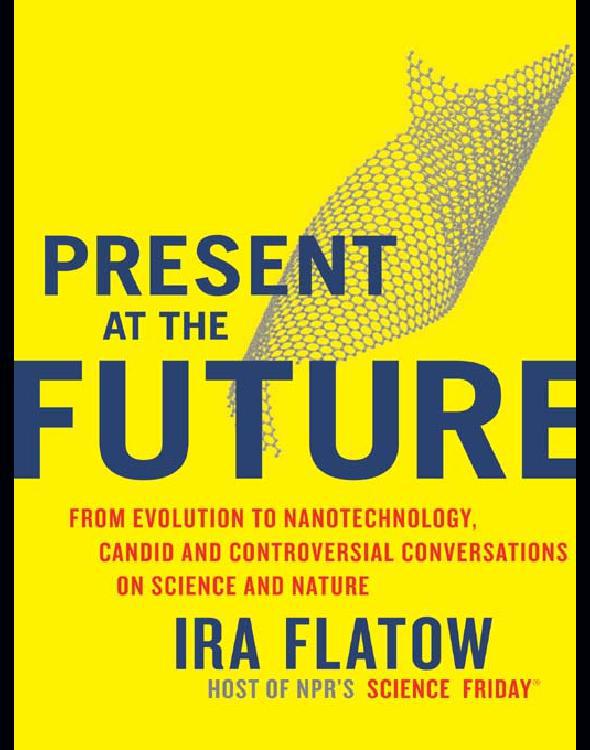

Present at the Future

Read Present at the Future Online

Authors: Ira Flatow

PRESENT AT THE FUTURE

FROM EVOLUTION TO NANOTECHNOLOGY, CANDID AND CONTROVERSIAL CONVERSATIONS ON SCIENCE AND NATURE

IRA FLATOW

CONTENTS

PART I THREE POUNDS OF GRAY MATTER

Chapter 2

Memory:

Senior Jeopardy!,

Anyone?

Chapter 3

Oliver Sacks: Music Makes the Memory

Chapter 4

Pathways of Addiction

Chapter 5

Sleep and Learning: Caffeine in Your Beer

Chapter 6

Where the Very Big Meets the Very Little

Chapter 7

It’s a Dark World After All

Chapter 8

String Theory: We Have a Problem

PART III GETTING READY FOR GLOBAL WARMING

Chapter 9

Is Every Coastal City a New Orleans Waiting to Happen?

Chapter 10

The Moral Imperative

PART IV ENERGY: WHICH WAY TO GO?

Chapter 11

It Makes Your Hair Hurt

Chapter 12

Forests and Fields of Alcohol

Chapter 15

The Wind Rush Is On!

Chapter 16

The New Small Is Big

Chapter 17

There’s No Business Like Space Business

PART VII THE OCEANS ARE IN TROUBLE

Chapter 18

Sylvia Earle: Sounding the Alarm

Chapter 19

Craig Venter Goes Fishing for Genes

PART VIII SCIENCE AND RELIGION

Chapter 20

Fitting God Into the Equation

Chapter 21

Evolution: Still Under Attack

Chapter 22

The Dover School Board Case

PART IX PIONEERS PRESENT AT THE FUTURE

Chapter 24

Ian Wilmut: Dolly Plus Ten

Chapter 27

The Universe as Computer

Chapter 29

The Case of the Mice Cured of Diabetes

Chapter 30

The Misbehaving Shower Curtain

Chapter 31

Why an Airplane Flies: Debunking the Myth

Chapter 32

The Great Champagne Bubble Mystery

PART XII THE QUEST FOR IMMORTALITY

Chapter 34

Stem Cells, Cloning, and the Quest for Immortality

One of the joys of being a science journalist is the “aha!” moment. That brilliant flash of light, that moment of epiphany, when all the cylinders in your head click and you come to understand something you had never understood before. Sometimes your mouth may actually fall open as your eyes wander around the room, not really seeing anything but not under conscious control of your brain, which has just latched on to an idea that had eluded it for quite some time.

As I say, one of the joys of being a science journalist, especially the host of a popular radio program such as Science Friday, is the ability to share that moment with millions of others. And one of those moments, among many others, stands out in my mind. It involves solving a problem I was having with one the most widely accepted “truths” about the world around us: why airplanes fly.

Like every science journalist who ponders how things work, I was more than casually acquainted with the commonly accepted ideas about the physics of flight. After all, the explanation for why airplanes fly is one of those unquestioned beliefs in science education, a dogma that has been repeated for generations and taught in eighth-grade science class along with why the sky is blue. (Oh, you were out that day?) In fact I have mouthed the simple explanation countless times on radio and television talk shows. I had sung its praises in my own (previous) books. High-school teachers who coach

award-winning teams in science competitions would all say the same thing: “The basis for why airplanes fly is a concept in physics called Bernoulli’s principle. We all know that.” No-brainer. Period. End of discussion.

Just what is Bernoulli’s principle? It’s quite simple to state: Daniel Bernoulli, a Swiss mathematician, discovered in 1733 that the faster a fluid flows, the lower its pressure.

And that explanation has been used ever since the 1930s to explain why an airplane flies. In short, the explanation states that because of the design of a wing, air will fly faster over the top than the bottom. According to Bernoulli, faster-flowing air on top means less pressure on top. More pressure on the bottom than on the top lifts the wing. So the wing is literally sucked up into the sky, the same way you suck up soda in a straw. Complex science-fair projects and even simple strips of paper over which you blow—the paper flies up—have been used for decades to demonstrate Bernoulli’s principle. And as I say, I too, when asked to explain in simple terms what makes an airplane lift off the ground, would say the same thing: Bernoulli’s principle.

That all came to an end one day in 1989. After that day, I would no longer freely mention Bernoulli and flight in the same breath, unless it was to denounce the principle. Because on that day I met a man who would change my life forever. And I vowed to set the record straight.

I had just finished making a speech to a group of folks at a science conference at the University of Vermont. After polite applause and a brief question-and-answer period, people began to file out. Just as I was about to collect my papers and head for the door, the real answer to why airplanes fly appeared before me in the form of Norman Smith. Norman Smith had spent more than two decades as a research aerodynamicist for NASA and before that for its pre-space predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. He was the author of more than a dozen science books as well. And now in his later years, after a very successful career in aviation, he was on

a one-man crusade: to get rid of Bernoulli’s principle as the explanation for why airplanes fly.

“I listened to your speech and was very impressed with what you had to say,” said Smith. “Except for one thing. That explanation about why airplanes fly.”

“Oh. Did I say something wrong?”

“Yes, you did. That explanation you gave, the one using Bernoulli’s principle, is no longer acceptable. It’s old and not really accurate.”

Smith was trying to be polite. What he would have really liked to have said, I think, was “You dummy, get with the program. Here’s another guy I’m going to have to reeducate.”