Resident Readiness General Surgery (9 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

A

dmit: indicates which ward the patient is admitted to and under which attending.

D

iagnosis: the patient’s diagnosis.

C

ondition: the general acuity of the patient (eg, stable, guarded, critical).

V

itals: how often you want nurses to perform vital signs (if you write “per routine/protocol,” know what that means for each ward).

A

llergies: the patient’s known allergies, including the reactions that occur.

N

ursing: these are specific orders to nursing staff for patient care (eg, dressing changes, tube management).

D

iet: what the patient is allowed to eat. Be specific. Nothing (ie, NPO) is a diet.

A

ctivity: what the patient is allowed to do and also what the nursing staff will encourage the patient to do (eg, ambulate 3 times per day).

M

edications: inpatient medications the patient needs. Include prn medications for possible symptoms the patient may experience (eg, Zofran for nausea, Dilaudid for pain, Colace for constipation).

L

abs/radiology: think critically about what labs the patient needs. For example, does the patient really need a daily CBC with differential or will a standard CBC suffice?

CALL-HO

: this set of orders tells the nurses when to notify you. Typically these are abnormalities of vital signs, but also include patient-specific details (eg, hoarseness or expanding neck mass after thyroid surgery).

Following a simple mnemonic each time you write admission orders can provide a clear plan of care and prevent many calls to correct omissions. This technique is still useful in the age of the electronic medical record (EMR). While the EMR often provides order sets or checkboxes, even the most detailed admission order sets were designed for a disease and not a patient—there is no “Mr. Smith order set.” You should therefore systematically check your work (ie, run through this or some other mnemonic) before finalizing the orders.

Anther important aspect of admission ordering that is often overlooked is medication reconciliation. This process clarifies the patient’s home medications and determines what should be continued or held on admission. This process should extend beyond simply finding out the names and dosages of medications; it should also include why the patient is taking these medications. Does the patient with prn Xanax take her pills once per week or 3 times per day? If the answer is 3 times a day, then this patient will likely go into benzodiazepene withdrawal if the medication is withheld. Is the patient on metoprolol taking it for high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, or atrial fibrillation? Each answer has different implications for this medication and the care of the patient. Unfortunately, it is the rare patient who will remember every medication, dosage, and reason for the prescription. Using a patient’s old medical records, clinical notes, or discharge summaries will provide useful insight. When in doubt, ask a family member to bring in the actual bottles of medications the patient takes at home. If even that doesn’t work, you can call the patient’s pharmacy or PCP’s office.

AVOIDING COMMON ADMISSION MISTAKES

While the admission process may seem daunting, there are several common pitfalls that can be easily avoided. The first is to recognize when you need help. This is not a question of being weak or a challenge to your ego, but rather a matter of patient safety. There will be times when there are too many admissions to be seen in a reasonable amount of time or there are too many sick patients. These are the times to tell your chief that you need some backup. Interns need to keep their

chiefs informed of pertinent or unexpected events, such as changes in a patient’s condition or concerning lab/radiology results. Another common pitfall is not following up on a test; every physician who orders a test is responsible for checking the result. For surgeons this includes looking at the radiology images themselves, not just reports. Finally, some patients are anything but routine. These patients need everyone to be clear about how to proceed, and that includes the nursing staff. When good communication exists between nurses and interns, it is to the benefit of the patient and the intern.

GO GET ’EM

To take the most benefit from each admission you have to be an active participant. While a good intern will gather information thoroughly, present it concisely, and execute the plan conscientiously, a great resident will be thinking, “What would I do if I were in charge?” With each new admission you should see the patient, make a plan, listen to the attending, and keep score. The pursuit of the perfect score is what keeps surgeons operating and helping one patient at a time.

A 56-year-old Female Status Post Motor Vehicle Accident

A 56-year-old Female Status Post Motor Vehicle Accident

Ashley Hardy, MD and Marie Crandall, MD, MPH

While on your night float rotation, you and other members of the surgical team are called to the emergency department (ED) in response to the activation of the trauma team. As the patient is being wheeled into the trauma bay, the paramedics inform you that the patient is a 56-year-old female who was a restrained driver in a motor vehicle crash (MVC). She rear-ended a stopped car going at a speed of approximately 45 mph. There was no loss of consciousness at the scene and the patient appears alert. The paramedics report that the patient has obvious deformities of her proximal upper right arm and distal left thigh. You hear your senior resident announce that she is going to begin the primary survey.

1.

Why was it appropriate to initiate a trauma activation in this patient?

2.

What is your role during this trauma? Where should you stand?

3.

What is the goal of the trauma primary survey?

TRAUMA PRIMARY SURVEY

Answers

1.

