Reinventing Emma (3 page)

Authors: Emma Gee

Chapter 2

A Taste of the Future

In 2003, three years into my occupational therapy degree, I decided to take myself off to Tanzania for a few months. Looking back, I can't believe I did this. I'd led a sheltered life and hadn't even done the Europe trip like most of my friends. Mum was very hesitant to let me go and insisted I wear a wedding ring to ward off any admirers. It didn't work. I had 18 marriage proposals in three months! I volunteered as an assistant at the Tuppendane Centre in Maji Ya Chai village, Arusha, where my job was to help care for and educate 70 street children.

Em takes a break from her studies, caring for 70 street children in Arusha, Tanzania 2003.

Tanzania certainly provided the challenge I was looking for. There was no electricity or water, and my accommodation was a rat-infested concrete blockhouse. The guard of the centre would lock me in at night to keep me safe, but inside was worse than out. I was trapped inside with the furry creatures, and plugging the gaps in the walls with my camping socks didn't deter them. All night rats would squeal and run around the room and clamber up and down my mosquito net as I pelted them with boxes of medication, the only weapons I had. It was a hideously claustrophobic experience that I was to relive in a surreal way years later when I woke up in hospital trapped inside my own body.

Being the only

mzungu

(white person) in the small village, I stood out, something I'm used to now but wasn't then. On my daily walks I was joined by a stream of African children, my blonde hair was patted for good luck and everyone would say, “Good morning to you!” It was the only English phrase they knew and they used it whether it was morning, afternoon or night.

Living in a third world culture was a huge eye-opener. âSick days' didn't exist, even though many villagers were constantly suffering from malaria. Complaining, I soon realised, was just not part of their culture. One day I had lunch at a villager's house and was saddened to see his two-year-old son with a severe eye infection. He was too young to complain but even if he was able to I'm sure he would not have mentioned his discomfort. His family couldn't afford medication, and the only way I could help was to buy him eye drops. Now, when I constantly suffer eye infections, I can't imagine letting them go untreated.

Seeing the lives of the children in Africa was like being on another planet. I couldn't believe how sheltered my life had been. Typically I'd pass children on my walk through the village carrying buckets of water on their heads. Four-year-olds would be put in charge of ten cattle and a donkey, with only a stick to control them. Children seemed almost expendable; mothers would plead with me to exchange their newborns for a few dollars so they could buy a bag of rice.

A disabled child was a source of shame. Once I saw an African lady carrying âdizzies' (bananas) on her head, and carrying a newborn baby on her back covered by a sarong. It was hot and I thought she was protecting him from the heat. Then a local villager approached her and they exchanged words about the new baby. The mother lifted the shield, I assumed to show off her new baby, but both mother and onlooker pointed and laughed at the baby, who had Down Syndrome. He was clearly regarded as a reject.

Another cultural learning curve was when I witnessed one of the 70 orphans in my care, an eight-year-old girl, being sexually abused by a nine-year-old boy. When I told the visiting social worker about it, assuming he'd be shocked and take some kind of action, he just said, “Emma, they are street children, and Amelia is retarded!”

I was outraged at his words. “Well surely that is even more reason to act now!” He didn't seem fazed by my anger and went on crunching on his maize. I couldn't believe he could swallow it.

At the Tuppendane Centre I was quickly thrown in the deep end. A few days after I arrived the head of the centre disappeared with the large sum of money I'd paid to the volunteer organisation. Then the sole nurse left to give birth, leaving me in charge of the health and education of all of the children. Overnight I became nurse, teacher and mother to a wild bunch of non-English-speaking orphans, ranging from toddlers to young adults. With the extra challenge of no water or electricity, my twin sister's motto of âface your fears' was truly put to the test.

As bad as things were, I was surrounded by uncomplaining Africans, so I really had to rise to the occasion. Before I could get anything done I needed to be able to communicate with the children, so I set about learning some basic Swahili. They had no shoes, so I bought a hundred pairs of

malopas,

the African version of thongs. I also purchased rat-proof barrels in which to keep food, and contacted a toothbrush company in England and asked them to sponsor the centre by sending toothbrushes. Most of the kids had fungal infections on their scalps, so I also launched a haircutting and treatment program.

Living within a very vulnerable community was a huge personal challenge. My experience there unmasked qualities that I didn't know I had. Away from my âtwinness', my dormant stronger attributes, qualities that I had thought only Bec had, revealed themselves. Travelling alone, I was forced to be more direct, strong-minded and assertive. I also saw firsthand the importance of many human skills like communication that I'd taken for granted. When living in Africa I had to rely heavily on facial expressions and body language to work out what was going on around me. In a strange way it was a foretaste of what was to come. Not being able to speak the language made me feel isolated and helpless, like I would later feel when I lost the power of speech.

In Africa I really saw and understood what discrimination means, something I now experience daily because of my disability. The frustratingly slow-paced culture taught me patience, which I've certainly needed through my long months and years of rehabilitation. It was also a real-life lesson in taking the time to understand where the other person was coming from, rather than just acting like the âexpert'. Later, when I became a patient myself, I learnt to value therapists and others who used this empathetic approach.

