Authors: Charlotte Gray

Reluctant Genius (22 page)

Long engagements were not unusual in this period, but by November 1876, Mabel and Alec had been engaged for a year, and there was no marriage ceremony in sight. The American prototype of the telephone still needed further work. With the American patent secured, the way was clear for Alec to apply for a British patent, from which, if a manufacturer took it up, the inventor might earn a respectable income. But the application involved writing up specifications, and Alec hated paperwork. “Even your love,” he confessed to Mabel, “fails to overcome the procrastinating spirit that leads me to put off to the future the accomplishments of every difficult task.” Mabel could not resist comparing the work habits of her father and her fiancé. “Why cannot you work like Papa,” she asked Alec, “who goes on steadily day by day doing as much as he can and only

so

much, so never getting tired and having to give up?” In November, Gardiner Hubbard tried a different tack in his efforts to chivy Alec into action. Recently appointed chairman of a special federal commission to look into railroad mail transportation, he swept Mabel off on a trip across the American continent. Each day, Mabel sat by the train window, recording the passing scene in letters to Alec. She described Chicago’s “disagreeable, unfinished look,” the “dreary yellow Prairie stretching way to the barren bluffs,” and the number of houses in Salt Lake City occupied by the wives of Mormon leader Brigham Young. Gardiner’s tactic worked: a letter from Alec reached Mabel in Colorado, reporting that the specifications for the British patent had finally been sent to London. At the same time, Alec finally completed the report for the Philadelphia Exhibition Bureau of Awards, so that his two gold medals could be sent to him.

Alec continued to remodel both the speaking and the hearing equipment of his telephone and to manipulate different kinds of materials to improve clarity. In October, he decided to try out a two-way conversation, and sent Tom Watson plus both transmission and receiving devices off to a factory in Cambridge. He remained in Boston, in the Exeter Place boardinghouse where both he and Tom were now living, waiting for Tom to communicate. Within hours, the two men were enjoying the first two-way long-distance conversation. When Watson got back to their boardinghouse in the early hours of the morning, he and Alec were so excited that they took off their jackets, started whooping, and performed the Mohawk war dance together. The following morning, an indignant landlady told Watson, “I don’t know what you fellows are doing up in that attic but if you don’t stop making so much noise nights and keeping my lodgers awake, you’ll have to quit them rooms.”

The local press soon started to take note of Alec Bell’s activities. When he and Tom Watson managed an easy two-way conversation between Boston and Salem, eighteen miles away, on November 27, the

Boston Post

carried an item about it. The reporter noted incredulously, “Professor Bell doubts not that he will ultimately be able to chat pleasantly with friends in Europe while sitting comfortably in his Boston home.” A more substantial article appeared in

Scientific American,

giving Alec the credibility he needed with manufacturers and fellow inventors. Soon he and Tom Watson had done sufficient work on their prototype telephone to justify applying for a new patent in Washington. With uncharacteristic focus, Alec managed to complete the application in early January.

His new application covered refinements to the transmitter and receiver, which were housed in a wooden box, and used a steel horseshoe-shaped permanent magnet with shorter coils of a finer wire than the earlier designs had. Issued on January 30, 1877, Patent No. 186,787 was the second of the two fundamental telephone patents that secured Alecs ownership of his invention. At this stage, the Bell telephone looked like a box camera, with a single lenslike opening that served as both mouthpiece and earpiece. Callers spoke into the wooden box, then pressed their ears to it to listen to the response. But Alec and Tom were already working on the next generation of their prototype: the wall-mounted “butterstamp telephone.” This featured a handheld receiver-transmitter that the caller could move between ear and mouth. Its diaphragm was enclosed in a flat disk atop a wooden handle, resembling the kitchen implement that was used to stamp butter pats, through which the wire from the battery was threaded.

What with research, teaching commitments, and an ever-increasing volume of correspondence, Alec was overwhelmed by demands on his time. It seemed as though

everybody

wanted to purchase a telephone or to invite Alec to speak or to offer their own theories on how telephones worked. One man turned up at Bell’s door insisting that the telephone was obsolete because two prominent New Yorkers were already beaming their voices directly into his head. If Dr. Bell wanted to find out how this worked, the stranger insisted, he should take off the top of his skull and study the mechanism. “I knew,” Tom Watson recorded, “I was dealing with a crazy man.”

