Pirates of Somalia (13 page)

Read Pirates of Somalia Online

Authors: Jay Bahadur

Tags: #Travel, #Africa, #North, #History, #Military, #Naval, #Political Science, #Security (National & International)

* * *

Our meeting over, Garaad got up and silently walked away. An hour after he left, a call came to Warsame’s phone: it was Garaad, asking for his help to arrange an interview with President Farole. As with Boyah, his reason for talking to me had been rendered perfectly transparent.

He was, I heard, already back with his friends, chewing khat as the sun set.

6

Flower of Paradise

T

HE ARRIVAL OF KHAT IN

G

AROWE IS A CURIOUS SIGHT

.

Each day at around noon, the first khat transports begin to roll in from Galkayo, coinciding with the typical waking hour for a pirate. The angry honking of the incoming vehicles rouses the city from its lethargy, bringing expectant crowds flocking into the streets in defiance of the midday heat. Screaming down the highway at reckless speeds, high beams flashing, guards perched on top, the transports arrive on the southern road. Turning off the highway and rumbling down the embankment towards Garowe’s main checkpoint, they are eagerly greeted by barking soldiers, who fill their arms with leafy bundles before waving the vehicles through. Behind the barrier, a fleet of white station wagons stands ready to be loaded; hired hands follow behind female merchants decked in vibrant headdresses, hauling rectangular bushels wrapped in brown canvas.

As the transports arrive at the khat market, or

suq

, the whole city begins to buzz with activity. Throngs of shouting men press into the

suq

as older children and adolescents mob the transports, hoping to snatch what they can in the scramble of the unloading. In the poorer neighbourhoods, barefoot children gather in circles in front of hovels, slapping hands and jostling for a few stalks scattered in the dust. Even the goats respond with Pavlovian consistency to the tooting of the station wagons, trotting after them in the hopes of nabbing a few fallen leaves.

This is the most significant daily event in Garowe life, repeated with unfailing precision every single day of the year. Steadily increasing in popularity in recent years, khat has become—along with livestock and fishing—one of Puntland’s most lucrative economic sectors. As a Puntland cabinet minister once told me: “In Somalia, there are two industries that work:

hawala

[money transfer] and khat.” If so, piracy has certainly made the khat trade work even better—since late 2008, the

suq

has been awash with the freshly minted bills of pirate ransoms, threatening to turn a tolerable vice into a national addiction.

* * *

Across clime, culture, and continent, people will find some way to intoxicate themselves. In Somalia, a uniformly Islamic society where alcohol consumption is highly taboo, the intoxicant of choice is khat, an amphetamine-like stimulant consumed either by chewing the plant’s leaves or by steeping its dried leaves to make a tea.

Khat—which the Arabs nicknamed the “flower of paradise”—has for centuries been used by Muslim scholars to assist the performance of their intensive day- and night-long studies (and, in more modern times, by Kenyan and Ethiopian students cramming for exams).

1

Growing up to twenty metres high, the plant is extremely water-intensive and better suited to altitudes of 1,500–2,500 metres, giving the Ethiopian highlands and the provinces of northern Kenya a strong natural advantage over Somalia. Once confined to East Africa, the demand for the drug has been globalized over the last twenty years by refugees from conflicts in Somalia and Ethiopia; facilitated by modern transportation technologies, khat can now readily be found on the streets of London, Amsterdam, Toronto, Chicago, and Sydney.

2

A social drug, khat is usually chewed for hours on end by groups of friends in picnic-like settings. Owing to its bitter taste, it is often accompanied by a special, heavily sugared tea or other sweet beverage, such as 7-Up. Once harvested, the plant retains its potency for only a short time and must be consumed fresh—the plant’s active chemical, cathinone, breaks down within forty-eight hours after its leaves have dried—a fact that explains its previous lack of international distribution. Shipments to Puntland are flown three times daily from Nairobi and Addis Ababa into Galkayo airport. As is often the case with products designated for export, the khat that finds its way into Garowe is reputed to be of the lowest quality.

One company, SOMEHT, is responsible for importing virtually all of Puntland’s khat, around seven thousand kilograms per day as of 2006.

3

According to Fadumo—a Garowe khat merchant whom I interviewed—each plane is greeted at the airstrip by large numbers of independent distributors, who deploy a network of transports for the slow and bumpy 250-kilometre journey from Galkayo to Garowe. Such is the addiction inspired by this delectable plant that crowds of youth throw up improvised roadblocks composed of small rocks or metal drums at frequent intervals by the sides of the road. At these unofficial checkpoints the young men, often armed with Kalashnikovs, clamour for handouts of the shrub. The drivers are happy to mollify their dangerous fans, throwing offerings of khat out the window at the outstretched hands as they pass. On rare occasions, these self-appointed tax collectors become too persistent, and are shot at, and sometimes killed, by the security guards stationed atop the trucks. Nonetheless, the khat trade generates relatively little attendant violence; Fadumo had never heard of a shipment being hijacked.

4

Once the transports arrive at the main checkpoint outside Garowe, individual merchants meet them and transfer the cargo to their own cars. Fadumo’s arrangements were informal; she tended to buy from a regular distributor, but would sometimes go to other suppliers for smaller amounts, or if her supplier was out of stock.

Though khat has long been a facet of Somali life, the last decade has seen imports into the country soar, and Puntland’s piracy explosion in late 2008 brought consumption levels onto a whole new plane. Outside of cars and khat, there is not much available in Puntland on which to spend tens of thousands of dollars, and pirates are famous for the almost religious fervour with which they chew the drug (though they seem to lack the corresponding devotion to Koranic study). So overblown is the pirates’ infatuation with khat that at times it approaches comical proportions; there are stories, from the early days of multimillion-dollar ransoms, of recently paid pirates rushing to the khat

suq

and spending their US hundred-dollar bills as if they were thousand-shilling notes (which are worth about three cents).

