Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (49 page)

Read Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power Online

Authors: Steve Coll

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #bought-and-paid-for, #United States, #Political Aspects, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Business, #Industries, #Energy, #Government & Business, #Petroleum Industry and Trade, #Corporate Power - United States, #Infrastructure, #Corporate Power, #Big Business - United States, #Petroleum Industry and Trade - Political Aspects - United States, #Exxon Mobil Corporation, #Exxon Corporation, #Big Business

On August 17, 2006, Ron Royal invited Ambassador Wall to a new office building ExxonMobil had opened in the capital. He noted that Déby had recently restored diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China and that Chinese oil executives were lurking around the capital. The ExxonMobil manager said he feared the American corporation’s presence in the country might be threatened now by Chinese competition. The Chevron tax dispute seemed a symptom of rising troubles and could have knock-on effects on ExxonMobil’s production and sale of Chadian oil. Déby’s regime had indicated, for example, that it might soon try to reopen the convention under which ExxonMobil operated.

Given the “highly tense environment,” Royal told Wall, ExxonMobil would seek a meeting between President Déby and Rex Tillerson.

Déby soon announced that he was throwing Chevron and PETRONAS out of Chad. “A revolution has begun,” Déby announced to a government-organized crowd of a thousand people in the capital. “We are only receiving the crumbs that are called royalties. . . . This is a flagrant injustice.”

This would be a limited sort of revolution, however, he explained. “One company has not failed in its obligations,” the president said. “I’m speaking of ExxonMobil, with whom we will continue to work.”

26

T

wo days later, a young United States senator from Illinois arrived on an American military charter at N’djamena’s airport. Barack Obama, in office less than two years, was on his way back to the United States from travel to Kenya, Somalia, and Chad’s eastern refugee camps. Obama had not been in national office when the World Bank’s experimental project in Chad was born. His interest in the country derived from his interest in the Darfur crisis. Déby’s ambassador in Washington had met with Obama before he traveled and had recommended to Déby that he make time to meet the senator personally when Obama passed through the capital. They scheduled a thirty-minute courtesy call at the airport.

Obama took his seat and thanked Déby for his cooperation with the United States on Darfur and counterterrorism.

Déby in turn thanked Obama for visiting Chad and for his interest in Darfur. The crisis had profoundly affected Chad, he said. Cross-border raids into his country from Sudan continued. The April 13 raid on his capital had been an effort by Sudan “to destabilize the country, bring in a regime favorable to Khartoum, and inflict harm on Sudanese refugees in Chad.”

They talked in some detail about negotiations under way to settle or at least stabilize the conflict in Darfur. Déby rarely let a meeting with an American official go by without emphasizing Chad’s needs and shopping lists. He told Obama that while their countries enjoyed cooperation on counterterrorism, “Chadians still required equipment, and had submitted requests in the past year to U.S. authorities.”

“If a request was submitted, then the Pentagon would be reviewing it,” Obama assured him.

Déby then raised the subject of his threats to throw out Chevron and his problems with the oil companies.

“I am trying to ensure that Chad benefits from oil production,” Déby told Obama. “The Chadian people cannot benefit from the country’s oil as long as Chevron and PETRONAS refuse to pay the taxes they owe. They claim they have a legal basis for not paying income taxes,” but the agreement they signed was not approved by the National Assembly and did not have the force of law.

By deciding to confront the oil companies, Déby continued, he was seeking only to reduce the “economic inequality” between the companies and Chad.

“I can’t speak for the United States or Chevron,” Obama replied. Still, he continued, “two principles need to be considered: that the Chadian people should benefit from the country’s natural resources, and that contracts need to be observed.”

Obama said that Chad “could benefit from foreign investment, but if the rules of the country’s business environment changed, foreign investors would be more hesitant to enter Chad’s economy.” He said he hoped the dispute could be resolved and that Chad “would develop a business environment where contracts were respected.”

27

Déby was accustomed to this sort of lobbying by now. No matter the party membership or political ideology of American visitors, when it came to oil, diplomats and politicians always seemed to emphasize their belief in the rule of law and the sanctity of contracts.

The two men spoke much longer than scheduled. After about ninety minutes they ended their meeting and went outside to hold a press conference, to speak mainly about Darfur. Afterward, Obama flew back to Washington. At the time, Déby’s advisers gave little thought to their president’s encounter with the junior senator from Illinois. “Nobody in Chad really understands the situation in the United States,” recalled Hissène. As for Obama, “Nobody was betting on him at the time.”

