Poisoned Bride and Other Judge Dee Mysteries (3 page)

Read Poisoned Bride and Other Judge Dee Mysteries Online

Authors: Robert H. van Gulik

The tribunal, which plays such a prominent role in every Chinese detective story, is a part of the offices of the district magistrate, the town hall, as we would call it. These offices consist of a large number of one-storied buildings, separated from each other by courtyards and galleries. This compound is surrounded by a high wall. On entering through the main gate, an ornamental archway flanked by the quarters of the guards, one finds the court hall at the back of the first courtyard. In front of the door a large bronze gong is suspended on a wooden frame. Every citizen has the right to beat this gong, at any time, to make it known that he wishes to bring a case before the magistrate.

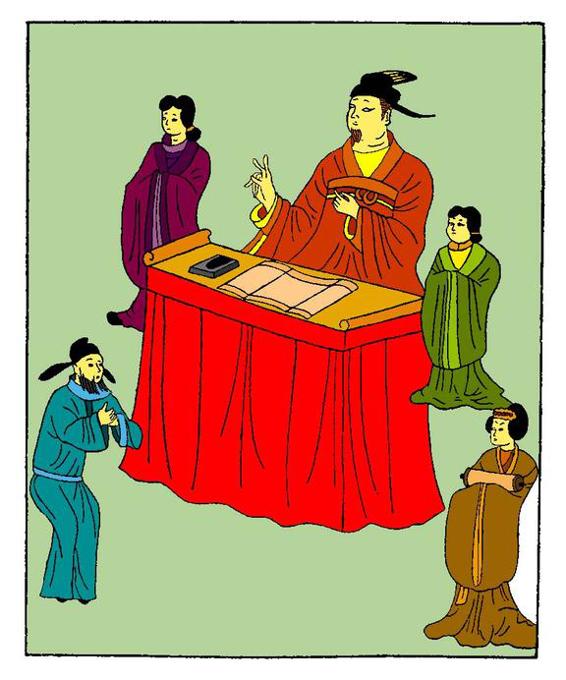

The court is a spacious hall with a high ceiling, completely bare except for a few inscriptions on the wall, quotations from the Classics that extol the majesty of the law. At the back of the hall there is a dais, raised one foot or so above the stone flagged floor. On this dais stands the bench, a huge desk, covered with a piece of scarlet brocade that entirely hides its frontside. On the table one sees a vase filled with thin bamboo tallies, an inkstone for rubbing black and red ink, a three-cornered brushholder with two writing brushes, and the seals of office, wrapped up in a piece of brocade. Behind the bench stands a large armchair, occupied by the magistrate when the court is in session. Over the dais one sees a canopy with heavy curtains, which are drawn when the session is over (see the plate on next page).

Behind this reception hall lies still another courtyard, at which we have to stop, for now we have arrived at the living quarters of the magistrate and his family. These form a small compound in themselves.

Before every session, the constables gather in the court hall, and range themselves in two rows on left and right, in front of the bench. They carry bamboo sticks, whips, handcuffs, screws and other paraphernalia of their function. Behind them stand a few runners, carrying on poles large signboards with “Silence!,” “Clear the Court!,” and such like inscriptions.

When everybody is in his appointed place, the curtains are drawn up, and the magistrate appears on the dais, clad in his official dark green robe, and with the black judge’s cap on his head. While he seats himself behind the bench, his lieutenants and the senior scribe take up their positions, standing by the side of the judge’s chair. The judge calls the roll, and the session is open.

The judge has the defendant brought in, and he has to kneel down on the bare floor in front of the bench, and remain this way for the duration of his case. Everything is calculated to impress the defendant with his own insignificance, particularly in contrast to the majesty of the law. Kneeling there far down below the judge, on a floor probably still showing the blood stains of people beaten or tortured there on a previous occasion, the constables standing over him on both sides, ready to curse or beat him at the slightest provocation, the defendant’s position can hardly be described as a favourable one. The kneeling on the stone floor is already quite unpleasant in itself, and becomes acute agony when a thoughtful constable first lays a few thin chains under the defendant’s knees, as is done in the case of recalcitrant criminals.

