Pat Boone Fan Club

“Silverman’s language is, by turns, blunt, wrenching, sophisticated, lyrical, tender, hilarious. She writes with wicked dark humor, splendid intelligence, wry wit, and honest confrontation. There’s no other book quite like it.”

—Lee Martin, author of

From Our House

and

Such a Life

“Reading

The Pat Boone Fan Club

feels like sitting down for coffee with a long-lost friend. Silverman reveals the heights that skillful and innovative memoir can achieve.”

—Hope Edelman, author of

Motherless Daughters

“Filled with warmhearted humor and profound compassion, this tour de force exploration of the search for identity is a joy to behold.”

—Kaylie Jones, author of

Lies My Mother Never Told Me

“Silverman is the Tennessee Williams of memoir.”

—Robert Vivian, author of

The Least Cricket of Evening

The Pat Boone Fan Club

American Lives

Series editor:

Tobias Wolff

The Pat Boone Fan Club

My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew

Sue William Silverman

University of Nebraska Press

Lincoln and London

© 2014 by Sue William Silverman

Acknowledgments for the use of copyrighted material appear in “

Acknowledgments

,” which constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

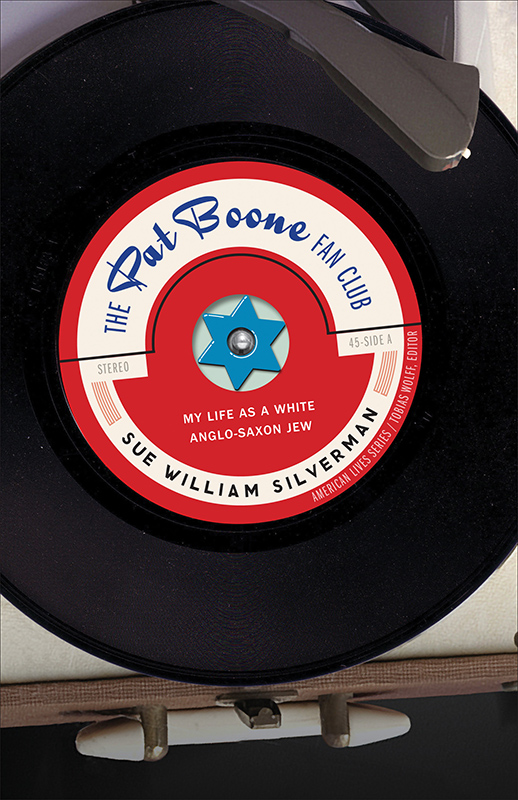

Front cover image Turntable © sabatex/iStockphoto.com; 45 © caspari/iStockphoto.com.

Author photo courtesy of the author.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Silverman, Sue William.

The Pat Boone fan club: my life as a white Anglo-Saxon Jew / Sue William Silverman.

pages cm.—(American lives)

ISBN

978-0-8032-6485-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN

978-0-8032-6498-4 (pdf)

ISBN

978-0-8032-6499-1 (epub)

ISBN

978-0-8032-6500-4 (mobi)

1. Silverman, Sue William. 2. Jews—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish women—United States—Biography. 4. Jews—United States—Identity. 5. Jewish women—United States—Identity. 6. Boone, Pat—Appreciation. I. Title.

E

184.37.

S

55

A

3 2014 973'.04924—dc23

2013034570

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

for Marc Sheehan, my Irish mensch

for Dr. Donald Moss who sees . . . and who teaches me to see

Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self: in which case, it is best that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which one’s nakedness can always be felt, and, sometimes, discerned. This trustin one’s nakedness is all that gives one the power to change one’s robes.

James Baldwin

Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long-shot.

Charlie Chaplin

Take my hand and walk this land with me . . .

Pat Boone, lyrics to “Exodus”

Acknowledgments

I am honored to have Kristen Elias Rowley as my editor at the University of Nebraska Press. I am also extremely grateful to Marguerite Boyles, Martyn Beeny, Kyle Simonsen, Andrea Shahan, Laura Wellington, Alison Rold, Emily Giller, Joy Margheim, and all the other talented people at the press.

A heartfelt thanks to Peggy Shumaker and Lee Martin for their support, friendship, and wisdom.

Profuse thanks to the faculty and students at Vermont College of Fine Arts who listened to me read much of this material in earlier drafts.