Even without this absurd level of reckless spending, the money disappears remarkably quickly. A successful pirate is expected to share his good fortune with his friends and relatives; the moment he steps off the ship, his money begins to diffuse through an endless kinship network, ending only when the last of the khat leaves have been chewed up and spit out.

* * *

In its short-term effects, khat resembles its South American equivalent, the coca leaf, causing mild euphoria, heightened energy, garrulousness, and appetite loss. Another effect is the belief in one’s own invincibility, which many Somalis view as a factor contributing to the endemic conflict plaguing their country; like pirates, Somali militants are renowned for their rampant khat use, and the drug is thought to help fuel the violence (albeit to a lesser degree than in Liberia, where warlords reputedly rubbed cocaine into the open wounds of their soldiers before sending them into battle).

5

As Jamal, my neighbour during the last leg of my flight into Somalia, eloquently explained, “When people chew khat they believe that they have superhuman strength. They would even think they could lift this plane,” raising his arms above his head in a hoisting motion.

Despite such inestimable benefits, the deleterious health effects of khat are both abundant and unpalatable. Short-term withdrawal symptoms include depression, irritability, nightmares, constipation, and tremors, while long-term use of the drug can lead to ulcers, decreased liver function, tooth decay, and possibly some forms of mental illness. The physical ills of the drug are compounded by its social ones; the UN World Food Programme, for example, has reported that in some areas of Puntland the high costs associated with khat consumption are the main reason for not sending children to school (primary school fees are about eight dollars per month) as well as for high divorce rates.

6

There are also some not-so-scientifically-documented effects. My Somali host, Abdirizak, claimed that khat causes sperm to leak into men’s urine—eventually rendering them infertile—which he humorously cited as the principal reason that frustrated wives try at all costs to keep their husbands away from it. Like many folk-medicine theories, Abdi’s may have had a basis in truth; there is some evidence that long-term khat abuse can lead to a diminished sex drive. In the short term, conversely, it can have quite the opposite effect.

“When some men chew khat, they need to have a woman immediately,” Abdi once explained to me. “They can’t control themselves.” Indeed, those who prepped me for my own khat experience agreed that the drug would bring about one of two scenarios: I would either become relaxed and talkative, or a sex-crazy maniac bent on immediate satiation. But after all the buildup, I didn’t feel much of anything. Four hours of chewing the bitter filth made me sweaty, jittery, sick to my stomach, and, finally, mildly contented. It did not strike me as an equitable trade-off, yet those who can afford it spend their days chewing khat leaves like a cow on her cud.

In the end, I chewed khat six or seven times during my visits to Puntland, out of perverse pragmatism. In spite of a lifetime of exposure to anti-drug public service ads, I continued chewing simply to fit in. More accurately, I discovered that khat was an incredible interviewing tool; it rendered my interviewees relaxed and talkative, with a compelling urge to express themselves. Interviews could go on for hours so long as the khat continued to flow.

* * *

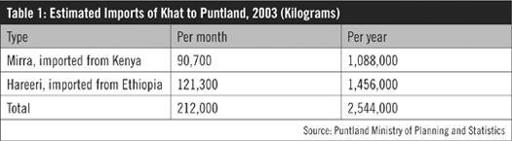

There are few comprehensive academic studies of the Somali khat trade, and any attempt to obtain accurate information on the khat economy suffers from the general dearth of official statistics about Somalia. The latest government figures come from a 2003 report by the Puntland Ministry of Planning and Statistics, which devotes less than one of its sixty pages to the topic. Concluding with the vague assertion that “khat trade and consumption play an adverse role in the Somali economy in general and particularly in Puntland,” the report nonetheless provides some concrete figures (see

Table 1

).

7

These statistics are enough to construct a rudimentary sketch of the Puntland khat industry of eight years ago. Urban street prices for khat, according to my sources, have remained fairly steady at twenty dollars per kilogram over the last decade (in remote areas the price can be almost double), suggesting that total revenues in 2003 fell just short of $51 million. Using the UN Development Programme’s 2006 Puntland population estimate of 1.3 million, the per capita consumption rate would be around 2.1 kilograms per person. However, khat consumers in Puntland are almost without exception men, and after narrowing the field to males aged fifteen and over,

8

annual per capita consumption climbs to 9.1 kilograms, worth about $180. Other sources support this estimate; for example, a 2001 study by the UN’s Water and Sanitation Programme found that poor consumers (the vast majority of Puntlanders) spent an average of $176 per year on the drug.

These numbers, however, are from the pre-piracy era. How might they look in 2011? Attempting to gauge piracy’s effect on khat sales in Puntland, I spoke to three Garowe-based merchants. The first was the aforementioned Fadumo, a bored-looking middle-aged woman with stylish beige sunglasses pushed up on the headdress of her fuchsia

guntiino

(a garment similar to a sari). My second conversation was with a pair of close friends in their late twenties, Maryan and Faiza, who owned side-by-side stalls in the khat

suq

. (I later discovered that Maryan—probably the most stunning Somali woman I had ever seen—was a member of Garaad’s rumoured harem of wives, a fact she admitted with an embarrassed giggle, asking how I had learned of it.)

9

Fadumo worked long hours, from ten in the morning until ten at night. Her most profitable period was from one to three in the afternoon, when government employees got off work; four o’clock, the time that construction workers finished their day, heralded another mini rush hour. Her best days came at the end of the month, when soldiers were paid, and the two or three times per year that Puntland’s parliament was in session. “When there’s an election, that’s the very best time,” she said, because each candidate would arrive with a large entourage in tow, filling Garowe’s hotels to capacity.