Déby flew to Paris to meet with Chevron’s chief executive, David O’Reilly. Their talks stalled, but Déby expressed an interest in meeting with one of Chevron’s international negotiating consultants, Andrew Young, the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Young, on behalf of a consulting firm called GoodWorks International, flew into N’djamena. With his help, Chevron negotiated an agreement that would clarify its tax obligations and those of PETRONAS. As part of the deal, the oil companies agreed to make a onetime payment in 2006. The oil companies paid President Déby’s government a single lump sum of $281 million. A Chevron negotiator privately told the American embassy that the settlement was “not the worst, but not the best.” Chad’s oil would continue to flow; Chevron and ExxonMobil would continue to sell it.

28

Seventeen

“I Pray for Exxon”

D

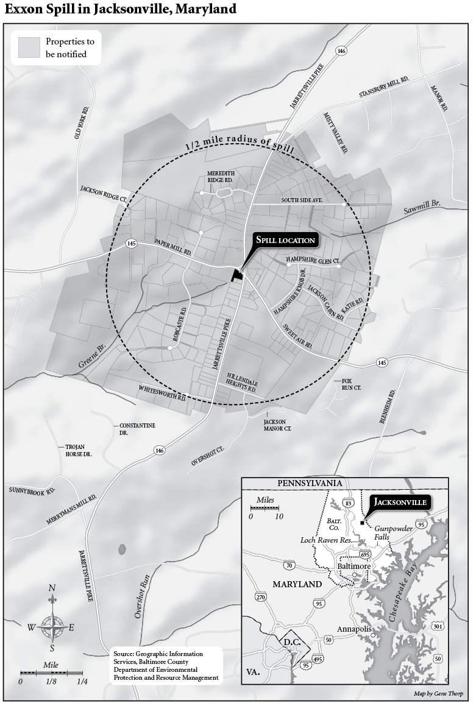

uring the late 1960s, Exxon Corporation erected a gas station near the three-pronged corner of Jarrettsville Pike, Paper Mill Road, and Sweet Air Road in Baltimore County, Maryland. The corner was nestled in thick woods, rolling hills, horse farms, and muddy streams that joined into the Gunpowder River and ran to the Chesapeake Bay. Modest aluminum-sided brick ramblers with long driveways and multiacre lots dotted the region. In the early days after the Exxon gas station opened, new homeowners in the neighborhood topped up their wide-finned Impalas or their 8-cylinder muscle cars while commuting to jobs at restaurants or insurance offices or the industrial sections around Baltimore Harbor. In 1984, Exxon shut its first station in the neighborhood and opened a new one nearby, in the midst of the three-way intersection: Jacksonville Exxon, station number 2-8077, as it was known in the corporation’s vast system of retail gasoline manufacturing and distribution. Suburban sprawl encroached as the years passed, and later, new subdivisions of brick McMansions with granite countertops and chef’s appliances sprang up in the woods. Doctors and city executives refurbished old flagstone farms and transformed them into elegant country estates each worth a million dollars or more. The small ramblers from the 1960s seemed dwarfed by the larger new residences, but all of the area’s homes rose steadily in value as the great American housing bubble inflated. By 2006, Jacksonville Exxon served a growing and economically diverse community in northern Baltimore County: professionals, small-business owners, retirees, and middle-class commuters. All along, for more than three decades, a single family, the Stortos, had operated the Exxon-branded stations and auto repair facilities in Jacksonville; day-to-day management had eventually passed down to a daughter, Andrea Loiero.

1

Altogether, ExxonMobil sold about 14 billion gallons of gasoline to American drivers each year. Andrea Loiero reported to a downstream division of the corporation in Fairfax, Virginia, on the site of the old Mobil headquarters, which oversaw this retail system. There were almost 29,000 ExxonMobil-affiliated gas stations worldwide, about 14,000 of them in the United States. Market researchers conducted public opinion surveys after the merger and discovered that consumers valued and felt loyal to each of the Exxon and Mobil brands, and so they concluded that there was no reason to change any of the names, or to create a combined ExxonMobil brand. More than 8,000 of the gas stations carrying one or the other name were owned and operated by independent distributors who paid ExxonMobil for the right to use the brands and who agreed to abide by the strict rules in franchise contracts. Another 1,000 or so stations were referred to within the corporation as Heritage Mobil stations, branded as Mobil and owned directly by the company. Some were operated entirely by ExxonMobil employees; others were owned by ExxonMobil but operated by an independent dealer under contract. There were also about 2,200 Heritage Exxon stations similarly organized. Jacksonville Exxon was a Heritage station owned by the corporation but managed under contract by the Storto family. It had operated this way since it had opened.

