PARIS 1919 (54 page)

24. The Turkish delegation to Lausanne in 1922â23. General Ismet, walking stick in hand, was Atatürk's trusted representative; he drove Curzon to distraction with his refusal to budge from his negotiating position.A treaty was eventually signed in 1923 that left Turkey in its present form.

25. The Peace Conference drew up treaties with the defeated powers of Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary and Ottoman Turkey, but that with Germany proved difficult. Because of disagreements among the Allies, what was to have been a preliminary meeting before negotiating with the enemy gradually turned into the Peace Conference proper. The German terms were not ready until May 1919. Count Ulrich Brockdorff-Rantzau (

third from

right

) was Germany's foreign minister and leader of its delegation.The Germans never forgave the Allies for simply imposing their terms and declining to negotiate seriously.

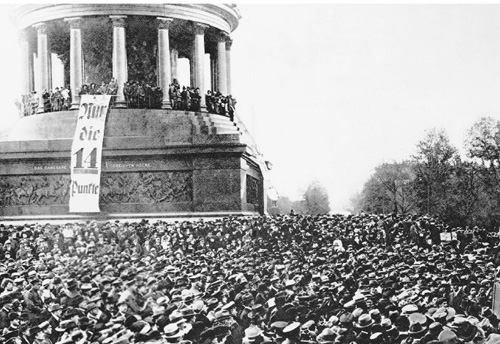

26. An enormous protest demonstration in Berlin.The Germans were horrified by the peace terms, which they saw as a betrayal of a pledge they felt they had received from the Allies at the time of the armistice: that the peace would be negotiated on the basis of Wilson's new diplomacy, with no unjust retribution.The banner demands “Only the Fourteen Points,” a reference to Wilson's famous speech.

27. The peacemakers made only a few minor changes in the terms in response to German objections and comments.They also gave the German government a deadline for signing, which plunged Germany into a political crisis. In Paris, Allied preparations for either the signing of the treaty or a resumption of the war went ahead. Here, French soldiers move furniture at the great palace at Versailles in preparation for the signing.

28. On June 23, 1919, shortly before the Allied deadline expired, the German government finally agreed to sign.The ceremony was scheduled for June 28 and there was a scramble for tickets. Some of those who could not get into the Hall of Mirrors were forced to peer through the windows.

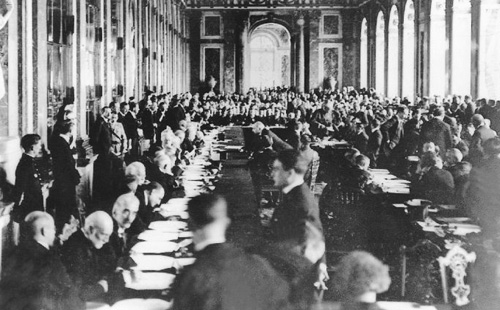

29. The scene inside the Hall of Mirrors as the Treaty of Versailles was signed. The location had great significance for the French because it was here that the new nation of Germany had been proclaimed after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870â71.

“Throughout the whole of my negotiations with the Italians,” Lloyd George recalled, “I found that their foreign policy was largely influenced by a compound mixture of jealousy, rivalry, resentment, but more particularly, fear of France.”

23

For France it was not so much a matter of fear (although there was some concern over the Italian birthrate) but of condescension tinged with contempt.

In December 1918, after the Allied meetings in London, Orlando and Sonnino had traveled to Paris with Clemenceau. “We did not see them a single time in the course of the long journey,” reported Clemenceau's aide, “and, at the Gare du Nord, they disappeared without taking leave of M. Clemenceau, who was not only quite astonished but even quite offended.” Clemenceau had a grudging respect for Sonnino but little use for Orlando: “all things to all men, very Italian.”

