Prisoners of the North (22 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The Arctic Council during the Franklin search. The object of that search is portrayed in a painting in the background

.

—THREE—

John Rae was in no sense a Royal Navy man. The Orkney-born physician and explorer for the Hudson’s Bay Company was one of the few people who believed that Franklin had turned south and not north, as the majority insisted. In his view, Franklin was to be found well west of Boothia Felix in the vicinity of King William Land. This was uncharted territory. Nobody knew whether Boothia was an island or a peninsula; the same uncertainty applied to King William Land. In April 1854, Rae led a small party of six in a trek across the neck of Boothia, which turned out to be a peninsula. On the return trip he was able to establish that King William Land was indeed an island. The stretch of water between the two, now known as Rae Strait, was an alternative part of the Northwest Passage, but Franklin would have had no way of knowing that.

On April 21, at Pelly Bay on Boothia, Rae met a party of Inuit who told him a tale that would eventually be worth ten thousand pounds to him and his men. They had heard stories from other natives about thirty-five to forty men who had starved to death some years before to the west of a large river, perhaps ten or twelve days’ journey away. Rae had no idea who the men were, and since his job was to chart the Arctic coast for the Company, he got on with it. But at Repulse Bay that fall, several Inuit gave him more details about the dead men, and Rae soon realized that their bodies must have been found near the mouth of the Great Fish River—the very spot that the persistent Dr. King had argued the Franklin Party would head for and the very spot for which Jane Franklin herself had tentatively but unsuccessfully advocated.

Rae’s report to the Admiralty was a shocker. “I met with Esquimaux in Pelly Bay from one of whom I learned that a party of ‘white men’ (Kabloonans) had perished from want of food some distance to the westward.… Subsequently further particulars were received, and a number of articles purchased, which places the fate of a portion (if not of all) of the then survivors of Sir John Franklin’s long-lost party beyond a doubt; a fate as terrible as the imagination can conceive.…”

Rae would not bring himself to use the word “cannibalism” in his report, but he certainly made it obvious. The Inuit had walked among the bodies and the scattered equipment of the expedition, and “from the mutilated state of many of the corpses, and the content of the kettles, it is evident that our miserable countrymen had been driven to the last resort.…”

Rae did not publicize his findings, but the Admiralty distributed his report to the press. A vast public controversy ensued, with Rae the villain—a clear example of shooting the messenger. The real impact of Rae’s report was that it demolished the universally held image of Arctic explorers as noble and highly moral creatures, unsullied by any human weakness. In

Household Words

, the periodical that Charles Dickens had launched in 1850, a contributor wrote that the narratives of the naval explorers “supply some of the finest modern instances of human energy and daring, bent on a noble undertaking, and associated constantly with kindness, generosity, and simple piety. The history of Arctic enterprise is stainless as the Arctic snows, clean to the core as an ice Mountain.” He ended his essay with these words: “Let us be glad … that we have one unspotted place upon this globe of ours; a Pole that, as it fetches truth out of a needle, so surely also gets all that is right-headed and right-hearted from the sailor whom the needle guides.”

Rae’s report was based on hearsay evidence, and the public, clutching at that straw, simply refused to believe that Englishmen would eat each other.

The Times

expressed the prevailing sentiment: “All savages are liars.” Rae was excoriated because he had stood up for the natives, insisting that their stories were believable. The controversy cost him a knighthood. Dickens entered the lists in his own periodical when he described the Inuit as “Covetous, treacherous and cruel … with a domesticity of blood and blubber.” He simply did not believe,

could

not believe, that “the flower of the trained adventurous spirit of the English navy, raised by Parry, Franklin, Richardson and Back,” had descended to what was the most dreadful crime in the Victorian mind. “It is in the highest degree improbable that such men would, or could, in any extremity of hunger, alleviate the pains of starvation by this horrible means.” But later evidence found on or near King William Island was to establish incontrovertibly that cannibalism had occurred among Franklin’s crew.

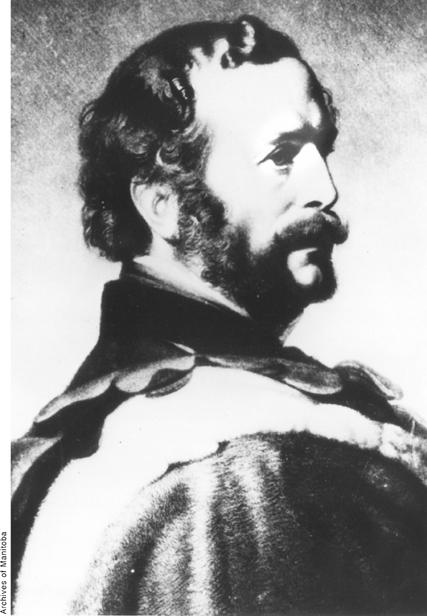

John Rae, with the “odious beard” that Lady Franklin decried after Rae’s reports of cannibalism among the Franklin crew brought widespread condemnation

.

