Postcards (25 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

‘Several things almost simultaneously. Exultant, exultancy because I hit a bird, because I have killed this elusive – thing – that I hunted. I am glad, you see, triumphant, in a small way. And of course I feel sorrow too, that this fine being, with its private life and pleasures is dead. I feel guilt that it is I who has terrified it, who has killed it. And I feel anger, anger against a possible someone who might say to me, “That was a despicable act. Couldn’t you let the bird live? Couldn’t you sublimate your blood lust with a camera or a sketch pad?” No

one has said this to me yet, but I am preparing my response, you see. Then too, I feel anticipation for the dinner and the praise of the dinner guests, “Oh, you have shot this wiry bird all by yourself? How intense!” And let me ask you, how do

you

feel about shooting birds?’

‘Nothing. I feel nothing.’ His sense was for the place, and the birds meant as much to him as wild mushrooms, nothing in their singularity, everything as a part of the whole. A cold confusion was invading him against his will. A coldness toward his life.

He no longer cared for his family. Here, here at the hunting camp was the kernel of things. Here was Larry who knew of the violated cities, the packed trains, those other kinds of hunting camps as well as he. The places for killing. It was Larry who found the way through miles of brush, who kept his senses while cutting obliquely across the stone-mangled ridges. Witkin was off-balance with every step.

He caught his breath at the raw brown of fungus, the radiant bark, at shattered quartz, leathery flap of leaves, split husks. O gone, he thought, gone the constricted world of metal table and desk and human integument, the breath foul with fear, the nose swelling with cancer, Mrs. MacReady’s toes humped inside her white shoes, treading the carpet. He shuddered at himself, at his cold self, his dulled tone, his hands in the sink like two hairless animals crawling over one another, the antiseptic soap jetting out, the sleek pages of medical texts, the photographs of deliquescing flesh, the dinner table, the vacuity of Matitia and the children like the children of someone else, their features and habits drawn from some other source than himself.

Only the half brother understood the atavistic yearning that swept him when he stood beneath the trees, when a branch in the wind made the sound of an oboe. He had only to walk into the woods far enough to lose the camp, and he was in an ancient time that lured him but which he could not understand in any way. No explanation for his sense of belonging here. He stared, numb with loss, into bark crevices, scrabbled in the curling leaves for a sign, turned and turned until the saplings heaved their branches and the trunks tilted away from him. He could hear a little drum, a chant. But what could it mean? The kernel of life, tiny, heavy, deep red in color, was secreted in these gabbling woods. How could he understand it?

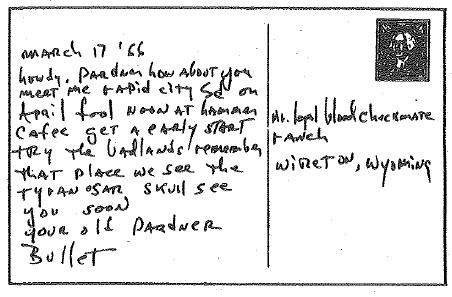

BULLET SAID THAT that the student with the wire-rimmed glasses had choked to death on his own vomit. Horsley had written a letter about it.

‘Yessir. Wind blew his pilot light out, that’s for sure. He got running with a rock-and-roll dope crowd, dress up in dirty tablecloths and beat on tambourines all night. Got drugged out, layin’ on his back, throwed up and choked to death, says Horsley. Dirty hippies, ought to shoot ’em, every one. But you know what, Professor Alton Cruller wants to come out and dig swamps for duckbills this summer. Cruller is big. He’s very, very big. Got an idea about a death star that could have wiped ’em out at the end of the Cretaceous.’

Why the hell, thought Loyal, did it always turn into a mess? His tongue went to the place where the abscessed tooth had been. He’d liked Crazy Eyes, liked his intensity and his peculiar humor. The plan to work together on the big projects, mapping all the known track sequences, taking casts and photographs that would prove dinosaur agility and speed – the hell, it was down the drain now. The closest he’d ever come to doing something of value. He didn’t give a shit about Cruller.

