Peace Work (13 page)

Authors: Spike Milligan

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Humor & Entertainment, #Humor, #Memoirs

Lieutenant Priest seeks me out. Tomorrow Bill Hall and I are to report to Villach Demob Camp to be issued with civilian clothes, how exciting! Next morning a 15

cwt

truck takes us to the depot. Giant sheds loaded with military gear. We hand in our papers and discharge sheets, then we are given the choice of three suits – a grey double-breasted pinstripe suit, a dark blue ditto or a sports jacket and flannels. This photograph shows us with our chosen clobber.

Goodbye Soldier! Bill Hall, unknown twit and Spike.

I had chosen clothes three times too large for me and Hall had chosen some three sizes too small. The distributing sergeant was pretty baffled. We duly signed our names and walked out. England’s heroes were now free men. No more ‘yes, sir, no, sir’, no more parades. Back at the guest house, we have our first meal as civilians. As I remember it was spaghetti.

Milligan and Hall, their first meal as civilians.

∗

We had one more demob appointment. That was with the Army MO. This turns out to be a watery-eyed, red-nosed lout who was to medicine what Giotto was to fruit bottling. “It’s got you down here as B1,” he says.

“That’s right, I was downgraded at a medical board.”

“It says ‘battle fatigue’.”

“Yes. ‘Battle fatigue, anxiety state, chronic’.”

“Yes, but you’re over it now, aren’t you?”

“No, I still feel tired.”

“So, I’ll put you down as A1.”

“Not unless I’m upgraded by a medical board.”

“Oh, all right. Bi.”

He then asks me if my eyesight is all right.

“As far as I know.”

“You can see me, can’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Then it’s all right.”

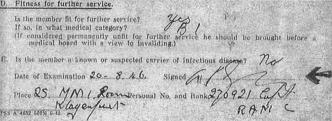

It ended with him signing a couple of sheets of paper and showing me the door. Why didn’t he show me the window? It was a nice view. To give you an idea of the creep, here is his signature.

That was it. I was a civilian and B1.

∗

Ah, Sunday, day of rest and something. On Monday we will travel to Graz and do the show. In the morning I lie abed smoking.

“What’s it feel like to be a civvy?” says Mulgrew.

“Well, I’ve felt myself and it feels fine.”

“Lucky bugger. I’ve still got two months to go,” he said, coughing his lungs up.

“You sound as if you’re going now.”

Bill Hall stirs. “Wot’s the time?”

I tell him, “It’s time you bought a bloody watch.”

Lying in bed, Hall looks like an activated bundle of rags. Poor Bill – he, too, had been to the creep MO, who had passed him out as A1. He didn’t know it at the time but he had tuberculosis, which would one day kill him. So much for bloody Army doctors.

I take a shower and sing through the cascading waters. “Boo boo da de dum, can it be the trees that fill the breeze with rare and magic perfume?” I sing. What a waste, singing in the shower. I should be with Tommy Dorsey or Harry James.

Mid-morning, Hall, Mulgrew and I agree to give a concert in the lounge. It is much enjoyed by the hotel staff. All blue-eyed, blond, yodelling Austrians, who have been starved of jazz during the Hitler regime. They have a request. Can we play ‘Lay That Pistol Down Babe’? Oh, Christ, liberation had reached Austria. To appease them we play it. Hall plays it deliberately out of tune. “I’ll teach the bastards,” he says,

sotto voce con espressione

. They applaud wildly and ask for it again!! Hall can’t believe it. “They must have cloth ears,” he says and launches into ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’ as a foxtrot. “Take your partners for the National Anthem,” he says. Hitler must have turned in his grave.

HITLER:

No, I’m not. I’m still shovelling shit and salt in Siberia.

No sign of Toni so far, then Greta tells me she’s in bed with tummy trouble. I go up to her room. She’s asleep, but awakes as I come in. “What’s the matter, Toni?”

She is perspiring and looks very flushed. “I think I eat something wrong,” she says. “All night I be sick.” Oh dear, can I get her anything on a tray like the head of John the Baptist? “No, I just want sleep,” she says in a tiny voice. So, I leave her.

That afternoon, Lieutenant Priest has arranged a picture show just for us. We all go to the Garrison Cinema in Klagen-furt to see the film

Laura

, with George Sanders and Clifton Webb. It has that wonderful theme song ‘Laura’, after which I would one day name my daughter. We are admitted free under the banner of CSE. The cinema is empty, so we do a lot of barracking.

“Watch it, darling, ‘ees going ter murder yes,” etc. “ee wants to have it away with you, darlin’.”

“Look out, mister, watch yer ring! He’s a poof!” Having destroyed the film, we return home like well-pleased vandals.

Tea is waiting and Toni is up and dressed, she feels a lot better. No, she won’t eat anything except a cup of coffee, so I get her a cup of coffee to eat. I light up my after-dinner fag and pollute the air. Toni flaps her hand. “Oh, Terr-ee, why you smoke?” Doesn’t she know that Humphrey Bogart never appears in a film without smoking? We spend the evening playing ludo with small bets on the side. Suddenly,

I

feel sick. It’s the same as Toni. Soon, I have both ends going. I take to my bed and only drink water. That night, I have a temperature. What a drag! I fall into a feverish sleep.

GRAZ

GRAZ

N

ext morning, I’m still discharging both ends. Wrapped in a blanket, doused with Aspros, I board the Charabong.

“How you feel, Terree,” says Toni.

“Terrible.”