Since complainants, irrespective of rank or age, are placed in exactly the same position, one need not wonder that the Chinese on the whole bring a suit before the tribunal only when all attempts at effecting a settlement out of court have failed.

The law permits the judge to put the question to the defendant under torture, provided there is sufficient proof of his guilt. It is one of the fundamental principles of the Chinese Penal Code that no one can be sentenced unless he has confessed to his crime. In order to prevent hardened criminals from escaping punishment by refusing to confess, even when confronted with irrefutable proof of their guilt, various methods of severe torture, although officially forbidden by the law, have received legal acquiescence. If, however, a person should die under this “great torture,” as the Chinese call it, and it should be proved later that he was innocent, the judge and all the court personnel concerned will receive the death penalty.

Legitimate means of torture are flogging on the back with a light whip, beating on the back of the thighs with bamboo sticks, applying screws to hands and ankles, and slapping the face with leather flaps. Every bamboo tally in the vase on the bench stands for a number of strokes with the bamboo. When the judge orders a constable to beat the defendant, he throws a number of tallies on the floor, and the headman of the constables therewith checks that the correct number of blows is given.

When the accused has confessed, the judge sentences him according to the provisions of the Penal Code. This code, the history of which goes back to 650 A.D., was in force until a few decennia ago. It is a monumental work of absorbing interest, and all together an admirable example of law-making. Its merits and defects have been aptly summed up by the eminent authority on Chinese criminal law, Sir Chaloner Alabaster, in his statement: “As regards then the criminal law of the Chinese, although the allowance of torture in the examination of prisoners is a blot which cannot be overlooked, although the punishment for treason and parricide is monstrous, and the punishment of the wooden collar or portable pillory is not to be defended, yet the Code — when its procedure is understood — is infinitely more exact and satisfactory than our own system, and very far from being the barbarous cruel abomination it is generally supposed to be” (“Notes and Commentaries on Chinese Criminal Law,” London 1899).

On the whole much latitude is given to the judge’s discretion while applying the provisions of the code. He is not as strictly bound by precedent in interpretation as our judges. Furthermore the judge can have all punishments executed on his own authority, except the capital one, which must be ratified by the Throne.

As has already been remarked, a complainant’s position is as unfavourable in court as that of the defendant. Neither complainant nor defendant is allowed legal counsel; neither may they have witnesses called. The summoning of witnesses is a privilege of the court.

The only persons that in some way could be compared with our lawyers are the professional petition-writers. This is a class that is not regarded very highly in Chinese society. Usually they are students who failed in the literary examinations, and to whom the entrance to official life being thus barred, eke out a meagre existence by drawing up written complaints and defenses for a small remuneration. Some among them have quite an extensive knowledge of the law and legal procedure, and by cleverly formulating a case they often assist their client in an indirect way. But they get little credit for their labours, the tribunal ignores them, and there is no Chinese detective novel that celebrates a figure like Erle S. Gardner’s famous Perry Mason.

At first glance the above summary would give the impression that the Chinese system is a travesty of justice. As a matter of fact, however, it has on the whole worked admirably during many centuries. Although the author of our novel lived in the 18th century, and described the judicial system as he knew it in his own day, it was substantially the same system as that in operation during the Tang dynasty (618-907), the period in which the scene of the present novel is laid. During the ten centuries that intervened, even the court procedure hardly changed, which is shown by the accompanying plate, a copy of an original Tang scroll picture; the judge is seated behind the high bench, flanked by his assistants, while complainant and defendant are standing in front, below.

Literary evidence shows that the same applies to the following remarks as to how the system worked. The social structure of the 18th century does not differ in substance from that prevailing during the Tang dynasty.

The Chinese judicial system can be understood properly only if one views it against the peculiar background of the ancient Chinese government system, and the structure of Chinese society in general.