Running a gas station had become steadily more complicated since the 1960s. The typical retail snack and grocery shop under a red Exxon roof now generated as much as or more profit than gasoline sales did. Managing the retail business required expertise in credit cards, customer reward programs, and packaged food supply. Technology and regulation had at the same time transformed the gas station’s physical plant into an intricate system of electronic monitoring systems, interconnected pumping systems, computerized inventory managers, alarms, and console boards. The blinking monitors set up behind the thick safety glass where the cashiers and station managers worked allowed ExxonMobil corporate managers to see from a distance, for example, when a particular dealer like the Stortos needed more gasoline, so that deliveries could be scheduled efficiently. The gas station business had become infused with new technical jargon: What customers referred to casually as the gas pump was now known within ExxonMobil as the M.P.D., or multi-product dispenser. Its digital systems might allow a driver to use a single handle to pump multiple grades of gasoline. A modern gas station’s electronics required continual supervision, to ensure that the systems were operating properly and that gasoline sales were being captured and credited correctly.

The scene at Jacksonville Exxon on the brisk winter morning of January 12, 2006, reflected this new complexity. On one side of the station tarmac that day, a contractor had arrived to fix a submersible sump pump that pulled the gasoline out of the ground and delivered it to the multiproduct dispensers. The contractor was drilling holes in the asphalt. As this work proceeded, around 9:00 a.m., an ExxonMobil tanker truck also arrived to refill the station’s 12,000-gallon underground storage tank.

As the tanker driver directed gasoline down a thick hose into a storage vat, alarms rang out suddenly—they signaled that gasoline was leaking somewhere in the station’s system. All of the multi-product dispenser islands at Jacksonville Exxon shut down automatically, cutting off befuddled customers in midsale.

The tanker-truck driver came inside and spoke to the cashier. “I think I overfilled the regular tank,” he said, referring to the station’s underground storage vat. Spilled gasoline from the tanker hose had set off the station’s gasoline leak alarm system, he suspected.

2

At every stage of its operations—from oil wells in Africa to filling stations in America—ExxonMobil relied on outside contractors to perform much of its technical work. Halliburton and Schlumberger constructed oil and gas wells for ExxonMobil around the world. Companies specializing in offshore oil production leased their ships and crews to the corporation to drill wells in deep ocean water. Similar business practices had become the norm in ExxonMobil’s retail gasoline division. Contractors, not corporate employees, serviced ExxonMobil station managers under fixed-price agreements: They mowed lawns, painted walls, and they also installed and repaired electronic and gasoline storage systems.

When a leak alarm sounded at any Exxon station in the mid-Atlantic region, it automatically alerted a call center in Greensboro, North Carolina, operated by an ExxonMobil contractor called Gilbarco Veeder-Root. The contractor’s technicians in turn telephoned another independent company in Connecticut called I.P.T., which was responsible for dispatching maintenance specialists to Exxon stations. That January morning, in response to the ringing alarm, I.P.T. telephoned Alger Electric, which had a subcontract in the Baltimore area. An Alger truck turned up at the Jacksonville station within two hours of the alarm’s first bell to diagnose and fix the problem, so that the Stortos could begin selling gasoline again.

Alger’s technicians had learned through experience that leak detector alarms at Exxon stations usually did not go off because there was an actual gasoline leak. The detectors were sensitive devices that could be triggered by any number of causes—a paper jam inside the office, a faulty electrical component, or simply because the station was running out of gasoline. “A very big majority” of times that Alger was called to Exxon stations to inspect a leak alarm, it turned out that the alarm had been set off by something other than leaking gasoline, David Schanberger, an Alger manager, said later.

On January 12, the Alger technician first checked for evidence that the gasoline delivery driver had overfilled the storage tank as he had reported to the cashier. There was no evidence of such a spill, however. Then he ran troubleshooting tests on other station equipment. He concluded that a motor in the pumping system was at fault; he unplugged the motor from the leak detector wires, replaced it with a new motor, reconnected it to the leak detector, reset the alarm, and departed. Jacksonville Exxon was back in business and Alger Electric, the repair contractor, was “under the impression . . . that everything was working properly.”