I semi-doze all the way to Graz, showing no interest in food or drink. When we arrive in Graz, I hurriedly book in and make for my room. It’s a lovely hotel with double glazing and double doors to the room, so it’s very quiet except for the noise of me going both ends. I take a hot bath and take to my sick bed. I get visits from everyone. Do I need a doctor? I say, no, a mortician. Will I be doing the show tomorrow? Not bloody likely. Bornheim will have to take my place on the squeeze box; I am delirious. Toni visits me and tells me she loves me. That’s no bloody good. I love her too, but I’ve still got the shits. Can she hurry and leave the room as something explosive is coming on. I fall into a deep sleep. I awake in the wee hours to do a wee. I’m dripping with sweat. What’s the time? 3 a.m. I take a swig at my half-bottle of whisky. When I awake in the morning, I seem to have broken the back of it – it feels as if I’ve also broken its legs and arms. Twenty-four hours had passed away but I hadn’t. In two days I’m back to my normal, healthy, skinny, self. How did the act go with Bornheim deputizing for me? It was great! Curses. So I rejoin the fold.

The show is at the Theatre Hapsburg, a wonderful, small intimate theatre – one mass of gilded carvings of cherubim. This night the trio get rapturous applause from a mixed audience of Austrians and soldiers. Hall is stunned.

“Bloody hell,” he said. “We weren’t

that

good.”

“Rubbish,” says Mulgrew. “‘

They

weren’t good enough!”

Dinner that night was a treat – first food for forty-eight hours. It’s Austrian Irish stew. Bill Hall tells the waitress that his meat is very tough. She calls the chef, a large Kraut. He asks what’s wrong.

“This meat is tough.”

“Oh,” says the Kraut. “You are zer only von complaining.”

“That’s ‘cause I got all the ‘ard bits, mate.”

“It’s zer luck of the draw,” says the Kraut, who takes it away.

The waitress returns with a second portion.

“Yes, this is better,” says Hall. The excitement is unbearable.

I’m convalescing, so I have an early-to-bed. I’m reading Elizabeth GaskelPs

The Life of Charlotte Bronte

. First, I’m delighted to find that the father was Irish. The interesting figure in the story is Branwell Bronte, the piss artist. He’s amazing. He writes reams of poetry, can paint and also write with both hands at once. How’s that for starters. Yet, he is

the failure

of the family. My eyelids are getting heavy. I lay the book aside and sleep peacefully until the morning when there’s a birdlike tapping at my door. It’s morning-fresh Toni. She kisses my eyes. “You very lazee, hurry up. Breakfast nearly finished!” She will see me after breakfast in the hall. “We go for nice walk.” It’s cold but sunny; we are quite high high up.

I have a quick shit, shave and shampoo. I

just

make breakfast. I ask the waiter if I can have a boiled egg and toast. He looks at his watch. Is he going to time it? With an expression on his face as though his balls are being crushed in a vice, he says OK. Toni is waiting in the foyer. She is wearing a tweed coat with a fur collar and looks very pretty. We start our walk by strolling along the banks of the River Mur. Mur? How did it get a name like that? Our walk is lined with silver birch trees. We cross the Mur Bridge and I wonder how it got that name, Mur; through large iron gates into a park built on the side of a hill, called Der Mur Garten, and I wonder how it got that name, Mur. We walk up a slight gradient flanked by rose beds. It was then we did what must be timeless in the calendar of lovers: we carved our names on a tree, inside a heart.

We carved our hearts

On a tree in Graz

And the hands of the clock stood still

Toni has found two heart-shaped leaves, stitched them together with a twig and scratched ‘I love you Terry’ on them. They still lie crumbling in the leaves of my diary. Ah, yesterday! Where did you go? I lean over and pick a rose only to get a shout, “Oi,

nicht gut

!” from a gardener. We climb higher to a lookout platform overlooking the Mur. How

did

it get that name? From here, we walk into the Feble Strasse, the Bond Street of Graz. As we cross the Mur Bridge, each of us tosses a coin into the river. “That mean we come back,” said Toni. We never did. We never will.

We window-gazed. Why are women transfixed by jewellers, handbag and shoe shops? The moment Toni stops at a jeweller’s, I feel that I should buy her a trinket.

“Isn’t that beautiful?” she says, pointing to something like the Crown Jewels, priced thousands of schillings.

“Yes,” I said weakly, knowing that as I stood my entire worldly value, including ragged underwear, was ninety pounds.

The torture doesn’t stop there. She points, “Oh, look, Teree” – a fur coat valued at millions of schillings.

“Yes,” I say weakly, feeling like Scrooge.

“What lovely handbag,” she enthuses.

“Yes,” I say. Don’t weaken, Milligan. As long as you can say yes, you’re safe from bankruptcy. “Look, Toni, isn’t that beautiful?” I say, pointing to a small bar of chocolate for fifty groschen. Mur, how did it get that name? So, nibbling fifty-groschen chocolate, we walk back to the hotel.

During that night’s show, Fulvio Pazzaglia and Tiola Silenzi have a row. Trained singers, their voices projecting can be heard on the stage. She empties a jug of red wine over Fulvio and his nice white jacket. Hurriedly, he borrows one that is miles too big. When he appears on stage, he looks like an amputee. On the way back in the Charabong, the row continues. She does all the shouting, he sits meekly in silence. It’s something to do with money. She spends it and he objects when he can get a word in. We all sit in silence listening to the tirade. It is very entertaining and when she finally finishes, Bill Hall starts up a round of applause, shouting, “Bravo! Encore!” She is beside herself with anger.