Reinhart's Women (42 page)

Authors: Thomas Berger

The spaghetti sauce proved to be a rich

ragù bolognese,

a far cry from the scarlet acidity of Naples, made from ground beef and pork, bacon, and chicken livers, simmered in beef stock and white wine. Edie had found the recipe in a book.

“Why,” said Reinhart, “this is the best thing of its kind. Did you just happen to have all the ingredients on hand?” It was really a rude question, as he recognized when he had put it. But her transformation from the awkward creature she had hitherto been into this gracious hostess, the accomplished cook, the lovely young woman she was at present, could not be taken as a routine event. Perhaps some of it was due to his altered perception, but if he was drunkenly upgrading her now, he had soberly failed to appreciate her previously.

“Let’s just say that I was planning something, for sometime,” said she.

Reinhart grinned at her over his wine. The Valpolicella was as pretty on the palate as its name was in the ear.

“Edie, all I know of life tells me you cannot always be as sweet as you have thus far been to me, but I’m shamelessly enjoying it at the moment.” He went on in what to him was a logical progression: “I have lived with my daughter all her life, and yet I had no inkling of... what shall I call it? Her darker side? If by ‘darker’ what is meant is not evil but a kind of moral toughness. Winona can be, well, rude of course, but beyond that... not exactly cruel—though I suppose she could be that, too, outside my experience—but ‘forceful’ would probably be an accurate word.”

Edie had stopped eating to listen even more attentively than usual.

He asked: “You know her only to chat in the lobby?”

Now she seemed guileless again. “I’d seen her pictures a lot. You know how it is when you see a celebrity, you feel you know them.”

“It was awfully arrogant of her, though, on the basis of that slight an acquaintance, to want to borrow your car.”

“Oh, I don’t think so!” She took a sip from her glass: There was that about her mouth which suggested the curve of a stringed musical instrument.

She went behind the counter.

After a while Reinhart said: “You, Miss Mulhouse, are making a spinach salad with a warm dressing of bacon and vinegar.” He saw that the minced bacon had previously been rendered of its fat; the skillet was now being reheated on the stove behind her as Edie thin-sliced some plump white mushrooms.

When she took away the dinner plates and served the salad, he said: “The mushrooms are definitely an asset. I have previously known only the purist version: all green, except for the flecks of bacon, though there are those, I believe, who sprinkle on chopped hard-boiled egg, but that is almost entirely an aesthetic effect.” He winked at her. “Forgive me for the shop talk.”

“Don’t stop,” said Edie. “I really like to hear it.”

“Judging from this meal, in composition and execution, you know quite a bit about food already. It’s the kind of simplicity that comes only with gastronomical sophistication. For some reason you were deceiving me, with your talk of living on hot dogs and hamburgers.”

Edie stared at him. “I swear that I just got all these things out of a book.”

“Nothing wrong with that. It’s exactly how I learned to cook seriously.”

“But this is the first time for me,” she said, with a mixture of shyness and something else, perhaps defiance: as if she were talking of a sexual experience. “I’ve never really cooked anything before, except maybe a fried egg.”

Reinhart nodded sagely. “You see how easy it is.”

“Is it really O.K.?” asked Edie. “Or are you just saying that?” She proceeded to give him an intimate feeling by chiding: “You are always being too easy on me.”

“Winona says the same thing.” Reinhart brought his fingertips together. “Can I help it if I like girls?” Now Edie sighed cryptically. “Look,” said he, “the Center Café in Brockville? I was out there again today. It’s become an obsession with me to think of acquiring it somehow. It’s a fantasy and will probably never come to reality, but I’ve started anyway to assemble a staff of kindred souls. Would you want to be part of it in some fashion?”

“Me?” Edie drew back on the stool. She seemed genuinely startled.

