Peace Work (20 page)

Authors: Spike Milligan

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Humor & Entertainment, #Humor, #Memoirs

“You see you ladyfriend,” she says in a slightly cool voice.

“Yes, and we’re just good friends.”

“You see her again?”

“No, no.”

This is followed by a silence, then, “You tell me truth.”

Of course, the fact she has a beautiful face, lovely boobs, long shapely legs mean absolutely nothing to me, absolutely nothing!

“What you say to her?”

“Goodbye!”

Toni gives me a long cold stare; I realize what I need is a good solicitor. At dinner, she is friendlier. I tell her, “You are the one I love, you understand?”

Yes, she understands. “But I no like you to see other pretty girl.” I tell her I can’t go around blindfold. She smiles, “All right, but I little

gelosa

, how you say?”

“Jealous.”

“Yes, I jealous.” She eats a few more mouthfuls of food. “But now I all right.”

Good, the heat is off.

“Toni, when the show is finish, you like to come on holiday with me on Capri?”

She is surprised and bemused. “Capri?”

“Yes.”

“Me an’ you on Capri?”

“Yes.”

She’s never done anything like this before. Neither have I. Yes, but we mustn’t tell her mother. That’s fine as long as she doesn’t tell mine!

MOTHER: (Or the landing)

Terry? What time do you call this, where have you been to at this time of night?

ME:

The Isle of Capri, Mum.

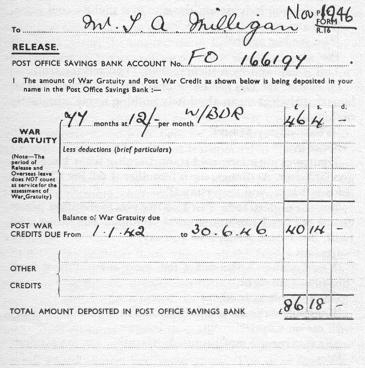

Toni is over the moon at the news. The Isle of Capri! She’s never been there. Where will we stay? Don’t worry, I’ll fix a place. I’m going to cash in my Post-war Credits and my Post Office Savings – a grand total of eighty-six pounds!!! Rich as King Creosote!!!! Eighty-six pounds! Why, that was nearly eighty-seven pounds! Me, who had never had more than ten pounds in my hands. Oh, God, was I really that innocent? Yes, I was; why didn’t I stay that way…

That night I go to bed with my head full of dreams about Capri. I can’t believe that little old me who worked in Woolwich Arsenal dockyard as a semi-skilled fitter, little old me with one fifty-shilling suit, a sports coat and flannels, can afford to go to Capri with an attractive Italian ballerina. Little old me! The furthest I’d been from Brockley was on a school day trip to Hernia Bay on a rainy day! The galling part was I had to thank Adolf Hitler for this dramatic change in my life.

A CONCENTRATION CAMP IN SIBERIA.

HITLER IS SHOVELLING SHIT AND SALT.

HITLER:

You see? You fools? If you had kept me on zen EVERYONE would be going to Capri, nein?

Johnny Mulgrew and Johnny Bornheim come into the room. They’ve been drinking at the vino bar next door and are very merry. “Ah, look at the little darling, in bed already,” says Mulgrew. Bornheim has a bottle of red wine which he holds up in front of me with a grin. What the hell! OK, I’ll have a glass. The three of us sit drinking and yarning. All of us are yearning for our tomorrows to mature; we are all suspended in an exciting but unreal life. We realize that this is a post-war world with people still mourning the death of sons and husbands, and we are a band of Merry Andrews with absolutely nothing to worry about. We drink again and again, and get more and more morose.

“I’m going to bed,” lisps Bornheim, “before I start to cry.”

Mulgrew takes off trousers and shirt and in a short vest that

just

covers his wedding tackle, climbs into the pit and, before I am, he is asleep with a long snore in the key of G.

How do I know? Like my mother I have perfect pitch. Back home, if I dropped a fork on the floor with a clang, my mother would say what key it was in. Apparently, if I remember rightly, I was eating my breakfast in E flat. I drift off into sleep as Mulgrew changes key.

∗

“Ah,” says Mulgrew to the morning, “it’s a beautiful day.”

“It’s raining,” I say.

“Ah, yes, but today,” he pauses and sings in a false opera voice. “it’s Payyyyyyyyyy dayyyyyyyyyy.”