Several sections in this book, often in different forms, previously appeared in the following publications. Many thanks to the judges and editors who supported my work.

“The Pat Boone Fan Club.”

Arts & Letters: Journal of Contemporary Culture

(Spring 2005). Also selected for the second edition of

The Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Nonfiction: From 1970 to the Present

(Simon and Schuster, 2007).

“Galveston Island Breakdown: Some Directions.” Winner, Brenda Euland Prose Prize,

Water~Stone Review

, Fall 2006; judge: Nicholas DelBanco. Received special mention, Pushcart Prize

XXXII

: Best of the Small Presses, 2008.

“That Summer of War and Apricots.” Winner,

Mid-American Review

essay contest, 2006; judge: Josip Novakovich.

“The Wandering Jew” (originally titled “Tramping the Land of Look Behind”). Winner,

Hotel Amerika

essay contest, Spring

2006. Received notable essay citation,

The Best American Essays

, 2006.

“I Was a Prisoner on the Satellite of Love.”

River Teeth: A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative

(Spring 2006).

“Concerning Cardboard Ghosts, Rosaries, and the Thingness of Things.”

Prairie Schooner

(Spring 2007).

“See the Difference.”

Silence Kills: Speaking Out and Saving Lives

, ed. Lee Gutkind (Southern Methodist University Press, 2007). Nominated for a Pushcart Prize, 2007.

“Prepositioning John Travolta.”

Ninth Letter

(Fall/Winter 2011–12). Nominated by the Pushcart Board of Contributing Editors for a Pushcart Prize, 2011.

Quotes in “I Was a Prisoner on the Satellite of Love” are from episodes of

Mystery Science Theater 3000

, created and produced by Best Brains, Inc., Eden Prairie

MN

.

The inspiration for “An Argument for the Existence of Free Will and/or Pat Boone’s Induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame” (a work of the imagination) is

Superman’s Girlfriend, Lois Lane

, no. 9 (May 1959), National Comics Publications, Inc. Some quotes from Pat Boone are from Pat Boone’s

America, 50 Years: A Pop Culture Journey through the Last Five Decades

(

B&H

Publishing Group, 2006).

This is a work of creative nonfiction. Since every experience has different points of view, some people might remember events differently. These, in compressed time and in nonchronological order, are my memories, recollected to the best of my ability. Some names and details have been changed to protect people’s privacy.

The Pat Boone Fan Club

Dear Gent[i]le Reader,

Friends, Christians, Lundsmen, Lend me your Souls (Lost or otherwise). I come not to Malign or Bury (nay Besmirch) my Fellows, but, like Wayward or Wandering Jews Everywhere, to Seek that which is most Holy: A Birthright. I Strayed Far from my Heritage, my People, and Now I ask you, Gentile And Jew Alike:

Am I Still a Jew? And if not, then What? Or Who?

I Pray Thee, Dear Reader, whoever you are, do not avert your eyes as if I am Unclean or Traitorous based on the Title or Subtitle of this Unfortunate Saga. Show but a modicum of Pity. After being cast out from my Tribe, or so I felt (or was it Destiny? Fate?), I stumbled Hither and Yon—a one-Jew Diaspora.

I labored to discover Knowledge, Identity, Enlightenment, all Faithfully Rendered In this Document. I, Poor Pilgrim, Beseech Thee: Turn these Pages. Understand.

In short, Dear Reader, after Perusing my Tale of Farce and Woe, I Hope, most Fervently, to Hear You Call my Name in Welcome, offering Respite. For I Spent long Vagabond years as a Gefilte Fish Swimming Upstream with Nary a Fin . . . a Sorrowful, Utterly Lost and Sad Little Gefilte, far from her Glass Jar.

A Gefilte Without A School. A Gefilte Without a Home.

How Desperately I Swam against the Current (as have Not We All, Gentle Reader, whether Fish or Foul [

sic

]) Seeking a Place of Comfort to Rest my Weary Soul.

Your Most Humble Servant,

S.W.S.

