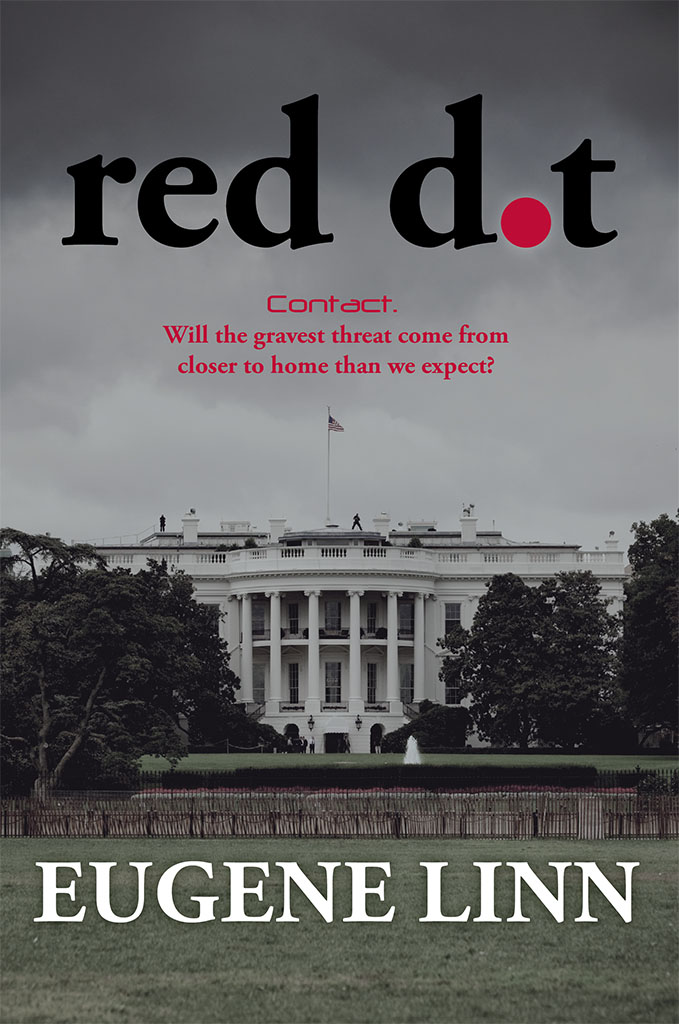

Red Dot: Contact. Will the gravest threat come from closer to home than we expect?

Read Red Dot: Contact. Will the gravest threat come from closer to home than we expect? Online

Authors: Eugene Linn

RED DOT

Contact. Will the gravest threat come from closer to home than we expect?

EUGENE LINN

Copyright © 2015 Eugene Linn

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1517362938

ISBN 13: 9781517362935

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015915242

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

North Charleston, South Carolina

D

EDICATION

To Lilian, my wife.

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

T

HAT

’

S

I

T

T

wo young men

repairing a fence on a wind-swept Kansas pasture spotted something strange almost simultaneously, along the fence line and about 50 yards to their right, down a gentle hill near a stand of cottonwood trees. The sun was low enough on the late summer afternoon to throw shadows from the trees onto the parched, yellowish-green grass a few yards on the other side of the object. Without a word, Bret and his friend Darren tossed their work gloves into their ancient pickup and walked down the barbed wire fence on Bret’s uncle’s farm.

They stopped about halfway to the unusual sight, and stood motionless for a few seconds before Bret said, “What the fuck is that?”

A circle of red about five feet across covered the ground next to a fence post. The color transfixed Bret and Darren. It was red for sure, but not a shade they could identify. It wasn’t a flashy, fire engine color or a pale, pinkish red, or any shade in between that they could name. Whatever color it was, they couldn’t take their eyes off it. The sun reflected off the dot, and it also seemed to glow softly on its own. Grass around the circle bent and wiggled in the wind, but the red surface remained calm, like a translucent shield that reflected and radiated the peculiar red color. The circle seemed perfectly round, as if made by a precise machine. But when they looked closely at the edge, there was no sharp, distinct border.

“Check it out,” said Darren. “See what it feels like.”

“I ain’t touchin’ it. You do it.”

“No.”

They stood silently for a minute or so, alternately staring in amazement and then trying to figure out what they were looking at.

Then Bret said, “You know what, man? I’ll bet maybe it has something to do with that space thing.”

TEN DAYS EARLIER

Three scientists crowded together, watching the dual computer monitors processing information from the 1.5-meter reflector telescope on Mt. Lemon, the largest of three telescopes operating for the Catalina Sky Survey team, based in Tucson. CSS was part of a global network of observatories working in NASA’s Near-Earth Object Search Program to identify far-off asteroids and comets that might threaten to hit Earth—so-called Near Earth Objects. Combined, the five surveys pick out about one thousand NEOs a year. For most newly discovered NEOs, the observatory’s camera took several digitally rendered pictures a few minutes apart. Computer-aided analysis helped check each object’s change of position in the different pictures to determine its direction and distance from Earth. None of the NEOs discovered so far was on course to slam into Earth, though NASA had identified more than two thousand that would pass within 4.6 million miles.

Lai-Wen Cheng, the regular Observer at the facility, sat in his usual place in the middle, with his hand on a mouse. Pudgy and wearing a thick sweater, he filled his well-worn chair with studied familiarity. Lai-Wen was none too happy that the higher-ups saw the need to send officials from CSS in Tucson to oversee this potentially groundbreaking project, and, staking claim to his turf, made sure to leave his coffee cup and pictures of his wife and child in their place on the small, cluttered desk. Tall, lanky programming whiz Dan Simmons stood to Cheng’s right in rumpled clothes he had, as usual, picked out of a pile that morning. Oblivious to any turf war, Dan stared intently at the monitors.

