Pompeii (44 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

79. With bells on ...? This extraordinary phallic lamp hung over the entrance to a bar. It provided some light at night, and must have jangled, like wind-chimes, in the breezes. The little statue in the centre is just over 15 centimetres tall.

Customers were greeted by a bronze lamp that hung over the counter on the street side (Ill. 79). This ingenious creation was so shocking to the original excavators that they chose not to illustrate it when they first published the finds. For the lamp itself is attached to a small bronze figure of a pygmy, largely naked, with an enormous phallus almost as big as himself. Although his right arm is damaged, he would probably have been holding a knife, as if making to cut off his vast penis, which is itself already growing another mini-member from its tip. To cap it all, six bells dangle from different parts of the whole ensemble. One of several such objects found in Pompeii or nearby (which is how we can be fairly certain about the knife), hanging over the counter it acted as a combination of lamp, wind-chimes and service bell. Welcome to the world of the bar?

This was a night-time, as well as a day-time world, to judge from the seven other pottery lamps found in the single room (one an elegant specimen in the shape of a foot). The rest of the objects discovered were a mixture of the practical and homely, with some little touches of luxury and whimsy. There was a good collection of bronze jars, for water or wine, as well as a bronze funnel which must have been an essential piece of equipment for decanting the wine from the storage vessels to the servers. So characteristic an accessory of the bar was it that a funnel had its place among the other drinking paraphernalia in the painted advertisement on the corner. Glass seems to have been the material of choice for drinking vessels – in general a much more common presence on Pompeian tables than we tend to imagine, misled by its relatively low rate of survival. Not only did it often smash in the eruption itself, but it has had bad luck in modern times too. Several of the glass vessels from this bar, in fact, were destroyed in the Second World War, but the finds originally included a nice set of delicate glass bowls and beakers (as well as a mysterious mini-

amphora

in glass, with a hole in the bottom, perhaps for dropping tiny quantities of special flavouring into water or wine). The utensils were completed with some cheaper pottery cups and plates and an engaging pair of jugs (one in the shape of a cockerel, the other of a fox) and a knife or two.

For the rest, there are enough surviving traces to show that the whole place was originally less bare than it appears now. Bone fittings and hinges hint at the presence of some wooden furniture, cupboards perhaps, or storage boxes. The recent takings were also discovered: 67 coins in all, a few (totalling just over 30

sesterces

) in higher denominations, the rest in

asses

, two-

as

pieces or tiny quarter-

asses

. From their exact find-spots, it seems that the counter service was mostly dealing in

asses

; a couple were even found in the

dolia

– which might hint at another use for these jars in the counter. Most of the higher denominations had been put away on the shelf behind. This amount of cash fits well with other evidence we have for the prices at a Pompeian bar. A graffito at another establishment suggests that you could get plonk (a glass? a pitcher?) for 1

as

, something better for 2

asses

and top-notch Falernian wine for 4

asses

, or 1

sesterce

(though, if Pliny is to be trusted when he says that you could set Falernian alight with a flame, then it must have been more like brandy than wine, until it was mixed with water). Apart from the welcoming pygmy, the nearest we get to any signs of depravity are the fragments of a couple of mirrors.

But it is the behaviour of the staff and customers that counts; and you cannot necessarily reconstruct the conduct within from the physical surroundings. We get a precious glimpse of the atmosphere of a bar, people and all, from two series of paintings in two other drinking establishments in the town – where the images on the walls were obviously meant to entertain the customers with scenes of the ‘bar life’ they were enjoying. Humorous, parodic, idealising, though these may be, they are our best guide to Pompeian café culture.

The first series is from the so-called Inn (or Bar) of Salvius (‘Mr Safe Haven’), a small establishment on a desirable corner site in the city centre: four images, originally running along one wall of the main front room, opposite the counter, now in the safety of the Naples Museum (Plate 13). On the left, a man and a woman – both brightly clad, she in a yellow cloak, he in a red tunic – enjoy a rather awkwardly posed kiss. Above the figures is the caption ‘I don’t want to ... [the key word is sadly lost] with Myrtalis’. Whatever the man did not want to do with Myrtalis, or who she was, we shall never know. Perhaps this is a vignette of the fickleness of passion, much the same then as now: ‘I don’t want to hang around with Myrtalis any more, I’m getting off with this girl.’ Or perhaps, given the stiffness of the pose, this girl

is

Myrtalis and the point is that the man is none too keen on the encounter.

In the next scene, a couple of drinkers are getting served by a waitress, but there’s competition for the wine. One of them is saying, ‘Here’, the other, ‘No it’s mine.’ The serving woman isn’t going to get involved: ‘Whoever wants it, take,’ she says to them. Then, as if to taunt them by offering it to another customer, says, ‘Oceanus, come and have a drink.’ This is not deferential service; and the waitress is more than ready to answer back. Drinking is followed by a game of dice in the next scene, and another argument is brewing. A couple of men are sitting at a table. One shouts, ‘I’ve won’, while the other objects, ‘It’s not a three, it’s a two.’ By the final scene in the series, they have come to blows and abuse: ‘You scum, I had the three, I won’, ‘No, come on, cocksucker, I did.’ It is too much for the landlord, who throws them out. ‘If you want to fight, go outside,’ he says in the usual landlord’s way. The customers, as they looked at the paintings, were presumably supposed to get the message.

The paintings suggest a familiar and slightly edgy mixture of sex, drink and play, but no terrible moral turpitude: some kissing, plenty of tipsy banter (but hardly the vomiting we saw in the dining-room images), a row over a game getting a bit out of hand, and a landlord who doesn’t want his bar trashed. We find much the same kind of pictures in the other decorated bar a few blocks away, also on a good corner site and usually now called after its location, the Bar on the Via di Mercurio. This had a back room with a direct entrance onto the street, and presumably waitress service from the counter next door to four or five tables, maximum. It was on the walls of this room that the paintings were set, at just the right height to be enjoyed by someone sitting at a table. There are captions to some of them, not here painted as part of the original design, but graffiti scratched on by the customers.