3

R

ussell Bowen had worked for Exxon and then ExxonMobil for thirty-seven years. As a territory manager he worked from his Maryland home and looked after scores of gas stations in his home state, Delaware, the District of Columbia, and northern Virginia. Bowen lived just eleven miles from Jacksonville Exxon. He had known the Storto family for many years. On February 16, 2006—about six weeks after the morning incident with the ringing leak alarm—he was driving back from a corporate meeting in Fairfax when his cell phone rang. It was Andrea Loiero, the Jacksonville Exxon’s manager.

“I’ve got a problem,” she said. “I’m missing some gasoline.”

Bowen asked what she meant. How much was she missing?

About 24,000 gallons, she said. That was a lot—double the capacity of an underground storage tank at the station—and not easy to misplace. Bowen figured that the gasoline was not actually missing physically, but that the problem was probably a faulty meter or a glitch in an inventory computer program. Still, he thought they should be cautious. “Shut everything down,” he told Andrea. “I’ll come on over there.”

4

Bowen had been around the retail gas station business long enough to remember how things were done before all the computers came in. “Back in the day,” as he put it, each gasoline pump had a meter on it called a “totalizer” that kept track of how much gas was dispensed to customers. At the end of each day, the station manager would take a reading off each mechanical pump totalizer and check it against cash register receipts. To complete the inventory check, the manager would grab a dipper stick, go outside, drop it into the underground storage tanks, and measure the level of gasoline, to make sure the level conformed with the totalizer readings and the register receipts. A station manager would expect to lose a few gallons here and there because of small spills around the pump and the like, but otherwise, he would expect the daily totals to be aligned.

It was dark when Russell Bowen arrived at Jacksonville. He first checked the electronic multi-product dispenser totalizer readings; the meters were computerized now but they still counted up the number of gallons of gas pumped that day. Bowen first wanted to be sure that the measuring device was working properly; he bought a gallon of gasoline, pumped it into his own car, and then rechecked the totalizer to see if the sale had registered. It had.

Inside, he found Andrea Loiero in a nervous state. Bowen asked to see her daily inventory records. He saw that Jacksonville Exxon had been posting a “negative variance”—missing gasoline—on the scale of hundreds of gallons each day since early January. Between January 13 and January 31 alone, 14,501 gallons appeared to be missing. Why had it taken her six weeks to notice that so much gasoline seemed to be missing? Had she been failing to undertake her required daily electronic inventory reconciliations? It was just like “doing your checkbook,” Bowen said later. ExxonMobil rules required station managers to report to the corporation if they experienced significant losses of any grade of gasoline. Loiero seemed agitated and confused about what her daily inventory records showed—how the math worked.

“Did any leak alarms go off?” Bowen asked her.

“No.”

The more they talked, the more Andrea Loiero seemed to be “bouncing around,” thinking out loud about the work that had been done by the Alger Electric contractor back in early January.

5

Had that caused the gasoline to go missing somehow?

Bowen called to ensure that another contractor was on his way to Jacksonville to start running new tests on the station’s equipment. He told Andrea to calm down, think through the events of the last six weeks, and write out a chronology that could help them diagnose what had happened.

He returned in the morning and found a new contractor had also arrived with metal tanks full of helium gas. The technician drilled quarter-inch holes in the concrete near the multi-product dispenser to inject gas into the ground, to search for evidence of leaks in the lines or tank walls, through which gasoline might have escaped. About an hour later, he called Bowen: There was a single fluid leak near the station’s big underground storage tanks. It was about the size of the holes that the contractor—who happened also to be from Alger Electric—had been drilling during his sump pump repair project back in January.

The news was catastrophic: In all probability, about 24,000 gallons of toxic gasoline had been leaking into the ground for six weeks in an area where there were houses located within five hundred yards of the Exxon station. Worse still, those homes drew their water supplies from wells drilled on their properties; the county system of piped and treated drinking water did not serve them. Those household wells would be vulnerable to contamination from the gasoline in ways that piped county water would not. Since January, scores of local families and children had been consuming their well water, bathing in it, and cooking with it, unaware that they might be imbibing and dousing themselves with diluted gasoline. How could this have happened? Why didn’t the station’s leak detector alarm bells ring as they were supposed to do?