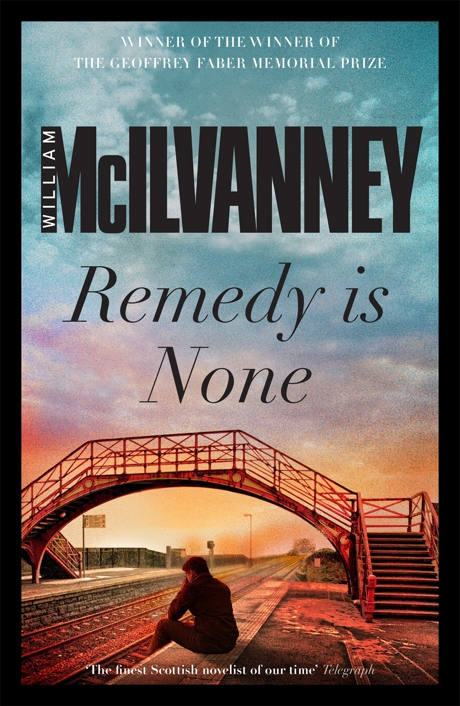

Remedy is None

Authors: William McIlvanney

REMEDY IS NONE

WILLIAM McILVANNEY

First published 1966 by Eyre & Spottiswoode

This digital edition first published in 2014 by Canongate Books, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

© William McIlvanney 1966

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78211 192 4

To my Mother

Contents

Since for the Death remeid is none,

Best is that we for Death dispone,

After our death that live may we:

Timor Mortis conturbat me

William Dunbar (1465 – ?1520)

Part One

Chapter 1

‘

OF COURSE, GENTLEMEN, AT THE BEGINNING OF THE

play you will remember (those of us who have read the text) that Romeo is in love not with Juliet, but with someone called Rosaline. In fact, it might be truer to say that at this point his love is not so much directed at any specific person as at woman in general. The American writer William Saroyan has a short story entitled

Seventeen

which effectively conveys the state of mind we may assume him to be in. I think we all know it. Do not all young men fall in love first with a chimera . . .?’

‘I am a chimera,’ Andy said, raising his hands like claws, putting on his monster’s face. ‘I was a teenage chimera.’

‘I’m in love with a darling young chimera,’ Jim sang quietly.

‘It is only later that this idealized woman transmigrates to the body of a living person – and the trouble starts. At this point in the male’s life there enters the unknown Max Factor.’

Dutiful laughter was struck up in the lecture-room, disconcerted by a jeering bassoon from the back, closely followed by an operatic facsimile of agonized death.

‘Hey, Charlie,’ Andy said, nudging him. ‘Waken up. Ye’re missing all the riotous fun. We’ve just had a joke.’

‘Ah wondered what the smell wis,’ Charlie said. ‘Hell, Ah wish he would give ye some sign, like dropping a hanky or something. Ah always miss his wee jokes.’

‘Ah know why

you

missed it, too,’ Jim said. ‘You were off to Mary-land there again.’

Jim’s guess was right. Charlie had been thinking about Mary. Since her last letter his mind had developed a kind of stutter and he couldn’t get past thinking of what she had written. He closed his mind on the lecture-room again, locking out Professor Aird’s insistent voice. He thought again of

the sentence that his mind had been pushing out like a mad teleprinter for three days until he had barely room for another thought. ‘It’s five days since “you-know-what” was due and didn’t come and what do I do?’ Well, what did she do? Take up knitting? He liked the euphemism – ‘you-know-what’. He knew what, all right. She had always been very regular, she said. Maybe a day either way. This was five. And now three more. That made it eight – the simple arithmetic of paternity. Five plus three equals daddy. Every day was another step up the aisle. He didn’t object to marrying Mary. He wanted to marry her – eventually. He had calculated on that pleasure coming along in time. But he didn’t want his future express delivery. He couldn’t use it just now. He had two more years of university after this one, if he took honours. It was a good thing it wasn’t a course in premarital relations. He wouldn’t win any medals for that. Even if he told his father – who had enough to worry him without the patter of tiny bastards – and even if he squared it up with Mary’s folks, where was the money to come from? What did you do? Sue the contraceptive makers for the price of the reception? It was hopeless. Why did even the most natural things you did have to pivot on economy? They had you every way. All the good things were either padlocked with morality or tagged with money. Money. Mon-ey! God of our fathers, we worship thee in all thy glorious manifestations, from the mighty fiver to the sterling pound, yea even to the little pennies of the pocket. Without thee, what is man? He is even as a pauper and the glories of the world shall not profit him, neither shall they yield him aught of joy. Without thee, what may a man do? Pray. That was all you could do. Pray to Nature to take her erratic course. And Nature said, let there be blood. And there was blood. That was all he could hope for. That was all he could do. Pray. ‘More things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of.’ Well, he would put it to the test.

‘Of course, it is hoped that Juliet will marry Count Paris. But in reciprocating Romeo’s love she helps to create the

microcosm of sanity and love within the macrocosmic hate and senseless conflict of Verona.’

