Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind (31 page)

Read Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind Online

Authors: V. S. Ramachandran,Sandra Blakeslee

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

involved? Even more puzzling, why do they take this particular form? Why don't these patients hallucinate pigs or donkeys?

124

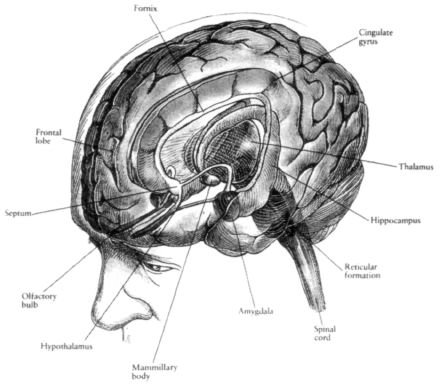

In 1935, the anatomist James Papez noticed that patients who died of rabies often experienced fits of extreme rage and terror in the hours before death. He knew that the disease was transmitted by dog bites and reasoned that something in the dog's saliva—the rabies virus—traveled along the victim's peripheral nerves located next to the bite, up the spinal cord and into the brain. Upon dissecting victims' brains, Papez found the destination of the virus—clusters of nerve cells or nuclei connected by large C−shaped fiber tracts deep in the brain (Figure 9.1). A century earlier, the famous French neurologist Pierre Paul Broca had named this structure the limbic system. Because rabies patients suffered violent emotional fits, Papez reasoned that these limbic structures must be intimately involved in human emotional behavior.2

The limbic system gets its input from all sensory systems—vision, touch, hearing, taste and smell. The latter sense is in fact directly wired to the limbic system, going straight to the amygdala (an almond−shaped structure that serves as a gateway into the limbic system). This is hardly surprising given that in lower mammals, smell is intimately linked with emotion, territorial behavior, aggression and sexuality.

The limbic system's output, as Papez realized, is geared mainly toward the experience and expression of emotions. The experience of emotions is mediated by back−and−forth connections with the frontal lobes, and much of the richness of your inner emotional life probably depends on these interactions. The outward expression of these emotions, on the other hand, requires the participation of a small cluster of densely packed cells called the hypothalamus, a control center with three major outputs of its own. First, hypothalamic nuclei send hormonal and neural signals to the pituitary gland, which is often described as the "conductor" of the endocrine orchestra. Hormones released through this system influence almost every part of the human body, a biological tour de force we shall consider in the analysis of mind−body interactions (Chapter 11). Second, the hypothalamus sends commands to the autonomic nervous system, which controls various vegetative or bodily functions, including the production of tears, saliva and sweat and the control of blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, respiration, bladder function, defecation and so on. The hypothalamus can be regarded, then, as the "brain" of this archaic, ancillary nervous system. The third output drives Figure 9.1

Another view of the limbic system. The limbic system is made up of a series of interconnected

structures surrounding a central fluid−filled ventricle of the forebrain and forming an inner border of the

125

cerebral cortex. The structures include the hippocampus, amygdala, septum, anterior thalamic nuclei,

mammillary bodies and cingulate cortex. The fornix is a long fiber bundle joining the hippocampus to the

mammillary bodies. Pictured also are the corpus callosum, a fiber tract joining right and left neocortex, the

cerebellum, a structure involved in modulating movement, and the brain stem. The limbic system is neither

directly sensory nor motor but constitutes a central core processing system of the brain that deals with

information derived from events, memories of events and emotional associations to these events. This

processing is essential if experience is to guide future behavior (Winsen, 1985).

Reprinted from

Brain, Mind

and Behavior

by Bloom and Laserson (1988) by Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Used with permission from W. H. Freeman and Company.

actual behaviors, often remembered by the mnemonic the "four F's"— fighting, fleeing, feeding and sexual behavior. In short, the hypothalamus is the body's "survival center," preparing the body for dire emergencies or, sometimes, for the passing on of its genes.

Much of our knowledge about the functions of the limbic system comes from patients who have epileptic seizures originating in this part of the brain. When you hear the word "epilepsy," you usually think of someone having fits or a seizure—the powerful involuntary contraction of all muscles of the body—and falling to the ground. Indeed, these symptoms characterize the most well−known form of epilepsy, called a grand mal seizure. Such seizures usually arise because a tiny cluster of neurons somewhere in the brain is misbehaving, firing chaotically until activity spreads like wildfire to engulf the entire brain. But seizures can also be "focal"; that is, they can remain confined largely to a single small patch of the brain. If such focal seizures are mainly in the motor cortex, the result is a sequential march of muscle twitching—or the so−called jacksonian seizures. But if they happen to be in the limbic system, then the most striking symptoms are emotional. Patients say that their "feelings are on fire," ranging from intense ecstasy to profound despair, a sense of impending doom or even fits of extreme rage and terror. Women sometimes experience orgasms during seizures, although for some obscure reason men never do. But most remarkable of all are those patients who have deeply moving spiritual experiences, including a feeling of divine presence and the sense that they are in direct communion with God. Everything around them is imbued with cosmic significance. They may say, "I finally understand what it's all about. This is the moment I've been waiting for all my life. Suddenly it all makes sense." Or, "Finally I have insight into the true nature of the cosmos." I find it ironic that this sense of enlightenment, this absolute conviction that Truth is revealed at last, should derive from limbic structures concerned with emotions rather than from the thinking, rational parts of the brain that take so much pride in their ability to discern truth and falsehood.

God has vouchsafed for us "normal" people only occasional glimpses of a deeper truth (for me they can occur when listening to some especially moving passage of music or when I look at Jupiter's moon through a telescope), but these patients enjoy the unique privilege of gazing directly into God's eyes every time they have a seizure. Who is to say whether such experiences are "genuine" (whatever that might mean) or

"pathological"? Would you, the physician, really want to medicate such a patient and deny visitation rights to the Almighty?

