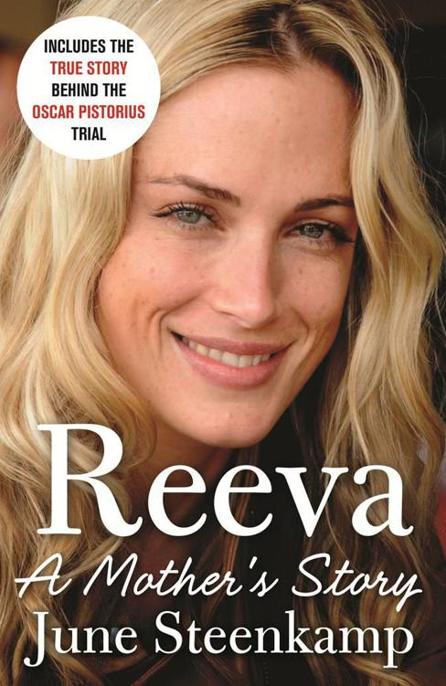

Reeva: A Mother's Story

Read Reeva: A Mother's Story Online

Authors: June Steenkamp

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

COPYRIGHT

Published by Sphere

978-0-7515-5873-9

Copyright © June Steenkamp 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Edited by Sarah Edworthy

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

SPHERE

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

Reeva

Table of Contents

To my angel Reeva

Letter to Reeva, on your eighteenth birthday

19.8.2001

My dearest, darling daughter,

I wish you up to the moon and around the world in wonders or whatever comes to mind that you wish for.

I want to tell you now that you are a full-grown beautiful woman how proud I am of you. You were a gift from God and I have treasured every moment we have shared to date. Now is the time for you to spread your wings and fly in your own direction. I have no worries about this because you are sensible, intelligent and very clued up.

It’s only your heart that may get you in trouble because it’s on your sleeve.

I want to tell you how proud I am of you. You always care for others and you are not self-absorbed. You are dedicated in your future and I see not only the exterior, although it’s beautiful, but inside I see a wealth of qualities reside there.

I love you so much and I just want the best of everything for you.

Happy 18th Birthday Reeva,

Love,

Mom xxx

Letter to June on her fifty-sixth birthday from Reeva

26 September 2003

A whole year has gone by again, reminding us that time waits for no one and that every passing moment is an opportunity to make life that much more sweeter.

I’m happy that I can spend each day with you and grab new opportunities, each time they pass, with you at my side.

I wouldn’t choose anybody else to take this journey with, and nobody else can take your place.

Today is a day to say thanks for being a great person, a beautiful woman, a trusted friend, a devoted mother and most of all – the best you that you can be!

I love you very much.

Enjoy the flowers, pressie, cake and loads of kisses and love – all for you on this day – and tomorrow and the next day and the next…

Your compadre forever

Reeves xxxxx

PS: Dad says ditto for all of the above

Dromedaris Road, Seaview, Port Elizabeth

The beginning of the nightmare.

We are up and about before dawn as usual. Barry sets off for the short drive to the stables at Arlington Racecourse to prepare his horses for their morning exercise. I potter out to greet the overzealous dogs – Boyki and Gypsy the boerboels, Dax and Madonna the Jack Russells and little Moby Dick, Reeva’s dachshund – fighting through playful paws and swishing tails to give them their breakfast. The sun rises just before 6 a.m., promising another balmy summer day. I make tea and start getting myself ready to go to work. At my age I joke my face needs three applications of sand and three of cement. I’m preoccupied with thoughts about the day ahead, about supervising progress at the Barking Spider, a pub we’re building at the Greenbushes Hotel on the Old Cape Road, when my mobile phone rings.

Really? At this time of the morning?

A voice introduces himself as Detective Hilton Botha.

‘Hello, is that June Steenkamp?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you have a daughter, Reeva?’

‘Yes.’

‘There has been a terrible accident.’

‘What kind of accident?’

‘Your daughter has been shot.’

Pause.

‘You’d better tell me RIGHT NOW if she’s dead or alive.’

‘I’m sorry. I’m afraid she has passed on.’

The detective is polite, concerned, saying he wants to inform me before I get in the car and hear it on the radio news. He says he thinks it looks like an ‘open-and-shut’ case. ‘

There were only two people present – your daughter and Oscar with the gun.

’

I’ve heard enough.

I’m hysterical, screaming, sobbing uncontrollably. This cannot be true. The worst thing in the world has happened – it really has – this beautiful, perfect child of mine is dead. We are, we were, mother and daughter with such a strong connection. We are the best of friends, so close we talk about everything. We even have a pact that, if one of us dies, we will let the other know with a sign that we are okay and in a good place.

How can Reeva be dead? I can still hear her chattering away to me last night, telling me that she is arriving at her boyfriend’s house to cook him a romantic Valentine’s Day dinner, that they are planning a quiet evening, that she’s sending money for our cable TV subscription so that we can watch her in the new series of

Tropika Island of Treasure

,

which airs this weekend, and that she loves me. Big kiss!