Rae was still at sea when the controversy was raging. On his return he paid the mandatory visit to Lady Franklin, where the atmosphere was decidedly chilly. She gave vent to her feelings in her journal in what can only be described as a catty attack on the appearance of the explorer that had nothing to do with the subject at hand. She had quite liked Rae before this, but now she wrote, “Dr. Rae has cut off his odious beard, but still looks very hairy & disagreeable.…”

The Admiralty had asked the Hudson’s Bay Company to send a land party down the Great Fish River. Its leader, James Anderson, came back with some scanty remains: part of a snowshoe with “

MR STANLEY

” on its back and a leather backgammon board which Jane remembered putting on board the

Erebus

. There was no doubt now that her husband was dead, but for her that did not end the matter; she simply switched the effort that she had expended trying to save him to a new direction.

She intended to make it absolutely clear to the world that he had been the first to discover the Northwest Passage. Anderson had told her that what was needed was a ship from the north from which sledge parties could reach King William Island. “I am about to make a last effort to solve this mystery before the curtain falls forever over their unburied remains,” she declared.

On January 22, 1856, the government announced that Rae and his men would receive the award of ten thousand pounds for establishing the fate of the lost expedition and that Robert McClure and his crew would receive ten thousand for being the first to negotiate the Northwest Passage. As far as the Admiralty was concerned, that search was ended.

Jane was having none of it. In April she dispatched a voluminous letter—25,000 words—to the Admiralty contesting both awards. But the Admiralty was obdurate, and in spite of appeals to Parliament, the prizes were approved.

Still she did not give up. “Though it is my humble hope and fervent prayer,” she wrote, “that the Government of my country will themselves complete the work they have begun, and not leave it to a weak and helpless woman to attempt the doing that imperfectly which they themselves can do so easily and well, yet, if need be, such is my painful resolve, God helping me.”

That was laying it on pretty thick.

Weak?

She who had climbed mountains in South Africa, America, and Australia?

Helpless?

She who had the ear and the support of the leading figures of the day, including the Prince Consort himself? In June a bevy of famous names was placed on a memorial addressed to Lord Palmerston, pleading for another expedition. One can only conclude that Jane’s appeal to the Admiralty had a whiff of blackmail about it.

Sir Edward Belcher, the least competent of all the Arctic officers during the Franklin search, had foolishly abandoned one of his ships,

Resolute

, which an American whaler later discovered floating about in Davis Strait. Congress bought her for $40,000, had her refitted, and offered her to the British Admiralty as a hands-across-the-sea gift—or perhaps as a piece of naval one-upmanship. Jane’s friend Henry Grinnell wanted the Admiralty to lend the ship to her for a final expedition. At a speech to the Royal Geographical Society by the American ambassador, she primed the chairman, Sir Roderick Murchison, who in turn primed the speaker, who inspired a round of applause when he referred to

Resolute

as “a consecrated ship” with the implication that the Franklin quest was commensurate with that for the Holy Grail.

At the same time, the weak and helpless woman was arranging through friends at the Admiralty for

Resolute

to receive a royal salute. She even arranged for a

Resolute

party for the officers and crew of the consecrated ship—with gifts for all—with the aim, through the careful behind-the-scenes work of others, of having it reserved for her own expedition. She was moving heaven and earth to get her way. Some of her friends in the Commons pursued the idea while another prepared an approving article for the

Illustrated London News

. She herself offered a prize of five hundred pounds to whalers who might investigate a rumour that the missing ships had fallen into the hands of the Inuit.

In addition, she arranged to have Henry Grinnell call a meeting in New York and sent yet another address to the Admiralty urging her right to have

Resolute

. She left nothing to chance, writing the address herself, which she then quoted in a letter of her own to the First Lord with a copy to the Prince Consort. Such was her campaign that even

The Times

argued that the ship should be placed at her disposal. But all her considerable efforts were in vain. The Admiralty demurred.

Still she did not give up. Foreseeing that refusal, Jane had already asked a friend in Aberdeen to examine the screw schooner yacht

Fox

, whose owner had just died. When the report was favourable, she bought the

Fox

for two thousand pounds and put Leopold M’Clintock, an experienced naval man, in charge of her own expedition to explore King William Island, the one corner of the Arctic that had been bypassed.

She gave M’Clintock two objectives: the rescue of possible survivors and the recovery of any records that might confirm the claim that her husband had been the first to discover the Northwest Passage. Time was of the essence; the expedition must sail no later than July 1857, which gave her two short months to organize the expedition, a task that included replacing the vessel’s velvet furnishings and equipping her for the Arctic. To that end she thought nothing of working nights.

She was prepared to spend ten thousand pounds of her dwindling fortune, an outlay that a public subscription reduced by three thousand. M’Clintock and his officers refused to take a penny for the “glorious mission,” which M’Clintock called “a great national duty.” His sailing master, Allen Young, not only served without pay but also contributed five hundred pounds of his own to the public subscription. And when Lady Franklin tried to insist on a deed of indemnity, which would free M’Clintock of all liabilities, he refused it along with the gift of the ship itself, with which she tried to reward him.

Early in July 1857,

Fox

set off on the final mission to solve the ten-year-old Franklin mystery in the only part of the Arctic that had not received any attention but which the persevering Lady Franklin had more than once urged upon the navy.

Fox

was half the size of Franklin’s ships and by no means as sturdy. Until April 1858, it was beset for 250 days in the implacable ice of Melville Bay, being pushed 1,385 miles in the wrong direction—an inauspicious start that delayed the expedition for a year.