I sing back, “Sooooooo it issssss and if I remember you owe me one thousand lireeeeeeeeeeee.”

“Ohhhhhhhhhhh, buggerrrrrrrrrrrr.” Mulgrew disappears into the WC. His voice comes wafting, “What’s all this paper on the seat?” I tell him it’s against deadly diseases. I’m sorry I forgot to flush it away – how embarrassing! “What do you think you’re going to catch?” he says, straining to his task.

“Leprosy, Shankers and the Clap.”

“The Holy Trinity of Scotland,” he says still straining.

I leap from my bed in my blue pyjamas in which all the dye has run. I take a hot shower, singing all the while: “When I sing my serenade, our big love scene will be played, boo boo da de da de dum.” I watch the water cascade down my body making it shine as though I had been varnished. I quickly turn the shower to cold, giving off screams of shock.

“Have you caught something?” strains Mulgrew.

“Yes. Pneumonia,” I scream and sing ‘Pneumonia a Bird in a Gilded Cage’.

It’s a good morning, we feel good. Mulgrew has his shit, shave and shampoo and we toddle down for breakfast. We meet Toni and Luciana on the stairs. “

Buon giorno, mio tesoro

,” I say to her. Today would we like to go to the Vatican? What a splendid idea. Who knows, we might see the Pope. “Hello Pope,” I’ll say, “I’m a Catholic, too! Can I have a piece of the True Cross for my mother? And can you bless my Bing Crosby voice?” First, I visit our Lieutenant to draw my ten pounds wage which came to twelve thousand lire – twelve

thousand

, it sounded so rich. Well set up, I meet Toni and we hail a taxi.

“Hail Taxi,” I call, doing the Hitler salute.

“Wot you do, Terr-ee?” says Toni, laughing.

“La Vaticino,” I tell the driver. My God, I’m speaking the lingo well.

Sitting back and holding hands, I can’t resist a tender morning kiss. Oh, sentimental old me! Toni’s lips are soft and velvety; mine are ever so slightly chapped, but she doesn’t complain. It shows you what can be obtained with second-hand equipment. Where are we? We’re on the Corso Vittorio Emanuele and about to cross the River Tiber. On the right riverbank is the great Castle San Angelo. On, to the Via Conciliazione which runs directly into the great St Peter’s Square with its great semi-circular colonnade by Bernini. The whole place is teeming with visitors and numerous vendors of holy relics, pictures of Pope Pius, rosaries, etc. The taxi sets us down, and we walk up to the Sistine Chapel with the Swiss Guards outside in their blue and yellow uniforms designed by Michelangelo.

Now, dear reader, to try and describe the treasures on view would fill six volumes. I’m not going to put you to that expense – no, suffice it to say that there were so many masterpieces they made you giddy. I was moved by one particular piece: that was th’e Pieta by Michelangelo. It was like a song in stone. Toni and I wander round the great Basilica of St Peter’s, totally overawed. All I can think of is that God is very, very rich. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a concentration of creative art. Toni keeps saying, “

Che fantastico

, Terr-ee.”

The morning passes and by lunchtime we’ve had enough. Outside, I decide to buy a rosary in a small container embossed with the image of Pope Pius. My mother will love it as it has apparently been blessed by the Pope. “

Benedetto dallo papa

,” says the lying vendor. What shall we do now, Toni? She would like to sit down. We walk back across the great square and just outside find a small coffee house where we order two small coffees. We sit outside. Tides of the faithful are going back and forth to the Vatican with a mixture of nuns and clerics in black hats and schoolchildren buzzing with excitement – it’s THE VATICAN SHOW! Toni laments that we haven’t seen the Pope.

“

Mi displace

,” she says, pulling a wry face.

Don’t worry, dear, he didn’t see us either and when you’ve seen one pope you’ve seen ‘em all.

We discuss what to do when the show finally finishes on Saturday. Toni will, of course, stay at home; her mother can’t understand why her daughter stays at a hotel when her home is in Rome. What will I do? Can I stay on? No, I have a better idea. We go back with the company, go to the Isle of Capri, spend a week there, then come back to Rome and stay until my ship sails. She agrees. There are a few problems, like how do I get my wages when I come back to Rome, but I’ll try and fix that with the CSE cashier – that, or a bank robbery should suffice. I can always sell the rosary. I light up an after-tea cigarette. “What it taste like?” says Toni. “I like to try.” She takes a puff, starts coughing with eyes watering. “How can you smoke like that thing?

