no doubt he was pursuing.” (Chevalier,

Oppenheimer

, p. 84.)

*

Paradoxically, the implications of Oppenheimer’s false story were more serious than what actually happened. His story impeded army security officers, hurt his friend Chevalier, and damned himself in the eyes of both his friend and his judges. To protect others, Oppenheimer accepted the guilt of a made-up story that he could not sustain.

*

Jean Tatlock committed suicide the following year.

*

Groves later said that he had compelled Oppenheimer to divulge Chevalier’s identity only to stop complaints from his security officers.

*

Shortly before Szilard died, he said that he wanted his ashes tied to a helium balloon and sent skyward. People, he said, should look up rather than down. But—as had been the case with so many of Szilard’s ideas—without him there to fight, pester, and promote, nothing happened. His ashes, kept in a California crematory after his death, would finally be buried during the centenary of his birth in 1998.

*

Teller was later proved quite wrong. In 1963 the United States led the Soviet Union by a large margin in both nuclear technology and stockpiled nuclear weapons.

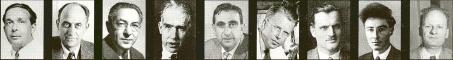

THEY WERE NINE BRILLIANT MEN

who believed in science and who saw before anyone else the awesome workings of an invisible world. They came From many places, some fleeing Nazism in Europe, others quietly slipping out of university teaching jobs, all gathering in secret wartime laboratories to create the world’s first atomic bomb.

During World War II, few of the atomic scientists questioned the wisdom of their desperate endeavor. But afterward they were forced to deal with the sobering legacy of their creation. Some were haunted by the dead of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and became anti–nuclear weapons activists; others went on to build even deadlier bombs, In explaining their lives and their struggles, Brian VanDeMark superbly illuminates not only their moral reckoning with their horrific creation but also the ways in which each of us grapples with responsibility and unintended consequences.

“The story of the Manhattan Project is famous, and so are the complicated, remarkable men behind it, whom VanDeMark brings engrossingly to life: men like Oppenheimer, Bethe, Bohr, Teller, Fermi, and Szilard…. VanDeMark does not overlook the implications in today’s world.”

—

Publishers Weekly

(starred review)