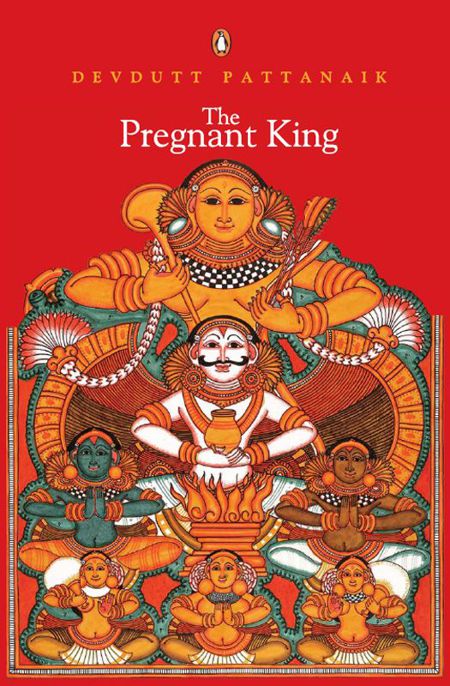

Pregnant King, The

Read Pregnant King, The Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

The Pregnant King

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Dr Devdutt Pattanaik is a medical doctor by training, a marketing consultant by profession, and a mythologist by passion. He has written and lectured extensively on the nature of sacred stories, symbols and rituals and their relevance in modern times.

Devdutt’s books include

Shiva: An Introduction

(VFS, India),

Vishnu: An Introduction

(VFS, India),

Devi: An Introduction

(VFS, India),

Hanuman: An Introduction

(VFS, India),

Lakshmi: An Introduction

(VFS, India),

Goddesses in India: Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine

(Inner Traditions, USA),

Indian Mythology: Stories, Symbols and Rituals from the Heart of the Subcontinent

(Inner Traditions, USA),

Man Who Was a Woman and Other Queer Tales from Hindu Lore

(Haworth Publications, USA),

Shiva to Shankara: Decoding the Phallic Symbol

(Indus Source, India), and

Myth=Mithya: A Handbook of Hindu Mythology

(Penguin, India).

The Book of Kali

(Penguin, India) is based on his talks.

The unconventional approach and engaging style evident in Devdutt’s lectures, books and articles also extends to this, his first work of fiction. Devdutt is based in Mumbai. To know more visit

www.devdutt.com

Yuvanashva, the pregnant king

- his great grandfather, Chandrasena

- his grandfather, Pruthalashva

- his father, Prasenajit

- his mother, Shilavati, princess of Avanti

- his first wife, Simantini, princess of Udra

- his second wife, Pulomi, princess of Vanga

- his third wife, Keshini, the potter’s daughter

- his first son, Mandhata

- his second son, Jayanta

- his teacher, Mandavya

- his friend, Vipula, son of Mandavya

- his doctor, Asanga, son of Matanga

- his sorcerers, the Siddhas, Yaja and Upayaja

- his foster children, the ghosts, Sumedha and Somvati

- his daughter-in-law, Mandhata’s wife, Amba

- his daughter-in-law’s mother, Hiranyavarni

- his daughter-in-law’s father, Shikhandi

- his daughter-in-law’s aunt, Draupadi

| In the Mahabharata | In this story |

|---|---|

| Pandavas and Kauravas, the Kuru princes of Hastina-puri, defeat Drupada, king of Panchala, and give one half of his kingdom to their teacher, Drona | Birth of Prasenajit, prince of Vallabhi |

| Drupada gets his son, Shikhandi, married to Hiranyavarni, princess of Dasharni | Prasenajit marries Shilavati, princess of Avanti |

| Pandavas marry Drupada’s daughter, Draupadi, and demand from the Kauravas one half of their inheritance on which they establish the kingdom of Indra-prastha | Shilavati gives birth to Yuvanashva |

| Kauravas defeat Pandavas in a gambling match and send them into exile in the forest for thirteen years | Yuvanashva’s first marriage |

| After the priod of exile, Kauravas refuse to part with Pandava lands and wage war against them at Kuru-kshetra | Yuvanashva invites Yaja and Upayaja to conduct a yagna |

| Birth of Parikshit, grandson of the Pandavas | Birth of Mandhata |

| Renunciation of the Kuru elders | The marriage of Mandhata |

They came like ants to honey. Warriors. Hundreds of warriors. Every self-respecting Kshatriya in Ilavrita, led by conch-shell trumpets, followed by a vast retinue of servants, wearing resplendent armour, bearing mighty bows, on elephants, on chariots, on foot, through the darkest nights and the coldest days of the year, along the banks of the Ganga, the Yamuna and the Saraswati, to the misty plains of Kuru-kshetra.

They came like ants to honey. Warriors. Hundreds of warriors. Every self-respecting Kshatriya in Ilavrita, led by conch-shell trumpets, followed by a vast retinue of servants, wearing resplendent armour, bearing mighty bows, on elephants, on chariots, on foot, through the darkest nights and the coldest days of the year, along the banks of the Ganga, the Yamuna and the Saraswati, to the misty plains of Kuru-kshetra.