I visualise the police searching for my number on the contacts list on Reeva’s phone –

Mommy BlackBerry

– while she… I don’t let my mind go further. Imagine answering your phone at seven o’clock in the morning and hearing that your daughter is dead from gunshot wounds. It’s just not real. It’s devastating. Our lodger David hears my anguish and comes to try and help. He says he’ll call my good friends Claire and Sam, and they are here in minutes, not knowing what to do because now I’m almost mute with shock. I manage to phone Barry and tell him he must come home immediately.

Barry drives home from the stables thinking one of the older dogs has died. He misunderstood my hysterical sobs, because I would be upset about the dogs. When he arrives and hears the bitter truth, he goes into a truly terrifying state of shock, trembling violently, and asking over and over again how,

how,

can Reeva, our beautiful baby, be dead. She was our whole life, our

laat lammetjie

, a precious late lamb, the only child we had together, the backbone of our extended family and the glue – let’s be frank – in our relationship. In the few minutes it took the detective to communicate the news, our lives seem to have crumbled like a sandcastle knocked by a freak wave on the beach.

The detective’s words echo in my head:

There were only two people present – your daughter and Oscar with the gun.

What terrible, terrible thing could have happened between two young people to precipitate this? They had known each other for scarcely three months. Reeva, I knew, was excited about and wary of this new relationship in equal measure. When it started, his infatuation was too much, but after a break, she told me she had decided to give her all to the relationship despite nagging doubts about their compatibility. He was hard to please. He could be moody and volatile. But she loved him, and admired him, especially for all he had overcome in life, and how he used that as a power to inspire other people. That was her dream too. She was a caring girl, a nurturer by nature. She wanted to help others. Was it as I had feared when she was eighteen: that her heart had got her into trouble? Did she suffer because her expectations of love were not met?

Barry’s in such a state, and more friends are turning up at the house with condolences. But what can they say? They are shocked. It’s too much for all of us. People from the stables start arriving to support us, the jockeys and members of the racing community whom Barry has known for the last fifty years. Somehow I manage to phone Barry’s younger brother Michael, who is very involved in the church, a lay minister giving occasional sermons and so on. He runs a Christian drug rehabilitation centre outside Cape Town. He’s a lovely kind man and the only one who can calm Barry down. Barry, nearly seventy, is diabetic and not in the best of health. He’s a big, gentle man, but when he gets stressed – and right now he’s in torment, trying to absorb the fact that some guy he doesn’t know has murdered his beloved daughter – he goes from 0 to 300 in five seconds. We need to keep him calm for his health.

I experience all this in a dreamlike, practically comatose state.

Almost immediately the press are outside our little rented house in Seaview; reporters, cars, vans, cameras, cables and mushrooming satellite dishes, all set to camp outside for weeks. Flowers and notes of sympathy start arriving from all over the world. The news of our daughter’s violent death swamps national and international media, with one TV reporter saying it is arguably as big a story as the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990. Princess Charlene of Monaco sends a bouquet. It seems surreal to think that something so cataclysmic has happened to connect a royal palace in Europe with our modest suburban street in South Africa and touched someone living in a world so different from our own that they’re moved to send us flowers and heartfelt condolences. Soon the house is bursting with flowers, their scent overwhelming. Our home, which already had hundreds of photos of Reeva, resembles a shrine. People come to the gate to try and talk to us. They leave messages and food and more flowers.

At the heart of lurid speculation gripping the world’s news sites, the established facts on the Breaking News feed are few: Reeva was shot in a toilet cubicle in the bathroom of the Paralympian athlete’s R4.5 million luxury villa in one of South Africa’s most prestigious gated communities in the early hours of 14 February. Four shots were fired through the locked toilet door. Reeva was hit three times and died of her wounds. A 9mm pistol was seized by police at the scene. The man who shot her through a locked door told his family that he thought an intruder was in his bathroom and that he shot through the door out of fear. This turns out to be the start of a process that lasts through to the end of the trial, where Barry and I pore over every snippet of information, every piece of ‘evidence’ we learn about from the media, to figure out what happened in the hours and minutes leading up to her death. We want to find some comfort from being able to think our daughter died without suffering, without any notion of what was about to happen to her, but everything points us in the opposite direction. We look at everything through the prism of knowing Reeva so well, and imagining all too clearly what she must have gone through.

Barry looks to see if there is any personal message from the man who shot her among the tributes, but there is only a bouquet sent with an impersonal line from his management agency office.

How I get through the rest of the day and night I don’t know. We are lucky to have such amazing friends and family. When I slip into some sort of slumber on that first night after her death, Reeva appears to me in a dream in a long white dress. She looks so beautiful. ‘Mama,’ she says. ‘I hope he doesn’t shoot me again.’ Now in my dreams she only appears as a little girl, and I feed her and nurture her. That first night is the only time she comes to me as her radiant grown-up self.

When I see a picture in the Friday newspaper of the man who has shot her so grievously, I realise I don’t even know him. Yet he is so familiar to the world at large. Newsreaders and reporters express incredulity: how can a sporting hero of his stature, celebrated for his charity work, become a murder suspect? How can a ‘celebrity romance’ end in such a way? It’s hard to match up the story with our understanding of our daughter’s life. To the outside world, the shock is that

he

can be implicated in this violent crime; to us, the shock is that our beloved daughter’s life has been extinguished.