The Pat Boone Fan Club

Pat Boone dazzles onto the stage of the Calvary Reformed church in Holland, Michigan. He wears white bucks, white pants, a white jacket with red- and blue-sequined stars emblazoned across the shoulders. I sit in the balcony, seats empty in the side sections. I’m here by chance, by luck. Kismet. A few weeks ago I happened to see his photograph in the local newspaper, the

Sentinel

, announcing the concert—part of Tulip Time Festival—only twenty minutes from my house. I stared at his photo in alluring black and white, just as, back in junior high school, I gazed at other photos of him. I ordered a ticket immediately.

This less-than-sold-out crowd enthusiastically claps after the opening number, his big hit “Love Letters in the Sand.” But there are no whistles or shrieks from this mostly elderly, sedate, female audience. No dancing in the aisles, no mosh pit, no rushing the stage. If a fan swoons from her upholstered pew, it will more likely be from stroke than idolatry. The cool, unscented air in the auditorium feels polite as a Sunday worship service—rather than a Saturday-night-rock-and-roll-swaggering, Mick Jagger kind of concert.

Yet

I

am certainly worshipful. Of

him

. I am transfixed. Breathless . . . as if his photograph—that paper image—is conjured to life. I watch only him through binoculars, me in my own white jacket, as if I knew we’d match.

Pat Boone began as a ’50s and ’60s pop singer, though he has now aged into a Christian music icon favored by—I’m sure—Republicans. That I am a first-generation Russian American atheist liberal Democrat gives me no pause, not even as he per

forms in this concrete megachurch weighted with massive crosses. In fact, as I grew up these very symbols gave me comfort.

I’m not surprised he still affects me. During the days leading up to tonight’s concert, I plotted to meet him backstage. But in case I am too overwhelmed to speak, I’ve written a letter explaining the reason for my devotion. To further prove my loyalty, I’ve retrieved, from an old scrapbook, my “

SUE

IS

A

MEMBER

OF

THE

PAT

BOONE

FAN

CLUB

” card, printed on white stock. Surely the letter and card are all the credentials I’ll need to be waved past security, to grant me access to Pat Boone. Tonight I’m determined to finally tell him what I failed to say last time we met, years ago, when I got his autograph after attending one of his live television shows. Time collapses as if, even now, it’s not too late for him to save me from my Jewish family, save me from a childhood long ended.

I curled up on the baby-blue bedspread in my home in Glen Rock, New Jersey, a magnifying glass in my teenage hand. Slowly I scanned the glass across black-and-white photographs of Pat Boone in the latest issue of

Life

magazine. In one, he, his wife, Shirley, and their four young daughters perch on a tandem bicycle in front of their New Jersey home, not many miles from my own. I was particularly drawn to the whiteness in the photos. Pat Boone’s white-white teeth beamed at me, his white bucks spotless. I savored each cell of his being as I traced my finger across his magnified image. I believed I felt skin, the pale hairs on his forearms. Only a membrane of paper separated me from a slick fingernail, a perfectly shaped ear, the iris of his eye. Surely the wind gusted his hair, his family’s hair, but in the photograph all movement was frozen, the bicycle wheels stationary, never to speed away from me. The family itself pedaled in tandem, legs pumping in perfect, still arcs. It was this crisp, clean, unchanging certainty that I craved.

The hands on his wristwatch were stopped at 3:40. I glanced at my own watch, almost 3:40. I didn’t move, waiting for the minute hand to reach the eight, as if I could will time itself to stop, entranced by the notion that we would both endlessly exist in this same segment of time. For even as I tumbled inside the photograph, we remained static in this one moment, suspended at 3:40 . . .

. . . together. I sit on the tandem bike directly behind him, leaning toward him. Now inside the black-and-white photo, I see lilacs, maple trees, shutters on windows. But I’m not distracted by scents or colors. I don’t inhale the Ivory soap of his shirt, don’t sense warm friction of rubber beneath the wheels of the bike, don’t feel loss or know that seasons change.

My ponytail, streaming behind my back, is frozen, captured with him and his family—now

my

consistent and constantly loving family.

I fantasized living inside this black-and-white print, unreachable. This immaculate universe was safe, far away from my father’s all-too-real hands, hands that hurt me at night.

Through my bedroom window, sun glinted off the glass I held inches from Pat Boone’s face. Round magnifier. Beam of light. Halo. I placed my hand, fingers spread, beneath the glass, hovering just above the paper, as if glass, hand, photograph,

him

—all existed in disembodied, heavenly light.