And after two weeks out with Bullet it seemed he’d had enough of the bones. It had gone flat. Bullet wanted skulls and femurs. It was the tracks that excited Loyal and without Crazy Eyes the search didn’t have a focus. He was restless, as if the news of the student’s death had triggered some migratory urge.

‘I guess it’s time, Bullet. I was thinking about it last year. I’m going to move on, do something else for a while.’

‘What the hell for? We’re just getting good. What the hell you gonna do that can beat this? Your own hours, good money, most interesting work there is. You love it, I always knew you loved it. We’re a good team, you bastard.’

‘I know it.’ But he wouldn’t miss Bullet the same way he missed Crazy Eyes. He had hardly known him, but he still had the drawing of the duckbill running over the creased paper. Not a swamp in sight.

30

The Troubles of Celestial Bodies

THE CABIN, eighteen miles north of the ranch they’d bought in the fifties, was where he came, Ben said, to drink. So Vernita would be spared the sight of the crawling sot she had married.

The sot was short with broad shoulders and a chest like a kettledrum. On his head a springy mass of white hair. The dulled eyes in their heavy hammocks of flesh were as incurious as those of a street musician, yet Ben’s face still held a young man’s freshness, perhaps because of the red smiling mouth. There were the pointed arches of the upper lip, the curving nostril with its thready veins. Anyone could tell. His voice was hypnotic, Russian in its darkness.

‘How I came to get the cabin dates back to the time when I was

seeking a place suitable for a little observatory. You’ve heard me talk about that before, Loyal. I was looking for good darkness, smooth air. Vernita wanted room – some lab space, a study where she could write, a big kitchen. Had to have a good view of course.’ His words marched out in the amused basso, his fingers twisted an absent cork. ‘We found the ranch and it worked quite well at first. Vernita was gone all summer studying jellyfish in the Sea of Cortez. Came back in the fall to write and I was damn glad to see her. While she was gone I’d put a hole in the roof of the equipment shed for a temporary observatory and mapped out a couple of places where the main observatory could go. But Loyal, my friend, then I’d start to drink. After a week of it I’d sober up and work for a month and then it would all fall apart again. I had a pattern. I don’t know what you know about astronomy, but I’ll tell you something, you can’t make accurate observations and you can’t keep good records if you’re drunk. Record-keeping is the heart and soul of astronomy. If the records are broken, what good are they?’ The finger wagging, ticking off the reasonable points. Loyal had to agree.

‘But I worked it out in my cunning wet brain that if I was consistently haywire and did meticulous work in the sober periods the records would still have some value because there’d be regularity to them. That’s my rationalization. That’s how I work. My work is flawed, but it’s a consistent flaw.’ The smile slyer now. ‘When Vernita is around now I work it another way. I go to the cabin. As you know. Or I go down to Mexico City. As you know.’ The voice dropping, whispering, confiding. ‘Bought the cabin before the war. Been coming up here ever since when the sailor’s home from the sea. Periodically. Consistently. With a pattern.’ That boiling smile.

He started as soon as the cabin was in sight, as though he had crossed a boundary into a more permissive country. The bottle came out of his shirt pocket, the pocket over his heart, his heart’s desire. He tipped it back and let the whiskey flower in his throat. The long exhalation was mostly relief, a little pleasure.

‘Leave the door open,’ he said to Loyal. From inside the dark log cabin the golden landscape filled the doorway. The wind was the color of fire.

‘Have a drink. You come this far with me you might as well go the whole distance. Some kind of landmark. I never needed anybody to pick me up before this year. The clock is ticking out.’ The knotted hand, pouring, was steadier than Loyal had seen it in weeks, the blue hammer mark across the fingers showing purple. Drinks to keep his balance, Loyal thought. The wind swayed the plank door.

A wooden floor, log walls, the table, a bench, a single chair, a few chipped jelly glasses and tea mugs. No beds. Just roll up in your sleeping bag on the floor, or fall down and pass out where you dropped.