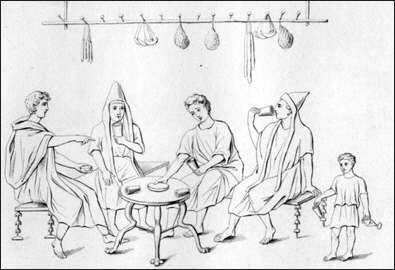

80. Life in the bar. This nineteenth-century drawing shows four men around a table, enjoying a drink, served by a diminutive waiter. Above them hang some of the bar’s food supplies.

Once again we find men (this does seem to be a world of

male

drinking) having their glasses replenished by willing, or not so willing, servers. In one painting a waiter (or waitress, it’s hard to tell) is topping up a glass that a customer holds out. Someone has scratched above his head ‘Give me a little cold water’ – to mix, that is, with the wine in the glass. In another similar scene, the scrawled caption reads: ‘Another cup of Setian’, referring to the wine that had been the favourite of the emperor Augustus, and was reputed to be especially nice when chilled with snow. There are scenes of gambling here too (Plate 6), and one particularly evocative view of the inside of a bar (Ill. 80). A group of what seem to be travellers (a couple are wearing distinctive hooded cloaks) are sitting round a table having a meal. Above them is one solution to the storage problem in these small places: a selection of food, including sausages and herbs, hangs from nails attached to a shelf, or even to some kind of framework suspended from the ceiling.

But there is a strikingly different theme in a painting that once decorated the end wall of this room, long since lost or destroyed (all except a couple of remaining human feet and shins), and known only from nineteenth-century engravings (Plate 11). It apparently shows an extraordinary balancing act. A man and an almost naked woman perch on a pair of tightropes, each holding or drinking from a large glass of wine. And as if that wasn’t difficult enough, the man simultaneously inserts his large penis into the woman from behind. In fact, it is something of a relief to discover that the original picture was not quite as weird as this engraving makes it seem. For more than likely the whole tightrope element was introduced by the modern artist, who mistook the faint traces of the painter’s guidelines, or possibly painted shadows, for this ingenious contraption. But even minus that particular bit of the balancing act, it is a provocative contrast to the decorous kiss from the other bar. What does it represent? Some archaeologists have thought it a scene drawn from a raunchy act in the local theatre (and so the large penis might be a pantomime-style appendage). Others, bearing in mind that the companion pictures are all of tavern life, conclude that this must be one of the activities you would find in the bar itself – whether it’s a do-it-yourself cabaret, or something the drinkers might end up doing (or hope to end up doing) with the barmaids by the end of the evening.

Does this painting suggest that we should take the accusations of Roman writers more seriously? Certainly, in addition to the eating and drinking, gaming and flirtatious banter, there are many hints that the sexual encounters in at least some of these bars went beyond kissing. On the outside wall of one bar, for example, a small graffito (written entirely within a large letter O of an electoral slogan) reads: ‘I fucked the landlady’. In others, we find women’s names written on the wall in a clearly erotic context and sometimes with a price: ‘Felicla the slave 2

asses

’, ‘Successa the slave girl’s a good lay’, and even what has been taken to be a price list, ‘Acria 4

asses

, Epafra 10

asses

, Firma 3

asses

’.

We have to be careful in interpreting this kind of material. If today we were to see ‘Tracy is a whore’ or ‘Donna sucks you off for a fiver’ daubed up at a bar or bus shelter, we would not automatically assume that either of them was actually a prostitute. Nor would we assume that ‘a fiver’ was an accurate reflection of the prices charged for these sexual services in the area. They are just as likely to be insults as facts. So too in Pompeii – despite the attempts by some over-optimistic modern scholars to use evidence like this to construct lists of Pompeian prostitutes or even to work out an average price for the job. In fact that ‘price list’ may be nothing of the sort. The inclusion of

asses

is a modern addition; the original has simply three names with a number.

Yet the clustering of explicitly erotic scribble around some bars cannot be explained away, especially when it is combined with matching decorations. It has led to the conclusion that, while some drinking establishments in the town were just that, with a bit of sex on the side, some were not so much bars as fully fledged brothels. Both the bar on the Via dell’Abbondanza that we looked at and the Bar on the Via di Mercurio have often been identified as such: the first largely on the basis of the pygmy lamp, the second on the basis of the tightrope walkers (and perhaps another painting of which only a head survives, but which might originally have shown a couple making love). On some recent calculations, these are just two of a grand total of thirty-five brothels in the town. Pompeii, in other words, was a town in which there was roughly one brothel for every seventy-five free adult males. Even adding in the visitors, the country dwellers and the slaves who might have chosen to spend their pocket money in that way, it seems at first sight an over-generous ratio – or a level of sexual supply that would justify the worst fears of Christian moralists about pagan excess.

That, in a nutshell, is the ‘Pompeian Brothel Problem’. Can we really believe that there were as many as thirty-five brothels in this small town? Or was there, as the most sober estimates have it, just one? How do we recognise a brothel when we find one? How do you tell the difference between a brothel and a bar?

Visiting the brothel

Roman sexual culture was different from our own. Women, as we have seen at Pompeii, were much more visible in the Roman world than in many other parts of the ancient Mediterranean. They shopped, they could dine with the men, they disposed of wealth and made lavish benefactions. Yet it was still a man’s world in sex as it was in politics. Power, status and good fortune were expressed in terms of the phallus. Hence the presence of phallic imagery in almost unimaginable varieties all round the town.