Claire Montague, the CSS Principal Investigator, and head of CSS, leaned on the desk to Lai-Wen’s left, studying the monitors. Cheng was right: He could have handled the project himself. But Claire possessed a rare combination of qualities that marked her for leadership. Ground-breaking academic work as a physics student and impressive decision-making ability in early work at NASA had helped her stand out. But what really set Claire apart was that she was a nerd who enjoyed talking with people. And she was good at it. It was easy to imagine her as a child, meeting adults and other kids and quickly winning them over with friendly and direct enthusiasm. Going

through the normally tough teen years, she’d held onto most of her openness and enthusiasm. What was more: with her honest interest in other people, she didn’t seem to realize she was so accomplished–and good-looking. Claire was sort of like the dark-haired, athletic girl-next-door in the several middle-class and working-class neighborhoods she’d been raised in … if you were a very lucky boy.

Already in charge of CSS, she was due to be promoted soon to a more prestigious and high-visibility NASA post: Deputy Associate Administrator for Strategy and Policy. All-in-all, she was the type of person you would want to confirm and communicate earth-shaking findings.

“That’s it,” she said as the three of them focused on the screens. “It has to be alien.”

For almost three weeks, a small group of scientists at the lab had followed the path of a far-off object with growing excitement and apprehension as it approached the inner solar system from beyond Saturn. First, they routinely plotted its course, as they did for hundreds of comets and asteroids, to determine whether it posed any danger of slamming into Earth. Then in just over a week it had seemed to make a minute course change, and then another. It was relatively routine to determine whether an asteroid or comet was headed toward Earth, but new calculations had been needed when this object seemed to deviate from its expected path. That’s where Dan’s expertise came in. Results indicated that the object—Data23w9, or D9 for short—had made the changes in direction itself. But the staff shrank from making that staggering conclusion.

Now, however, the flickering monitors in the lab revealed an acceleration that

had

to come from D9 itself. Gravitational forces from nearby planets and other bodies obviously could not cause the change.

“Plot the new course,” Claire told Lai-Wen, “and I’ll call Morten.”

“But it’s after midnight,” Dan said.

Claire barely turned toward Dan to acknowledge the stupidity of his statement. How could anyone with such a genius for computer programming make such asinine statements? She swiftly reached for the phone and pressed the button to dial the number for Morten Blackstone. A section chief

in the White House Chief of Staff’s office, Blackstone had been designated as the lab’s point of contact when the possibility arose that D9 was guided by intelligent life. Decision-makers wanted any information to go into political channels first, rather than through government scientists. So Claire had access to Morten twenty-four hours a day, and he’d been given the same access to the President.

After just two rings, Morten answered with only the last traces of sleep-induced grogginess. “What is it, Claire?”

“We got a new reading that shows a purposeful change in velocity.”

“Are you sure it’s directed by alien life?”

Claire was sure, but—surprising herself—she hesitated slightly. She was suddenly aware of the cold, crisp darkness of the night outside the lab in the boondocks of Arizona and, beyond that, the millions of people sleeping, working, playing, and studying in a familiar world that would never be quite the same.

Then she said in her usual, firm voice, “Yes, we’re sure.”

Morten also hesitated for an instant—rare for someone who was full of confidence as a Washington insider, could communicate with the President, and was always quick with a sardonic comment.

“OK,” he said after a second or two. “I’m going to put you on hold while I get President Douthart on the line. It could take a couple minutes, maybe longer. You give him the bare-bones briefing like we discussed, and answer any questions you can.”

“I will,” said Claire, unconsciously straightening up in her chair and for a fleeting moment wishing she had worn something more formal than a Phoenix Suns sweatshirt.

“And this is really important—no one in your lab says anything about this except through the White House.”

For some twelve hours after the matter-of-fact conversation between Claire Montague and President Alfred Douthart, the inner circle at the White House roiled with activity behind the scenes. High-level staff members had already

drawn up extensive contingency plans to deal with political, economic, and other likely problems in response to the lab’s initial reports of a possible alien craft. But the reality of the approaching spaceship threw everyone off track.

As usual, the Situation Room was almost overflowing with people, with President Douthart and a dozen or so Council members, mostly middle-aged white men in suits, crowded around a solid-looking wood table. Their work papers and note pads were scattered in front of them, covering almost the whole table, with a little room for bottled water and cups of coffee or tea. An equal number of earnest-looking, younger support staff members sat in chairs along the walls.

President Douthart famously disdained free-wheeling discussions, but today, talk in the Situation Room swirled for hours in confusion, sometimes addressing three or four topics at once, all of them touching on this approaching object. Would the Chinese cash in their mountains of US dollars? Would the Democratic Congress give the Republican President extra emergency powers? Would terrorists accelerate plans for attacks? What would the markets do?

One prominent topic was the danger of widespread rioting and looting.

“People will say, ‘We’re gonna to die anyway, why worry about the cops?’” insisted Defense Secretary Donner Fitzgerald.

The furrowed brow on his long, thin face seemed to reflect his concern. But his brow was always furrowed, even when he was smiling, and Douthart and his closest advisers had soon noted that in addition to his dour look, Fitzgerald always seemed to emphasize the most dire possibility in any situation, and the most severe course of action. Douthart privately referred to him as “Dr. Doom.”

It was especially worrying, though, that Fitzgerald had a penchant for working behind the scenes to build support for his extreme positions, subtly and skillfully using strong ties with radical media figures to attack the President’s moderate policies in the public eye.