The bus rumbled across the George Washington Bridge, over the Hudson River. I clutched a ticket to his television show in one hand, a copy of his book,

’Twixt Twelve and Twenty

, in the other. Silently, I sang the jingle “See the USA in Your Chevrolet,” with which he closed his weekly program—a show I watched religiously on our black-and-white Zenith. Now, with the darkness of New Jersey behind me, the gleaming lights of Manhattan before me, I felt as if I myself were a photograph slowly developing into a new life. In just an hour I would see him in person

.

I wanted to be with him—be his wife, lover, daughter, house

guest, girlfriend, best friend, pet. Interchangeable. Any one of these relationships would do.

Sitting in the studio during the show, I waited for it to end. Mainly, I waited for the time when we would meet. Yes, I suppose I loved his voice, his music. At least, if asked, I would claim to love his songs. What else could I say, since there was no language at that moment to specify what I most needed from Pat Boone? How could I explain to him—to anybody—that if I held that magnifying glass over my skin, I would see my father’s fingerprints? I would see skin stained with shame. I would see a girl who seemed marked by her very Jewishness. Since my Jewish father misloved me, what I needed in order to be saved was an audience with Pat Boone.

There in

that

audience, I was surrounded by teenage girls crying and screaming his name. But I was different from those fans. Surely he knew this, too, sensed my silent presence, the secret life we shared. Soon I no longer heard the girls, no longer noticed television cameras, cue cards, musicians. No longer even heard his voice or which song he sang. All I saw was his face suffused in a spotlight, one beam emanating as if from an otherwise darkened sky.

I queued up after the show, outside the stage door, with other fans. I waited with my Aqua Net flipped hair, Peter Pan collar, circle pin, penny loafers. The line inched forward, girls seeking autographs.

But when I reached him, I was too startled to speak. I faced him in living color. Pink shirt. Brown hair. Suede jacket. His tanned hands moved; his brown eyes actually blinked. I saw him

breathe

. I forgot my carefully rehearsed words:

Will you adopt me?

Besides, if I spoke, I feared he wouldn’t hear me. My voice would be too low, too dim, too insignificant, too tainted. He would know I was too distant to be saved. I felt as if I’d fallen so far from that photograph that my own image was out of focus. I was a blur, a smudged Jewish blur of a girl, mesmerized by a golden cross, an

amulet on a chain around his neck. I continued to stand, unmoving, speechless, holding up the line.

“Is that for me?” he finally asked, smiling. He gestured toward the book. I held it out to him. He scrawled his name.

Later, alone in my bedroom, lying on my blue bedspread, I trailed a fingertip over his autograph. I spent days tracing and duplicating it. I forged the name “Pat Boone” on all my school notebooks using black India ink. I wrote his name on my white Keds with a ballpoint pen. At the Jersey shore I scrawled my own love letters in the sand. But I had missed my chance to speak to him. My plea for him to save me remained unspoken.

Now, watching him through binoculars in the Calvary Reformed church in Holland, Michigan, I again scan every cell of his face, his neck. I’m sure I distinguish individual molecules in his fingers, palms, hands, wrists. He wears a gold pinkie ring, a gold-link bracelet. And a watch! That watch? I wonder if it’s the same 3:40 watch. In his presence I am once again tranced—almost as if, all this time, we’ve been together in a state of suspension.

He doesn’t even appear to have aged—much. Boyish good looks, brown hair. Yet this grandfather sings his golden oldies, tributes to innocence and teenage love: “Bernadine,” “Moody River,” “Friendly Persuasion,” “Tutti Frutti.” His newer songs reflect God and patriotism. Well, he sings, after all, to a white Christian audience, mainly elderly church ladies with tight gray curls, pastel pantsuits, sensible shoes. I know I am the only one here who voted for President Clinton, who wears open-toed sandals, who isn’t a true believer. But nothing deters me. I feel almost like that teenage girl yearning to be close to him. Closer.

He retrieves, from the piano, a bouquet of tulips wrapped in cellophane. He explains to the audience that at each concert he presents flowers to one young girl. He peers into the darkened auditorium, asking, half jokingly, whether any girls have actually attended the concert. “Has anyone brought their granddaughters?”