Each time Mabel visited Alec’s rooms in Exeter Place, she was more appalled at the clutter: ramparts of books barricading his bed; paperwork piled so high on his desk that it was impossible to find a blank sheet on which to write, let alone a pen. Eighty-three letters arrived within a four-day period in early March. In April, despite Mabel’s efforts to keep on top of the correspondence, there was a stack of sixty letters awaiting replies. And Alec was still dissatisfied with his telephone prototype. Applications for telephones were arriving from entrepreneurs in cities such as Detroit, Akron, and Syracuse, but Gardiner Hubbard (who handled them) was reluctant to manufacture and supply copies of the prototype until it was completely reliable.

As the pressure mounted on Alec, his headaches returned. He cleared a space on his desk and scribbled a miserable note to his beloved.

When will this thing be finished? I am sick and tired of the multiple nature of my work, and the little profit that arises from it. Other men work their five or six hours a day, and have their thousands a year, while I slave from morning to night and night to morning and accomplish nothing but to wear myself out. I expect that the money will come in just in time for me to leave it to you in my will! Oh! How I long for a nice little home of my own—and a nice little wife in it, and some time to rest. Don’t scold me dear … I am sad at heart, and keep my feelings bottled up like wine in a wine cellar— only they don’t grow any better by keeping!

But Alec never lost faith in his invention. Two days later, in another note to Mabel, he described to her how, very soon, people would be able to “order everything they want from the stores without leaving home, and chat comfortably with each other … over some bit of gossip.” Then, he assured her, “Every person will desire to put money in our pockets by having telephones.” Then, he and Mabel could afford to get married.

Alec, like his father before him, understood that scientific demonstrations still provided some of the most popular entertainments available. In the pre-movie era, members of the expanding, increasingly well-educated middle class were happy to spend a few dollars to improve their knowledge with a magic lantern show on the “Wonders of the World” or a talk on Darwin’s theory of evolution. Often the “science” was pretty suspect: for years, for example, the famous Fox sisters, Maggie, Kate, and Leah, from Rochester, New York, had been holding audiences in thrall with demonstrations of table-tapping and spirit-rapping. So Alec wasn’t surprised when requests for demonstrations started arriving at Exeter Place. Mabel’s mother was horrified at the notion of her future son-in-law, a university professor, joining a throng of clairvoyants, hypnotists, and levitationists on the stages of small towns across America and Canada. “I heartily disapprove of Alec’s giving telephonic concerts. I think it undignified, unscientific, mercenary—claptrap, humbug, Barnum, etc.” But Alec, who only months earlier was decrying medals as “vulgar,” now realized that public lectures would at least replenish his wallet.

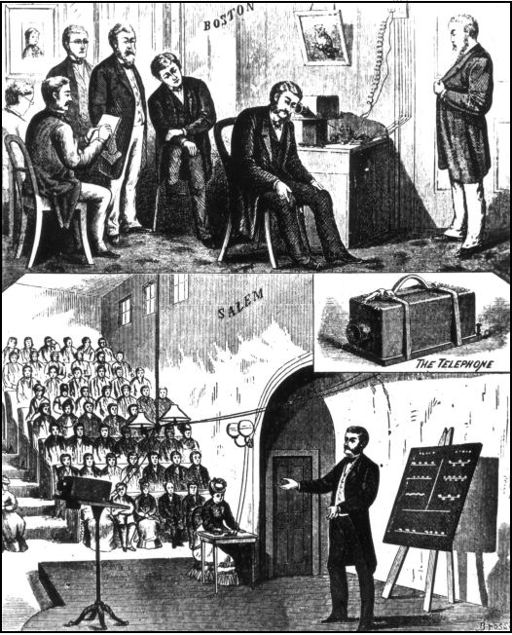

Alec’s theatrical talents drew large crowds to demonstrations of his invention.

