Pediatric Primary Care (121 page)

a. RBC hypochromic, microcytic.

b. Mean cell volume (MCV) decreased.

c. Ratio of MCV/RBC > 13 (Mentzer index).

• > 13 = iron-deficiency anemia.

• < 13 = thalassemia trait.

3. Iron studies if need further information.

a. Serum iron: decreased.

b. Total iron-binding capacity: increased.

c. Ferritin: decreased.

d. Percentage of iron saturation: decreased.

G. Differential diagnosis.

| Lead poisoning, 984.9 |

| Sideroblastic anemia, 285 |

| Thalassemia, 282.49 |

1. Thalassemia trait.

2. Lead poisoning.

3. Chronic infection.

4. Sideroblastic anemia.

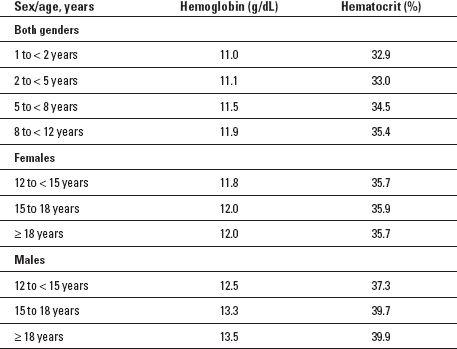

Table 32-1

Maximum Hemoglobin Concentration and Hematocrit Values for Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Source

: Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1998, April 3). Recommendations to prevent and control iron defi ciency in the United States.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

, 47(RR-3), 1-36.

H. Treatment.

1. Nutritional strategies.

2. Reduce milk to no more than 16-24 oz/day.

a. Increase intake of high-iron foods (e.g., beans, whole cereals, dried fruit, pork, beef).

b. Iron therapy for infants and children:

• Ferrous sulfate.

i. Mild to moderate iron deficiency: elemental iron 3 mg/kg/day in 1-2 divided doses.

ii. Severe iron deficiency: elemental iron 4-6 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses.

I. Follow up.

1. Recheck hemoglobin in 1 month.

2. Treat until hemoglobin and hematocrit reach normal ranges. Then give at least 1 month additional treatment to replenish iron stores.

3. If response not adequate within 1-2 months, consider further diagnostic testing for GI bleeding or other microcytic hypochromic anemias.

J. Complications.

| | |

| Anemia, 280.9 | Developmental delays, 783.4 |

| Behavioral delays, 312.9 | Poor growth, 253.2 |

| |

1. Result from long-standing iron-deficiency anemia.

a. Increased susceptibility to infection.

b. Poor growth.

c. Developmental delays (lower mental and motor test scores).

d. Behavioral delays.

K. Education.

1. Need for balanced diets and foods containing iron.

a. Cereal, egg yolks, green/yellow vegetables, yellow fruits, red meat, potatoes, tomatoes, raisins.

2. Amount of milk necessary/day (age dependent).

3. Information about iron medications:

a. Give after meals with orange juice to enhance absorption.

b. Do not give with milk (inhibits absorption of iron).

c. Give with straw or brush teeth after giving (may stain teeth).

d. May cause abdominal discomfort, constipation, black stools.

e. Extremely poisonous if taken in excessive amounts.

f. Keep out of reach of small children.

II. THALASSEMIA

A. An inherited anemia that can affect both males and females and can be mild or severe. Hemoglobin has two types of protein chains, alpha globin and beta globin, which are needed to properly form the red blood cell and allow it to then carry enough oxygen. Therefore one can have either an alpha thalassemia or a beta thalassemia. It occurs most often in people of Italian, Greek, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African descent. Severe form is usually diagnosed in early childhood and is a lifelong condition.

B. Etiology.

1. Alpha thalassemia: need 4 genes (2 from each parent) to make enough alpha protein chains, located on chromosome 16.

a. Mild anemia.

• One missing gene, silent carrier, no symptoms.

• Two missing genes—carrier and mild anemia.

b. Moderate to severe anemia.

• Three missing genes—hemoglobin H disease.

• Four missing genes—alpha thalassemia major or hydrops fetalis.

2. Beta thalassemia—need 2 genes (one from each parent) to make enough beta globin protein—located on chromosome 11.

a. Mild anemia.

• One missing or altered gene—carrier status.

b. Moderate or severe anemia.

• Two missing or altered genes.

i. Beta thalassemia intermedia—moderate anemia.

ii. Beta thalassemia major—Cooley's anemia, severe.

C. Occurrence.

1. Family history and ancestry are the two risk factors.

a. Alpha thalassemias most often affect ancestry origin of Indian, Chinese, Filipino, or Southeast Asian.

b. Beta thalassemias most often affect ancestry origin of Mediterranean (Greek, Italian, Middle Eastern), Asian, or African.

D. Clinical manifestations.

1. No symptoms if a silent carrier as in alpha thalassemia.

2. May or may not have symptoms with mild anemia—usually fatigue—most often mistaken for IDA.

3. More severe symptoms with moderate anemia that may include slowed growth and development and physical problems with bones and the spleen.

4. Symptoms of severe anemia due to thalassemias occur during the first 2 years of life and include other serious health problems besides the severe anemia.

E. Physical findings.

1. Mild anemia—normal physical exam.

2. More severe anemia.

a. Pale and listless appearance.

b. Poor appetite.

c. Dark urine.

d. Jaundice.

e. Enlarged spleen, liver, and heart.

f. Bone problems, especially the bones of the face.

g. Delayed puberty.

h. Slowed growth.

F. Diagnostic tests.

1. CBC with differential.

2. Iron tests—to rule out IDA.

3. Hemoglobin tests.

4. Genetic studies.

G. Differential diagnosis.

1. IDA.

2. Other anemias.

H. Treatment.

1. Mild forms need no treatment.

2. Moderate to severe forms.

a. Regular blood transfusions—RBCs live 120 days so may need transfusions for severe anemia every 2 to 4 weeks.

Other books

Demon Blood (Vampire in the City Book 5) by Donna Ansari

The Radiant Dragon by Elaine Cunningham

Alena: A Novel by Pastan, Rachel

Prince Charming in Dress Blues by Maureen Child

Love Required by Melanie Codina

A Fighting Chance by Annalisa Nicole

Songs Only You Know by Sean Madigan Hoen

One of Us by Jeannie Waudby

The Vinyl Princess by Yvonne Prinz

Of Loss & Betrayal (Madison & Logan Book 2) by S.H. Kolee