Sono Urribili

” she splutters. Serves her right; cigarettes are man’s work.

It’s a very hot day and we decide to go back to the hotel. Again, we take a taxi. It’s but a twenty-minute journey to the hotel. Once there, Toni wants to wash her hair. I retire to my bed and read Mrs Gaskell’s book on the Brontes. What a family! All the children literally burn with creative talent. Oh, for just a day in their company. I have a siesta (that means sleeping in Italian) until tea-time when I am awakened by Scotland’s gift to the world, Johnny Mulgrew, bass player extraordinary to the House of Johnnie Walker. He’s been to the pictures: “Saw a bloody awful film.” Oh? You interest me Mulgrew, what was this bloody awful film? Betty Grable and her legs in

The Dolly Sisters

. “The dialogue was an insult to the intelligence,” he said, flopping on his bed. Insult to the intelligence, eh? I didn’t know he’d taken that with him. Never, never take your intelligence to a Betty Grable movie. It’s best viewed from the waist down. Had he been paid yet? Yes.

“Two thousand lire, please,” I said.

That hurts him, his Scottish soul is on the rack. He pulls the amount from his padlocked wallet and, with a look of anguish, hands me the money.

I buzz room service and order tea for myself and my Scottish banking friend. A blue-chinned waiter with a slight stoop brings it in. I give him a tip.

“How much you tip him?” says Mulgrew.

“Ten lire.”

Mulgrew groans. “What a waste. That’s five cigarettes.”

I pour him a tea and drink my Russian one.

“What’s that taste like?” he says.

I tell him I never knew the real taste of tea until Toni got me on to lemon tea. Would he like a sip? No, he wouldn’t. I like a man who knows his own mind.

I take some of my clothes to the washing lady and ask her to ‘

stirare

’ (iron) them. She’ll have them by tomorrow morning. She’s a big, fat, voluble Italian lady who, you feel, would do anything for anybody. She smiles and nods her head – such dexterity! Coming up the stairs with his suit is one of our chorus boys, Teddy Grant. “Ah, ha! Teddy, how’s the romance with Greta Weingarten?” It’s platonic; they’re just good friends. As Teddy is gay, that makes sense – not much though. To me, it’s an enigma.

Back in the room, I have a little practice on my guitar, trying to remember Eddy Lang’s* solo ‘April Kisses’.

≡ Popular jazz guitarist of the twenties and thirties.

Mulgrew listens, then says it’s one of the most mediocre renderings he’s ever heard. I keep practising. At the end of an hour he says, “It’s the most mediocre rendering I’ve ever heard.” Never mind, I had it over him –

he

couldn’t tell what key forks were in when they hit the ground.

∗

The show that night is held up; the electric front curtain has fused. The stagehands try the manual lift, but that doesn’t work either. However, suddenly, when the electrician is tinkering with the mechanism, it shoots up revealing the set and several stagehands who run off as though being seen on a stage meant instant death. Otherwise, the show runs as per usual. In the dressing-room, the three of us discuss when we should be getting together in the UK to start our fabulous stage career. I tell them I won’t be home until late October; Johnny isn’t discharged until December, so we decide to start afresh in the New Year.

Jimmy Molloy comes round with a book of raffle tickets. It’s for two bottles of scotch, ten lire a ticket. I take ten, Johnny takes one, Bill doesn’t drink whisky – he’s not interested. The draw is after the show in Molloy’s dressing-room. At the appointed hour we all cram into his room. Luciana draws the tickets from a top hat. Mulgrew, with one measly ticket, wins! He is very generous. That night, after dinner, we gather in the lounge and he gives us all a measure – the toast is ‘Scotland for ever’!! Toni wants to try some; she sips mine, has a coughing fit with watering eyes. Serves her right! Whisky is man’s work.

It’s my lucky night: Luciana is staying with her parents, so Toni is alone. We spend a lovely night together and the devil take the hindmost. Awake, for morning in a bowl of light has put the stars to flight! So I awake, with Toni still sleeping soundly. I dress quickly so she doesn’t have to see my skinny body at such close range. Don’t willies look silly in the morning light? I tippy-toe out, seeing no one sees me, and make my way back to my room.