They came, the young and the old, the adventurous and the inexperienced, to fight the Pandavas, or the Kauravas, or for dharma. Drupada came because he wanted to settle old scores. Shikhandi because he could not escape destiny. Some came obliged by marriage. Others because death in Kuru-kshetra guaranteed a place in Amravati, the eternal paradise of the sky-gods.

Many came for the glory. For this was no ordinary war. It would be the greatest battle ever fought over property and principle in the land of the Aryas. A battle of eighteen armies. Bards would sing of it long after the last warrior had fallen. This war would make heroes of men.

Soon banners of every king and kingdom fluttered along the horizon. Banners of Yudhishtira and Duryodhana, Bhima and Bhisma, Drona and Drupada,

Karna and Arjuna. Banners from Gandhara, Kekaya, Kosala, Madra, Matsya, Panchala, Chedi, Anga, Vanga, and Kalinga.

Alas! There was no banner from Vallabhi.

Yuvanashva, the noble king of Vallabhi, son of Prasenajit, grandson of Pruthalashva, great grandson of Chandrasena, scion of the Turuvasu clan, wanted to come. ‘Not for glory, not to settle any score, not out of a sense of duty either,’ he clarified to the Kshatriya elders, ‘but to define dharma for generations to come is why I wish to go. Long have we have argued: Who should be king? Kauravas or Pandavas? The sons of a blind elder brother, or the sons of an impotent younger brother? Men who go back on their word, or men who gamble away their kingdom? Men for whom kingship is about inheritance, or men for whom kingship is about order? What could not be agreed by speech will now finally be settled in blood. All the kings of Ila-vrita will participate. I must too.’

Yuvanashva had raised an army, filled his quivers, fitted his chariot and unfurled his banner. He had then gone to his mother, the venerable Shilavati, to seek her permission.

Widow since the age of sixteen, Shilavati had been the regent of Vallabhi, and custodian of her son’s kingdom for nearly thirty years. She sat in her audience chamber on a tiger-skin rug, dressed in undyed fabrics, no jewellery except for a necklace of gold coins and tiger claws, and a vertical line of sandal paste extending from the bridge of her nose across her forehead. She looked as imperious as ever.

Placing his head on his mother’s feet, his heart full of excitement, Yuvanashva had said, ‘Krishna’s efforts to

negotiate peace between the cousins have collapsed. The division of the Kuru clan is complete. The five Pandavas have declared war against their hundred cousins, the Kauravas. The sound of conch-shells can be heard in the eight directions. It is a call to arms for every Kshatriya. This is no longer a family feud; it is a fight for civilization as we know it. Grant me permission so that I can go.’

It was then that Shilavati’s affectionate hand on her son’s head stilled. ‘Go, if you must,’ she said, her voice full of disapproval. ‘Noble causes are noble indeed. But that is their story. I am interested only in yours. Should you die in Kuru-kshetra, my son, fighting for dharma, you will surely go to the realm of the Devas covered in glory. There, standing on the other side of the Vaitarni, you will find your father, your grandfather, your great grandfather and all the fathers before him. These Pitrs will ask you if you have done your duty, repaid your debt to your ancestors, fathered children through whom they hope to be reborn in the land of the living. What will be your answer then?’

Yuvanashva’s heart sank. He had no answer. Thirteen years of marriage, three wives and nothing to show for it.

All dreams of a triumphant return faded in the winter mist. His mother was right: what if he died? Behind him would be an abandoned kingdom, an abandoned mother and three abandoned wives. Before him would be unhappy ancestors, like cawing crows, refusing to let him enter the land of Yama. What would be actually achieved? Glory? Dharma?

So he took a decision. ‘I will not go. Not until I father a son.’

‘But this is what you have always wanted: your one chance to be like your illustrious ancestors—like Turuvasu, like Yayati, like Ila before him,’ said his friend, Vipula, when Yuvanashva returned to his mahasabha, his disappointment evident. ‘You could return alive, triumphant, with the courage to march to every corner of the world, be lord of the circular horizon and declare yourself Chakra-varti.’

‘What kind of a Chakra-varti will I be, what kind of dharma will I establish if I let myself be driven by desire? I have a duty towards my subjects, my wives, my ancestors, and my mother,’ said Yuvanashva, trying hard to convince himself.

‘Can’t you see what your mother is doing? You have been consecrated as king by the Brahmanas. It is your destiny, your rightful inheritance. Yet she will not let you rule because you have no children. She will not even let you fight because you have no children. Your mother has turned your masculinity against you and clings to the throne like a leech.’

Yuvanashva defended his mother, ‘My mother is doing what she was brought to Vallabhi to do: rule the kingdom after becoming a widow….’

‘Only until you were ready to be king,’ interrupted Vipula.

‘I am not ready. I am not yet father. A king must provide proof of virility before he can rule.’

‘Who says so?’

‘My mother says so.’

Vipula’s heart went out to his friend. ‘Love for your mother blinds you, my king. You could have been great. But you settle for being good.’

‘I have no choice, Vipula,’ said Yuvanashva, a wistful smile on his lips.

And so for eighteen days, while eighteen armies would spill blood on the plains of Kuru-kshetra, Yuvanashva would stay in Vallabhi with his wives, struggling to win a battle he had fought for a long, long time. Until he fathered a child, his mother would not let him rule Vallabhi and his ancestors would not let him cross the Vaitarni.