The seizures—and visitations—last usually only for a few seconds each time. But these brief temporal lobe storms can sometimes permanently alter the patient's personality so that even between seizures he is different from other people.3 No one knows why this happens, but it's as though the repeated electrical bursts inside the patient's brain (the frequent passage of massive volleys of nerve impulses within the limbic system) permanently "facilitate" certain pathways or may even open new channels, much as water from a storm might pour downhill, opening new rivulets, furrows and passages along the hillside. This process, called kindling, might permanendy alter—and sometimes enrich—the patient's inner emotional life.

126

These changes give rise to what some neurologists have called "temporal lobe personality." Patients have heightened emotions and see cosmic significance in trivial events. It is claimed that they tend to be humorless, full of self−importance, and to maintain elaborate diaries that record quotidian events in elaborate detail—a trait called hypergraphia. Patients have on occasion given me hundreds of pages of written text filled with mystical symbols and notations. Some of these patients are sticky in conversation, argumentative, pedantic and egocentric (although less so than many of my scientific colleagues), and they are obsessively preoccupied with philosophical and theological issues.

Every medical student is taught that he shouldn't ever expect to see a "textbook case" in the wards, for these are merely composites concocted by the authors of medical tomes. But when Paul, the thirty−two−year−old assistant manager of a local Goodwill store, walked into our lab not long ago, I felt that he had strolled straight out of

Brain's Textbook of Neurology

—the Bible of all practicing neurologists. Dressed in a green Nehru shirt and white duck trousers, he held himself in a regal posture and wore a magnificent jeweled cross at his neck.

There is a soft armchair in our laboratory, but Paul seemed unwilling to relax. Many patients I interview are initially uneasy, but Paul was not nervous in that sense—rather, he seemed to see himself as an expert witness called to offer testimony about himself and his relationship with God. He was intense and self−absorbed and had the arrogance of a believer but none of the humility of the deeply religious. With very little prompting, he launched into his tale.

"I had my first seizure when I was eight years old," he began. "I remember seeing a bright light before I fell on the ground and wondering where it came from." A few years later, he had several additional seizures that transformed his whole life. "Suddenly, it was all crystal clear to me, doctor," he continued. "There was no longer any doubt anymore." He experienced a rapture beside which everything else paled. In the rapture was a clarity, an apprehension of the divine—no categories,

no boundaries, just a Oneness with the Creator. All of this he recounted in elaborate detail and with great persistence, apparently determined to leave nothing out.

Intrigued by all this, I asked him to continue. "Can you be a little more specific?"

"Well, it's not easy, doctor. It's like trying to explain the rapture of sex to a child who has not yet reached puberty. Does that make any sense to you?"

I nodded. "What do you think of the rapture of sex?"

"Well, to be honest," he said, "I'm not interested in it anymore. It doesn't mean much to me. It pales completely beside the divine light that I have seen." But later that afternoon, Paul flirted shamelessly with two of my female graduate students and tried to get their home telephone numbers. This paradoxical combination of loss of libido and a preoccupation with sexual rituals is not unusual in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

The next day Paul returned to my office carrying an enormous manuscript bound in an ornate green dust jacket—a project he had been working on for several months. It set out his views on philosophy, mysticism and religion; the nature of the trinity; the iconography of the Star of David; elaborate drawings depicting spiritual themes, strange mystical symbols and maps. I was fascinated, but baffled. This was not the kind of material I usually referee.

When I finally looked up, there was a strange light in Paul's eyes. He clasped his hands and stroked his chin with his index fingers. "There's one other thing I should mention," he said. "I have these amazing flashbacks."

127

"What kind of flashbacks?"

"Well, the other day, during a seizure, I could remember every little detail from a book I read many years ago.

Line after line, page after page word for word."

"Are you sure of this? Did you get the book and compare your memories with the original?"

"No, I lost the book. But this sort of thing happens to me a lot. It's not just that one book."

I was fascinated by Paul's claim. It corroborated similar assertions I had heard many times before from other patients and physicians. One of these days I plan to conduct an "objective test" of Paul's astonishing mnemonic abilities. Does he simply imagine he's reliving every minute detail? Or, when he has a seizure, does he lack the censoring or editing

that occurs in normal memory so that he is forced to record every trivial detail—resulting in a paradoxical improvement in his memory? The only way to be sure would be to retrieve the original book or passage that he was talking about and test him on it. The results could offer important insights about how memory traces are formed in the brain.

Once, when Paul was reminiscing about his flashbacks, I interjected, "Paul, do you believe in God?"

He looked puzzled. "But what else

is

there?" he said.

But why do patients like Paul have religious experiences? I can think of four possibilities. One is that God really does visit these people. If that is true, so be it. Who are we to question God's infinite wisdom?

Unfortunately, this can be neither proved nor ruled out on empirical grounds.

The second possibility is that because these patients experience all sorts of odd, inexplicable emotions, as if a cauldron had boiled over, perhaps their only recourse is to seek ablution in the calm waters of religious tranquility. Or the emotional hodgepodge may be misinterpreted as mystical messages from another world.

I find the latter explanation unlikely for two reasons. First, there are other neurological and psychiatric disorders such as frontal lobe syndrome, schizophrenia, manic depressive illness or just depression in which the emotions are disturbed, but one rarely sees religious preoccupations in such patients to the same degree.

Even though schizophrenics may occasionally talk about God, the feelings are usually fleeting; they don't have the same intense fervor or the obsessive and stereotyped quality that one sees in temporal lobe epileptics.