Ben stared through the open door at the writhing grass, the rocks and dust-ghosts; perhaps he was memorizing the horizon, the knotted mountains or the clouds like white flames from a celestial burner. A wedge of weather was moving toward them. He sat on the bench and leaned on the table. Still looking out the door he poured and poured again, he drank, smiling into the glass, he remarked that the wind was coming up, talked to Loyal, then to himself, and still he drank, slowly now, sipping careful mouthfuls of an amount he knew was right. The onerous bands loosened. The wind moaned.

‘You know,’ he said, ‘you can get so used to silence that it’s painful when you hear music again.’ Through the wind Loyal could not remember any music he had ever heard. The wind became all the music since the beginning. It disallowed musical memories. He tried to think of the tune of ‘Home on the Range’, but the wind took everything. It whined in three different voices at once, between-the-teeth screaming at the corners of the cabin, around the woodpile, and away into the night and back again on a great moaning circle.

Ben sloshed whiskey into the cracked glasses.

And the skies are not cloudy all day, hummed Loyal to himself, following the wind’s bleak tune.

‘I’m one of the remnants of a dying species, the amateur astronomer.’ The voice roared, ‘I am not owned by a university. I do not depend on the publication of articles packed with incomprehensible mathematical formulas for my advancement through life. I go to no National Association of Astronomers meetings. But I pay! I pay a price for my ability to think freely! I do not get time at a big telescope! My amateur status bars me from the big ones! (The academics stand

in line for years to use them.) I make myself content with what I can have and they cannot. And I’ve had a modest success. But the day is coming if not already here when there will be no place for the amateur astronomer except pointing out the moon at backyard barbecues or enviously applauding the coups of the technologically aided. It sounds like sour grapes? No. Nothing stopped me from the academic route. Except, perhaps, the depression, the war and my little hobby. That was a long time ago. I’ve had this little hobby for a long time. I was actually in graduate school and on my way, but the clubby gangism ate me out like acid. Do you know what I mean? The ones who play golf. And of course I was already a drunk. I hated the slap on the back, the favors for friends, the internecine feuds and fumed oak skulduggery. I spent five years in the Navy where, of course, none of these evil situations exist. The saintly Navy! When I got out I was ready for something new and married Vernita, quite ready to play the husband and father. I have not had a starring role in either part. What saved me – or ruined me – was an inheritance. It allowed me to be what I really am, a cantankerous alcoholic who has occasional moments of lucidity when he can see far and deep into the way things work, the clocks of the heavens, the petty straw-tuggings of men and women.’ The red mouth moved around the words, the brain shuddered in its skull.

‘Loyal, my friend. We get along, you and me. We make a damn good observatory.’ The hand poured, the face cracked in the egg-yolk light. The shadow of the door pointed into the room, the room fell into a pit.

‘We are losing the sky, we have lost it. Most of the world sees nothing above but the sun, conveniently situated to give them cancerous tans and good golf days. The stinking clods are ignorant of the Magellanic cloud. They know not the horsehead nebula, the collars of Saturn like metal coils around the neck of a Benin princess, the vast black sinks of imploded matter like drain holes in outer space, the throbbing light of pulsars, atomizing suns, dwarf stars heavy beyond belief, red giants, the uncoiling galaxies. I am not talking about the jingoistic bus ride to the moon or the doggies woofing in weightless capsules among the planetary detritus, the petty and costly face slaps

of the pudding powers. Think about it, Loyal, nations as puddings. No, the study of space unwraps the strangest and most exotic realities the human mind can ever encounter. Nothing seems impossible in space. Nothing is impossible. All is strange and wondrous in that nonhuman void. This is why astronomers do not seek the company of any but their fellows, for no one else has seen the mysteries as they have. Theirs is a ghastly joy felt in exploding stars, in galactic death. They know the dim light of a star filtering through our filthy, polluted sky has been on its way to that moment for a thousand years.’