Reinhart touched the Formica counter with his forefinger. “You’re a cashier by trade, are you not? Am I wrong in thinking that if you could practice your profession at a bowling alley, you could do it at a restaurant, where at best the traffic would be lighter? ...Mind you, this is all theoretical at the moment. I am not even considering how we could earn a profit. Marge has been losing money.”

Edie received this information inscrutably and then went around to the kitchen, opened the freezer compartment of the refrigerator, and removed an ice-cube tray. She looked into it and winced, agitated it slightly in her hand, and winced again.

“Something didn’t jell?” Reinhart asked.

“Pear sherbet. I’m afraid I flopped at that.”

“No, you didn’t. It just hasn’t had time to freeze. It takes a while.” That was the very dessert he had made for the uneaten brunch to which Grace Greenwood had been invited.

“Would you like to have coffee in the living room?”

He was not unhappy to be relieved from sitting on the stool, which was a jolly perch at the outset, but even when younger, with his length of body, he liked at certain points during a meal to lean against the back of a chair.

“I’ll pass up the coffee, though, if you don’t mind. I have acquired the kind of equilibrium between food and drink that caffeine might unbalance.” He went in to the couch. “Why don’t you sit down and tell me about yourself?”

Edie took off her apron. In the living room she chose a chair some distance from him. She looked at him and said levelly: “I’m not gay.”

Reinhart had not been prepared for this statement. Of an unusually generous supply of possible reactions he chose in effect to shrug it off. “Neither am I.” He had brought his glass of wine along, and now he drank some.

Edie said almost fiercely: “I’m not criticizing anyone who is.”

“I know you’re not,” said Reinhart. He raised his glass to her, but lowered it without drinking. “I must tell you, Edie, that I suspect you do everything well, but you pretend to be defenseless. You must be aware that that’s an old-fashioned style. It’s the one I have always preferred, though having had not only the other kind of mother but also the other kind of wife.”

“Sometimes,” Edie said, “it seems at first you are making fun of me, but then I realize you’re not.”

“That’s right. I’m not. I don’t ever make fun of anybody.” He put his glass down and got to his feet. “I think I’ll leave now, though it is awfully rude to eat and run. But I’ll tell you why I think it’s necessary: on the one hand, I think I desire you, but on the other I dislike the

idea

of lasciviousness in a man of my age—if what I feel is that. I have just been separated from a daughter who is only a year older than you. Maybe what I feel is really a simple longing to be in the presence of a young woman to whom I’m closely attached, and since you’re not a relative by blood, I crave some other kind of intimacy.”

Edie remained seated and looked up at him with deep blue eyes, “Are those good reasons for leaving?”

“Then how about cowardice?” But she laughed at him. “All right, then, I’ll just take a nightcap, but first I have to go to my own apartment for a moment. I have to make a phone call. Business....” He put his hand out, and she gave him hers. “Don’t go anywhere.”

“Not me,” said Edie.

He took the stairway down to the fourth floor. Inside the apartment he found he had to look up the number in the public book: Winona had taken the personal directory from the drawer in the telephone table. He wished she had also taken that etching full of hairy lines.

“Grace, Carl Reinhart.”

“Aha.”

“May I speak to my daughter?”

“She’s not here at the moment, Carl.”

“Not there?”

“That’s right,” Grace said tartly. “She went to the movies.”

Reinhart looked down into the living room, but the light was too dim to see the little clock above the liquor cabinet. “She’s out alone this time of night?”

Grace snorted. “She’s with Ray!”

“Ray?”

“My son. He’s in from California for spring vacation.”

Reinhart had never heard of this person before, but he felt that courtesy required him to fake it. “Oh, yes,

Ray.

He’s in the last year of college, isn’t he?”

“Last year of law school!” crowed Grace. Her voice had very clearly taken on an unprecedented tone of affection. This too was new to Reinhart. He had never heard her use it with reference to Winona, but there are all forms of human emotion, and he himself had certainly experienced many of them.

He said sincerely: “I’d like to meet him.”