24

The collapse of Austria-Hungary opened up fresh areas for rivalry as France and Italy competed for influence in the center of Europe. In the Adriatic, France was torn between befriending Yugoslavia and keeping on reasonable terms with Italy. “I am so bored with Adriatic matters,” wrote a French diplomat. “All the same we shouldn't abandon the Yugoslavs. They are as unreasonable as these others, but they are weak. How stupid they are in Rome!” As Clemenceau said wearily one day, much to Orlando's indignation, “My god, my god! Italy or Yugoslavia? The blonde or the brunette?” By April 1919 Clemenceau had gone firmly for the brunette. He was furious that the Italians had not supported France over the Saar or the issue of trying Germans for war crimes. He also took for granted that he had room to maneuver because, in the end, Italy would have to remain friendly to France.

25

Orlando and Sonnino, suspicious of their allies, hostile to their Yugoslav neighbor and caught in an uneasy alliance which neither dared break for fear of bringing their government down, plowed on. Like a bomb with a slow-burning fuse, the official Italian memorandum went to the Peace Conference on February 7. It is an interesting document which, although it scarcely mentions the Treaty of London, repeats its provisions virtually unchanged, decked out this time in the ill-fitting clothes of the new diplomacy. “The Italian claims,” it started, “show such a spirit of justice, right-fulness, and moderation that they come entirely within the principles enunciated and approved by President Wilson and should therefore be recognised and approved by everybody.” Italy's demands were based almost entirely on self-determination, for Italians of course; the few small instances where it claimed land inhabited by other peoples were solely to make secure borders.

26

Orlando and Sonnino concentrated, to the dismay of their own colonialists, on Europe. The Italian Colonial Ministry had thrown itself enthusiastically into preparing grand schemes, particularly for Africa. For Italian nationalists, the “year of shame” of 1896, with the defeat at Aduwa, could be wiped out only by conquest. Britain and France must stand aside, the colonial minister, Gaspare Colosimo, urged his government, and allow Italy to have exclusive influence over Ethiopia. Furthermore, in order to cement Italy's control over the routes from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean into Ethiopia, Britain should add its share of Somalia to the piece already in Italian hands and hand over the northeast part of Kenya. France should relinquish its tiny piece of Somalia, as well as the railway from the port of Djibouti into Addis Ababa. Colosimo also dreamed of a Libya enlarged by territory from British-run Egypt and from French possessions and, if the Portuguese colonies went begging, of acquiring Angola as well. Just before the end of the war he sent a memorandum to Balfour and House outlining these goals. The wording was carefully chosen to sound Wilsonian; the impact, however, was to leave an impression of Italian greed.

27

Orlando and Sonnino were not prepared to push the African claims strongly in Paris and it is unlikely that Britain and France would have paid much attention. They briskly divided up the German colonies without consulting Italy and, as for handing over their own territory to Italy, each country expressed itself perfectly willing to do so as long as the other did. The Italians were left with yet another grievance and yet another frustrated dream.

28

Mussolini subsequently found that useful.

In Europe, the only one of Italy's claims that was settled easily was for a piece of Austria-Hungary south of the Brenner Pass, the South Tyrol and below that the Trentino. The Trentino, which was largely Italian-speaking, was not a problem, but the Tyrol was overwhelmingly German. The Tyrolese protested at the partition of a province with a long history of self-government. So did the government of the new state of Austria: “It is actually the Tyrol, till now, except Switzerland, the most burning centre of liberty and resistance to all foreign domination, which will be sacrificed to strategic considerations, as an offering on the altar of militarism.” The Italians argued that Italy could be safe only if it held the land sloping up to the Brenner Pass. “Any other boundary to the south would merely be an artificial amputation entailing the upkeep of expensive armaments contrary to the principles by which Peace should be inspired.” Wilson, perhaps to show the Italians that he could be reasonable, let them know before the Peace Conference opened that he would not object to the change in Italy's northern frontier. His fellow peacemakers acquiesced. Lloyd George briefly worried about the Tyrol, according to House, because he had once been on holiday there and it was one of the few parts of the continent he knew well. Wilson later regretted that he had handed over so many German-speaking Tyroleseâ250,000 of them, to Italian rule. So did they, especially after 1922, when the Fascists decided to make them Italian. Suddenly, schools and government offices were run in Italian; children could not be given names that “offended Italian sentiment.” It was only in the vastly changed Italy and Europe of the 1970s that the Tyrol finally regained some of its old autonomy.

29