I glance around. In one section sits a tour group of older women all wearing jaunty red hats. At least twenty of these hats turn in unison, searching the audience. No one else moves. The row in front of me seems to be mother-and-daughter pairs, but most of the daughters wear bifocals, while some of the mothers, I noticed earlier, used canes to climb the stairs. After a moment of silence, Pat Boone, cajoling, lets us know he found one young girl at his earlier, four o’clock show. He lowers the microphone to his side, waiting.

Me. I want it to be me.

A girl, her neck bent, silky brown hair shading her face, finally walks forward from the rear of the auditorium. Pat Boone hurries down the few steps, greeting her before she reaches the stage. He holds out the flowers, but she doesn’t seem to realize she’s supposed to accept them.

“What’s your name?” he asks.

“Amber.” She wears ripped jeans and a faded sweatshirt.

“Here.” Again he offers her the tulips. “These are for a lovely girl named Amber.” This time she takes them.

Strains of “April Love” flow from the four-piece band. His arm encircles her waist. Facing her, he sings as if just to her, “April love is for the very young . . .” The spotlight darkens, an afterglow of sunset. The petals of the tulips, probably placed onstage hours earlier, droop.

After the song, Pat Boone beams at her and asks for a kiss. “On the cheek, of course.” He laughs, reassuring the audience, as he points to the spot. The girl doesn’t move. “Oh, please, just one little peck.” His laugh dwindles to a smile.

I slide down in my seat. I lower the binoculars to my lap.

Kiss him

, I want to whisper to the girl, not wanting to witness Pat Boone embarrassed or disappointed.

No, walk away from him.

Because he’s old enough to be your father, your grandfather.

Instead, he bends forward and brushes his lips on her cheek. She escapes down the aisle to her seat, the bouquet held awkwardly in her hand.

The lights onstage are extinguished. His voice needs to rest, perhaps. Images of Pat Boone in the Holy Land flash on two large video screens built into the wall behind the pulpit, while the real Pat Boone sits on a stool. The introduction to the theme song from

Exodus

soars across the hushed audience. Atop the desert fortress Masada—the last outpost of Jewish zealots who chose mass suicide rather than Roman capture—a much younger Pat Boone, in tan chinos, arms outstretched, sings, “So take my hand and walk this land with me,” lyrics he, himself, wrote. Next the video pans to Israelis wearing kibbutz hats, orchards of fig trees, the Sea of Galilee, Bethlehem, the Old City in Jerusalem. The Via Dolorosa. The Wailing Wall. The Dead Sea.

“Until I die, this land is mine.”

A final aerial shot circles a sweatless and crisp Pat Boone on Masada. Desert sand swelters in the distance.

This land is mine . . .

For the first time I wonder what he means by these words he wrote. Does he mean, literally, he thinks the Holy Land is his, that it belongs to Christianity? Or perhaps, is he momentarily impersonating an Israeli, a Zionist, a Jew? Or maybe this appropriation is just a state of mind.

Pat Boone, Pat Boone. Who are you? I always thought I knew.

The lights flash on. Pat Boone smiles. The band hits the chords as he proclaims we’ll all have “A Wonderful Time up There,” a song with which I’m familiar.

I’ve always been more attuned to Christian songs than those of my own religion. I frequented churches over the years, immersing myself in hymns and votive candles. Once I even owned a garnet rosary, magically believing this Catholic amulet offered luck and protection. At only one period in my life, in elementary

school, when I lived with my family on the island of St. Thomas, in the West Indies, did I periodically attend Jewish services.

We drove up Synagogue Hill some Saturday mornings, parking by the wrought-iron gate leading to the temple. We entered the arched stucco doorway, where my father donned a yarmulke. The air cooled, shaded from tropical sun. In my best madras dress, I followed my parents down the aisle, the floor thick with sand. My feet, in buffalo-hide sandals, etched small imprints behind the tracks left by my father’s heavy black shoes. I sat between my parents on one of the benches. The rabbi, standing before the mahogany ark containing the six Torahs, began to pray. I slid from the bench to the sandy floor.

The sand was symbolic in this nineteenth-century synagogue, founded by Sephardic Jews from Spain. During the Spanish Inquisition, Jews, forced to worship in secret, met in cellars where they poured sand on floors to muffle footsteps, mute the sound of prayers. This was almost all I knew of Judaism except stories my mother told me about the Holocaust when bad things happened to Jews—even little Jewish girls.