“You would?” Grace asked, incredulous for a moment, and then she recovered: “I want you to! Which night’s good for dinner? It’s on me this time. But you pick the restaurant. You’re the expert. Make it fancy. We’ve got all kinds of celebrating to do. Did you know that tomorrow I become president of Epicon?”

Reinhart congratulated her. “And I have a new idea I want to talk to you about in the area of food,” said he. “How about Tuesday night for dinner?”

“I’d better check with Ray first. He’s seeing my ex, his father, one night this week. ... Good to talk with you, Carl. When should Winnie return the call, tonight still or tomorrow?”

“I’ll call her tomorrow,” said Reinhart. “It’s nothing crucial.”

“Sleep tight,” said Grace, in what would appear to be a certain affection for

him.

Well, he had never thought her the world’s worst.

As he rode the elevator up to Edie’s floor Reinhart understood that Winona’s absence at this moment was another piece of the good luck he had been enjoying lately. How fatuous had been the impulse to ask her whether she could permit him to have a girl friend younger than herself. Of course she would have refused! Winona was a notorious prig. Who would want any other kind of daughter?

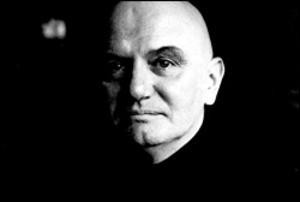

A Biography of Thomas Berger

Thomas Louis Berger (1924–2014) was an American novelist best known for his picaresque classic,

Little Big Man

(1964). His other works include

Arthur Rex

(1978),

Neighbors

(1980), and

The Feud

(1983), which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Berger was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of Thomas Charles, a public school business manager, and Mildred (née Bubbe) Berger. Berger grew up in the town of Lockland, Ohio, and one of his first jobs was working at a branch of the public library while in high school. After a brief period in college, Berger enlisted in the army in 1943 and served in Europe during World War II. His experiences with a medical unit in the American occupation zone of postwar Berlin inspired his first novel,

Crazy in Berlin

(1958). This novel introduced protagonist Carlo Reinhart, who would appear in several more novels.

In 1946, Berger reentered college at the University of Cincinnati, earning a bachelor’s degree two years later. In 1948, he moved to New York City and was hired as librarian of the Rand School of Social Science. While enrolled in a writer's workshop at the nearby New School for Social Research, Berger met artist Jeanne Redpath; they married in 1950. He subsequently entered Columbia University as a graduate student in English literature, but left the program after a year and a half without taking a degree. He next worked at the

New York Times Index

; at

Popular Science Monthly

as an associate editor; and, for a decade, as a freelance copy editor for book publishers.

Following the success of Rinehart in Love (1962), Berger was named a Dial Fellow. In 1965, he received the Western Heritage Award and the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Award of the National Institute of Arts and Letters for

Little Big Man

(1964), the success of which allowed him to write full time. In 1970,

Little Big Man

was made into an acclaimed film, directed by Arthur Penn and starring Dustin Hoffman and Faye Dunaway.

Following his job as

Esquire

’s film critic from 1972 to 1973, Berger became a writer in residence at the University of Kansas in 1974. One year later, he became a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Southampton College, and went on to lecture at Yale University and the University of California, Davis.

Berger’s work continued to appear on the big screen. His novel

Neighbors

(1980) was adapted for a 1981 film starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd. In 1984, his novel

The Feud

(1983) was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize; in 1988, it too was made into a movie. His thriller

Meeting Evil

(1992) was adapted as a 2012 film starring Samuel L. Jackson and Luke Wilson.

In 1999, Berger published

The Return of Little Big Man

, a sequel to his literary classic. His most recent novel,

Adventures of the Artificial Woman

, was published in 2004.

Berger lived in New York’s Hudson Valley.

In 1966, two years after he wrote

Little Big Man

, Berger stands at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the site of Custer’s last stand in 1876. This was Berger’s first visit to the famous battlefield.