On February 11, Mabel traveled to Salem and joined Mrs. Sanders in the Lyceum Hall there to see Alec give a telephone lecture and demonstration. This was the first time she had seen Alec perform in public; knowing how high-strung he was, and that he had been stricken with a migraine a few days earlier, she was almost paralyzed with nerves herself. The lecture was scheduled to begin at half past seven, but by ten to eight Alec had not appeared and the overflow crowd was getting restless. The stuffy wooden hall was filled with the fug of damp woolen overcoats, oil lamps, and the wood-burning stove. Mabel sat in the second row, smiling graciously but twisting her gloves between hands clammy with nerves. She was convinced something dreadful had happened. Mrs. Sanders nudged her, and mouthed a dismissive comment that she had heard from someone in the crowd: “Oh! Telephony and blue glass [for which there was then a fashion] will both go the same way!” A rising cacophony of stamping and catcalls began.

Finally, to Mabel’s intense relief, Alec appeared on the stage and the audience broke into thunderous applause. Always at his best when teaching, he spoke fluently and easily, without notes. He described to his audience not only how his invention worked but also its purpose. It was not just an electric toy that could link two speakers, he insisted. He envisioned a central office system that could connect telephones in various locations with a “switch.” His listeners shook their heads skeptically as he went on to suggest that, within a few years, people in different cities would be able to call each other up and have a chat.

Then it was time for Tom Watson, sitting in the laboratory eighteen miles away in Boston’s Exeter Place, to speak down the line. Mabel described the excitement to her mother: “Alec requested the people to keep perfect silence and the room became so still that I felt it and hardly dared to breathe. The voice was heard to the farthest end of the hall, and you ought to have seen how they laughed and cheered.” The sound of Watson’s greeting (“Hoy! Hoy!”: the salutation he and Alec always used), renditions of “Auld Lang Syne,” “Yankee Doodle,” and “The Last Rose of Summer,” and remarks about an engineers’ strike on a local railroad were clearly audible. “My singing was always a hit,” Tom later wrote. “The telephone obscured its defects and gave it a mystic quality. I was always encored!” Various prominent Salem citizens then spoke to Tom. Mabel knew by the crowd’s reaction that the demonstration had been a greater success than Alec had even dared hope; she herself, of course, had been unable to hear Tom’s disembodied voice.

A

Boston Globe

reporter pronounced the evening “an unqualified success.” The

Providence Star’s

reporter gushed over the inventor, “a tall, well-formed gentleman in graceful evening suit, with jet-black hair, side-whiskers and mustache.” The reporter was not the only person smitten by the star. Mabel reported that “some ladies even spoke into the telephone. Alec could not get rid of them.”

Newspapers far beyond Salem picked up the story of Alec’s lecture. The

New York Daily Graphic

carried an illustrated account, along with a full explanation of how the telephone worked. A month later, the

Athenaeum

of London picked up the story, and in April, Paris’s

La Nature

published an article entitled “Le télégraphe parlant: téléphone de M. A. Graham Bell.” After seven lean years, Alec, now thirty, could finally dare to imagine a prosperous future. He decided to charge $200 to any organization that wanted to sponsor one of his lectures. As soon as he had some money in his pocket, he commissioned a special gift for Mabel: a tiny silver model of a telephone, which cost him $85. Tom Watson was shocked at this “bit of extravagance.”

Alec’s lectures up and down the eastern seaboard, including dates in Boston and Springfield, were usually a hit. Alec had inherited his father’s and grandfather’s stage presence, and he would stride confidently onto the platform, cutting an impressive figure in (thanks to Mabel’s insistence) a well-brushed coat, his hair neatly trimmed. He captivated his audiences with his ability to translate scientific language into simple English before enthralling them with the sound of a voice transmitted from several miles away. In March 1877, more than two thousand people braved a snowstorm in Providence to see a demonstration of the telephone by its inventor. “After the lecture,” Alec wrote to Mabel, “I was besieged by ’Autograph Hunters’!!!”

Alongside the widespread enthusiasm, however, there was a sense that the telephone had sinister implications. Alec’s act was certainly good entertainment. As the

Providence Star

editorialized, “the sensation felt in talking through eighteen miles … leaves the spiritual séance away back in primeval darkness.” But hearing voices when no one was present was historically considered evidence of insanity, and few people could understand how electricity, whatever its other miraculous qualities, could produce or convey a human voice. That, after all, was a gift from God. The

Providence Press

suggested that “[i]t is difficult to really resist the notion that the powers of darkness are in league with it.” The

Boston Advertiser

stated, “The weirdness and novelty were something never before felt in Boston.” The

New York Herald

found the telephone “almost supernatural.”