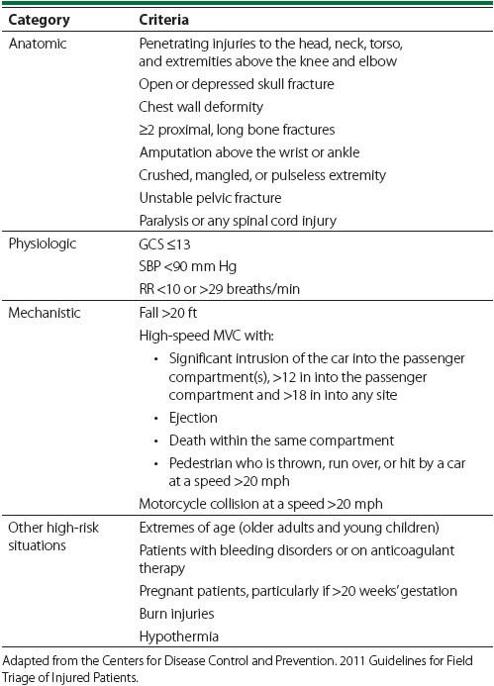

Per CDC guidelines, the trauma team should be activated if 1 or more specific anatomic, physiologic, and mechanistic criteria are met as illustrated by

Table 7-1

. The patient in this scenario meets criteria for trauma team activation given her involvement in a high-speed MVC and likelihood of her having at least 2 proximal long bone fractures.

Table 7-1.

Anatomic, Physiologic, Mechanistic, and Other High-risk Criteria for Trauma Activation

2.

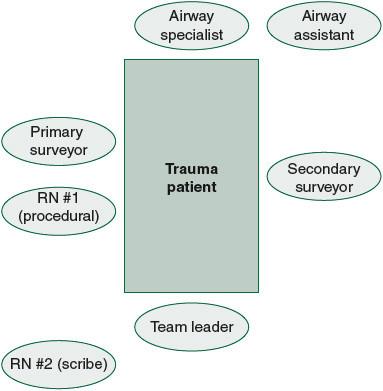

Although minor variations may exist from institution to institution, the trauma team at most academic medical centers consists of a team leader, an airway specialist, primary and secondary surveyors, and ED nurses. Note that depending on the nature of the injury, other specialized staff (ie, orthopedic surgery or neurosurgery) may also be present. It is imperative that members of the trauma team are aware of their roles to ensure that the best care possible is given to the traumatically injured patient. Trauma team members and their respective job descriptions are listed below and a diagram of their position with respect to the patient is illustrated in

Figure 7-1

:

Figure 7-1.

Trauma team. Diagram of the various members that comprise the trauma team and their position with respect to the traumatically injured patient.

Team leader

(trauma surgery attending or the senior surgical resident until the attending arrives):

•

Obtains history from Emergency Medical System (EMS) staff

•

Directs team members on how and when to perform their respective tasks

•

Orders the administration of drugs, fluids, or blood products

•

Performs or assists with any lifesaving procedures

•

Determines the patient’s disposition (ie, additional imaging, OR, ICU)

•

Discusses the patient’s status with the family members

Airway specialist

(2 people—anesthesiologist, ED attending, or senior residents of either specialty with 1 person serving as an assistant):

•

Controls the airway, ensuring patency

•

Performs any airway interventions, excluding the performance of a surgical airway

•

Maintains cervical spine stabilization

Primary surveyor

(surgical resident):

•

Performs the primary survey, relaying all pertinent findings to the team

•

May perform the secondary survey, relaying all pertinent findings to the team

•

Performs or assists in the performance of any lifesaving procedures at the direction of the team leader

Secondary surveyor

(surgical resident or intern—this is you!):

•

Assists with the “exposure” aspect of the primary survey (see below) and applies warm blankets

•

May perform the secondary survey, relaying all pertinent findings to the team

•

Performs or assists in the performance of any lifesaving procedures at the direction of the team leader

ED nurses

(usually 2, with 1 person performing procedures and 1 serving as a recorder):

ED nurse #1 (procedural).

Obtains vital signs:

•

Establishes peripheral intravenous (IV) access for the administration of drugs, fluids, or blood products

•

Inserts indwelling devices (ie, nasogastric or orogastric tubes and urinary catheters) at the direction of the team leader

ED nurse #2 (scribe).

Records all vital and physical exam findings obtained from the primary survey:

•

Lists in chronological order any interventions performed on the patient

Note that, as a new intern, you should position yourself next to the patient, most likely next to the primary surveyor or on the patient’s left. You should expect to aid with removing clothing and getting warm blankets. You may also be called on to perform all or part of the secondary survey, perform the FAST exam, or generally be another set of hands. As you become more experienced, you may be able to move into the role of primary surveyor, especially for those trauma activations that are less acute.

3.

The goal of the trauma primary survey is to identify and immediately treat any life-threatening injuries. This is in contrast to the secondary survey, the purpose of which is to ensure that no other major injuries were missed and to identify any additional, non–life-threatening injuries.