I only spent three months in Africa but they were intense. What had been seemingly important in the western world became irrelevant. I learnt that when faced with any obstacle and out of your comfort zone, you can still have control over how you choose to deal with things. Their âlive one minute at a time' approach made me see how much I had been focused on acquiring certain possessions, achievements and status before I could be content. The African people had little but it didn't seem to affect their happiness in the present moment.

Chapter 3

Signs of Something Wrong

After those extraordinary three months in Africa I came back keener than ever to finish university and start a career where I could help people and make a difference. I graduated from La Trobe University with a Bachelor of Occupational Therapy (OT). As an OT my role was to get people who had an injury back to engaging in everyday activities. My first job was as a locum at Caulfield General Medical Centre (CGMC), the same place I was to end up as a patient a few years later.

Em graduates with a Bachelor of Occupational Therapy, La Trobe University 2003.

Right from the start I loved my job. Through university I'd worked in a pharmacy and counted the hours and the dollars. As an OT, I was doing something I was passionate about, so being paid seemed like a bonus.

After Caulfield I began working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital where as a new graduate I was rotated through different areas. I worked in rheumatology, back care, pain management, hand therapy and neurology. In back care the caseload was fairly routine work, mainly WorkCover patients. But in neurology the work was much more varied and interesting. I worked with people in their own homes, for example, helping someone with multiple sclerosis relearn how to shower or a hairdresser who had had a stroke relearn how to cut hair. The gains were obvious and rewarding and I enjoyed the holistic nature of the work, being with people in their own environments. I quickly grew to love this area of OT.

By February 2005, though, I was ready for a holiday. I hadn't had one since Africa 18 months earlier, and I felt I needed reviving before giving the new job my best shot. I'd just broken up with my long-term boyfriend and was ready for some quality girl time. With three of my closest friends, Al, Fi and Kiri, I set off to spend two weeks in Sabah, Borneo. It was an active holiday; we climbed mountains, snorkelled off the islands, saw the orang-utans and explored the local markets, enjoying the Malay culture and amazing food.

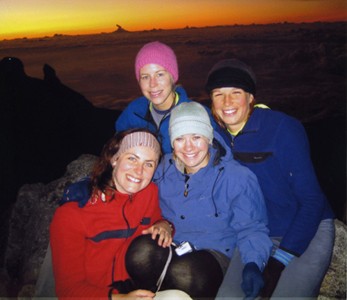

Reaching the peak of Mt Kinabalu, Malaysia at sunrise (Fi, Kiri, Em and Al). This climb in April 2005 precipitated Em's AVM bleed.

It was in Malaysia that I began to notice some strange changes in my body. Because we were in the tropics we had to take anti-malarials and I had chosen doxycycline, which has a side effect of light sensitivity and nausea. As well as those symptoms I began to experience back pain and found I was a bit clumsy, but I put it down to the the drug and perhaps just being too relaxed on holiday.

The big thing we all wanted to do on this trip was to climb Mt Kinabalu. It was over 4000 metres high but in the Lonely Planet guide they said the climb was easy and that “Grandmas could do it,” so I wasn't worried. I was fit and I had packed knee tape as a precaution because my knees had suffered in the past as a result of netball. We ascended the mountain in silence, like a human snake. I was ahead the whole way, followed by my friends and rounding us up was our porter Ami. All you could hear were our increasing gasps for air. Step by step. It seemed endless. We were told that as the altitude increased, the foliage would change, but I didn't expect bodily changes as well.

The plan was to reach the top of the mountain for sunrise. It was pitch dark. We'd walk ten metres and need to stop to catch our breath.

Grandmas couldn't do this!

I was struggling and we weren't anywhere near the top. I had an excruciating, piercing headache and my left side was painfully freezing. I didn't say anything, partly because I felt paralysed with the pain, but also because I assumed everyone else was feeling the same.

The exhilaration of reaching the top and looking down at the clouds justified the tiredness and pain. Sharing that moment with friends had made the struggle worthwhile. Then of course the exhilaration turned to dread. The saying, “What comes up, must come down,” was true. The human snake reversed, and we set about crab-stepping down the mountain. The novice climbers we passed asked, “How was it?” and we replied, “Fine.” On the way up we'd asked the same question and got the same white lie reply. There was no point in telling them how hard it was. They had to experience it to truly understand.

After the big climb we had three days of sleeping, snorkelling, diving and eating to get over the ordeal, but my body didn't feel right. I was ultra-sensitive to light, my skin blistering easily, so I decided to go off the doxycycline early. The risk of malaria seemed preferable to these horrible side effects. I was also clumsier than usual but I put that down to being an after effect of the climb. The plane trip home was agony. My neck and back were excruciatingly painful. Unable to sit, I lay on the airport floor and spent the entire flight walking up and down the aisles, while the other girls slept.

The day after my return I started work. In spite of the strange symptoms I'd returned with, I was otherwise brown, rested, refuelled and ready to put lots of energy into my role as a neurological therapist. I didn't realise that it was my own brain that was about to become the centre of attention.