The voice droned on, buzzing against Charlie’s brain like a fly against a window-pane. He was worried about telling his father, not because of what he would say, but because he set so much store by Charlie’s going to university, and it was enough of a struggle without adding mendicant grandchildren. That was the worst part of all, the way you inevitably impinged on other people in these things. If it had just been a matter of themselves it wouldn’t be so bad. But you were all connected by invisible wires so that anything you did provoked a response in others. He could imagine Mary’s father doing his fireside Stoic about the whole thing, bleeding quietly all over the place, stabbed to the heart by Charlie’s treachery. And her mother. That was going to be worse. Mrs Littlejohn. She was bad enough at any time. She was a conning-tower for misfortune. She saw it coming when nobody else could, dim in the distance, and she put out the welcome mat for it. Charlie could almost sense the forthcoming cataclysm, like earth termors. Her shock would be seismic. It always was, even in trivial matters. She enclosed herself in a crinoline of rigid convictions and seemed constantly offended that the rest of the world was out of step. Every time she moved, she rustled with bigotry. In her presence Charlie always felt like being in a room cluttered with omate bric-à-brac of cut glass where you couldn’t make a wrong move or say a wrong thing without another transparent prejudice being smashed. When she heard of this, the noise was going to be deafening. Charlie didn’t relish playing the bull to her china shop.

‘But can he, in fact, openly profess his love for Juliet? Today, no doubt, things would be different. But we must try to think ourselves into the social climate of his time and society. We must try to appreciate that the very air he breathes has a texture different from that which we inhale at this moment in this room. In our society, for better or for worse, the reins are being given more and more into the

hands of youth. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that crupper, bit, and bridle are being dispensed with altogether and the individual clings only to the mane of natural instinct to guide the course of his life. This is doubtless a sad reflection on the social horsemanship of your elders. Be that as it may. It is not so in Verona. For Romeo, personal choice is gravely restricted because of the social pressures under which he lives. Authority is to a degree sacrosanct. Romeo owes allegiance to his father, who in turn owes it to the duke. He is subject to a strict authoritarian hierarchy. So too, of course, is Juliet. Witness old Capulet’s outbursts at her unwillingness to accept Paris as a husband. How then, in this atmosphere of claustrophobic conformity, can Romeo fulfil his personal feelings without coming into direct and open conflict with this hierarchy and authority? Here lies Romeo’s problem.’

Stuff Romeo, Charlie thought. He thought he had problems. He didn’t know the half of it. ‘Oh, speak again, bright angel,’ and tell me that ‘I-know-what’ has come at last.

‘Montague and Capulet are the pincer-jaws between which Romeo and Juliet are caught, crushing them in the end, but also in so doing squeezing out of their tragic love an intensity and a poignancy which would not otherwise have been.”

Montague and Capulet? They weren’t in the same league as Mrs Littlejohn. She was Verona all on her own. Maybe she was just sharpening her pincer-jaws at that very moment, and looking out her thumbscrews.

‘Accident plays its part, it is true, and the play is the weaker for it. Nevertheless, the tortuous sequence of events that culminates in a double suicide as well as the deaths of Paris and of Tybalt to balance that of Mercutio stems directly from the need for constant subterfuge that is imposed on the two lovers. Therefore, where does the blame finally lie?’

With the rubber tree? Perhaps that was it. His tragedy might have its origin in the dim recesses of some Malayan forest where one tree among thousands had been smitten with

the dreaded rubber-worm. And now he was reaping the fruits. ‘Fruits’ was right.

‘Accident, yes. But accident nurtured by hate. Accident which has as its foster-parent human error. Notice that accident enters into it only

after

the initial damage has been done by human agency. Notice human error. Notice human guilt. Notice . . .’

‘Notice the time, Jimsy,’ Andy muttered. ‘For God’s sake, man, even intellectuals have to eat. Ah’ll be reduced tae gettin’ beetled into this desk in a minute.’

Charlie smiled to himself. Andy’s voice summoned him back to commonsense. He looked at Jim and Andy, waiting like horses at the gate to go and get fed. There were only a couple of minutes to go. Just being with them helped. With them, through banter and familiar jokes and clowning, he could build up a synthetic atmosphere, like an oxygen tent, in which he could breathe easy again and the pulse of panic could settle back to a contrived normalcy. All he wanted was for things to go on the way they were going without disturbance. He would be happy to go on like this for another two years, attending lectures, carrying on interminable conversations of abysmal profundity in the Students’ Union, working in the reading-room, having a drink with Andy and Jim in the beer bar, going home for a week-end every month or so. It was a good set-up. He had no complaints, if only this thing would blow over. And there was still some hope. Perhaps the crisis was over already and he didn’t know it. Perhaps a letter was on the way, telling him it was all right. He hoped he knew for certain before next week, anyway. He had examinations then. And he couldn’t settle to work with this hanging over him. Perhaps he would know before then. He might go home at the week-end, although he hadn’t intended to be home for a fortnight yet. If he hadn’t heard by the week-end, he would go home and see Mary. Having made a definite decision, however small, he felt a little better. That meant he had three more days before he could do anything positive, and the best thing he could do meanwhile was to try

and carry on just as usual. There was no point in doing trouble’s work for it. If the situation was going to give way under him, it would. And when it did it would be bad enough without his making it worse by anticipation. There was nothing he could do just now. Any minute they would be going down to the Union for lunch and maybe have a game of snooker before going up to the reading-room to work.

‘But Verona can only be purged of its evil hatred through the deaths of these two people, people themselves innocent of that hatred.’

‘Come on, come on,’ Andy said. ‘Ring the bell, verger, ring the bell, ring.’

‘Hell, we’re gonny have tae shoot this man,’ Jim said.