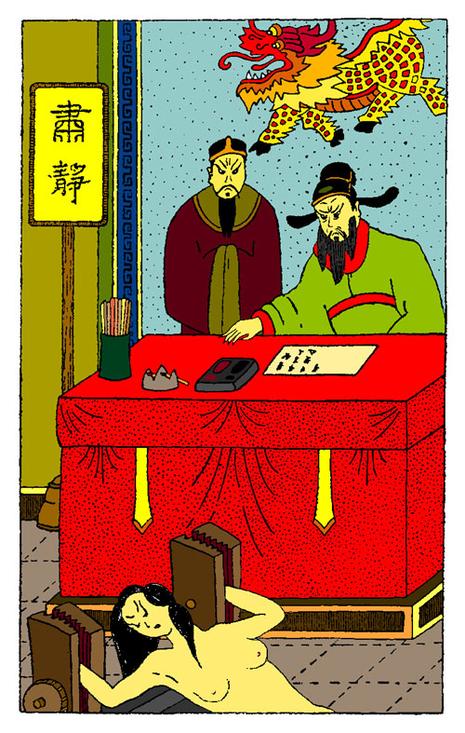

According to a very ancient Chinese conception, the souls of the dead must appear before a tribunal in the Nether World, which is an exact replica of the tribunals on earth. In front of the bench, on the left is the accused. On right is the registrar of the Infernal Tribunal, carrying a roll on which the sins of the accused are recorded. For some reason this registrar and the two attendants by the side of the judge are represented as females.

Drawing after an illustrated scroll dating from the Tang dynasty, and entitled Foo-shwo-shih-wang-djing.

It does credit to the democratic spirit that has always characterised the Chinese people, despite the autocratic form of their ancient government, that the most powerful check on abuse of judicial power was public opinion. All sessions of the tribunal were open to the public, and the entire town was aware of and discussed the tribunal proceedings. A cruel or arbitrary judge would soon have found the population against him. The teeming masses of the Chinese people were highly organised among themselves. Next to such closely-knit units as the family and the clan, there were the broader organisations of the professional guilds, the trade associations, and the secret brotherhoods. If the populace were to choose to sabotage the administration of a magistrate, taxes would not have been paid on time, the registration would have become hopelessly tangled, highways would not have been repaired; and after a few months a censor would have appeared on the scene, for the purpose of investigation.

The present novel describes vividly how careful a judge must be to show to the people at large that he conducts his cases in the right way.

The greatest defect of the system as a whole was that in this pyramidal structure too much depended on the top. When the standard of the metropolitan officials deteriorated, the decay quickly spread downward. It might have been held in check for some time by an upright provincial governor, but if the central authority remained weak for too long, the district magistrates were also affected. This general deterioration of the administration of justice became conspicuous during the last century of Manchu rule in China. One need not wonder, therefore, that foreigners who observed affairs in China during the 19th century, did not have much favourable comment on the Chinese judicial system.

A second defect of the system was that it assigned far too many duties to the district magistrate. He was a permanently overworked official. If he did not devote practically all his waking hours to his work, he was forced to leave a considerable part of his task to his subordinates. Men like Judge Dee of our present novel could cope with this heavy task, but it can be imagined that lesser men would soon have become wholly dependent on the permanent officials of their tribunal, such as the senior scribes, the headman of the constables, etc. These small people were particularly liable and most prone to abuse their power. If not strictly supervised they would engage in various kinds of petty extortion, impartially squeezing everyone connected with a criminal case. These “small fry” are wittily described in our present novel. More especially the constables of the tribunal are a lazy lot, most reluctant to do some extra work, and always keen on squeezing a few coppers here and there; yet at times surprisingly kind and human, and not without a certain wry sense of humour.

It may be added that the function of district magistrate was the stepping stone to higher office. Since promotion was based solely on actual performance, and since the term of office rarely exceeded three years or so, even lazy or mediocre persons did their utmost to be satisfactory “father-and-mother officials,” hoping in due course to be promoted to an easier post.

All in all, the system worked well. The most flagrant violations of the principles of justice recorded in Chinese history concerned cases of political and religious persecution — a respect regarding which our own record is not too clean either! Finally, the following statement by Sir George Staunton, the capable translator of the Chinese Penal Code, may be quoted here as a tribute to the ancient Chinese judicial system, all the more so since those words were written at the end of the 18th century, when the central authority, the dynasty of Manchu conquerors, was already disintegrating, and when consequently many abuses of judicial power had set in. “There are very substantial grounds for believing,” this cautious observer says, “that neither flagrant, nor repeated acts of injustice, do, in point of fact, often, in any rank or station, ultimately escape with impunity.”