Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore (38 page)

Read Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore Online

Authors: James T. Patterson

Tags: #20th Century, #Oxford History of the United States, #American History, #History, #Retail

W

ITH ACCOMPLISHMENTS SUCH AS THESE

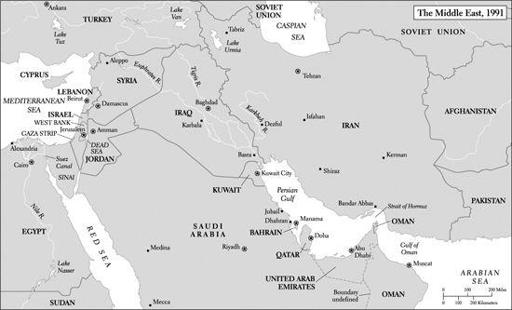

, Bush might well have expected to go down in history as one of America’s more skillful presidents in the management of foreign policy. By the time he left office, he was especially well remembered as the president who led a carefully established and formidable international alliance into a war against Iraq. Though the war did not prevent instability from returning to the deeply troubled Middle East, the coalition swept to triumph after triumph in the fighting itself.

In the eyes of Bush—and of many other heads of state—the major source of trouble in the region was President Saddam Hussein of Iraq. After taking power in 1979, Hussein had come to imagine himself as a modern Nebuchadnezzar who would lead the Arab world to magnificent heights. Among his idols were Hitler and Stalin. Over time he built a string of lavish palaces for himself and his family. Statues and portraits of him proliferated in the country. In 1980, he opened war against neighboring Iran, a far larger nation. The fighting lasted eight years, during which Hussein used chemical weapons against the Iranians, before the war sputtered to an inconclusive end in 1988. During this time Hussein supported efforts to manufacture nuclear bombs, and he murdered hundreds of thousands of his own people, most of them Kurds and Shiites who were restive under the oppressive rule of his tightly organized clique of Sunni Muslim followers.

30

In March 1988, he authorized use of chemical weapons in the Kurdish village of Halabja, killing 5,000 people in one day.

Reagan administration officials, believing Iran to be the bigger threat to stability in the Middle East, had turned a mostly blind eye to Hussein’s excesses and had cautiously supported his regime between 1980 and 1988. Hussein benefited during the Iran-Iraq war from American intelligence and combat-planning assistance. As late as July 1990, America’s ambassador to Iraq may have unintentionally led Hussein to think that the United States would not fight to stop him if he decided to attack oil-rich Kuwait, Iraq’s neighbor to the south. But the Iraqi-American relationship had always been uneasy, and it collapsed on August 2, 1990, when Iraq launched an unprovoked and quickly successful invasion of Kuwait. Bush, sensitive to memories of the quagmire of Vietnam, and conscious of the potentially vast implications of military intervention, was taken aback by Iraq’s bold aggression. Britain’s “Iron Lady,” Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, was said to have tried to stiffen his spine. “Remember, George,” she was rumored to have warned, “this is no time to go wobbly.”

31

In fact, Bush needed no stiffening. Quickly imposing economic sanctions on Iraq, he emerged as the strongest voice within the administration against Hussein’s aggression. Declaring, “This will not stand,” the president overrode warnings from advisers, notably Powell, that war against Iraq would be costly and dangerous. Cheney and Powell estimated at the time that as many as 30,000 American soldiers might die in such a conflict.

32

Sending Secretary of State Baker on a host of overseas missions, Bush succeeded in enlisting thirty-four countries in a multinational coalition that stood ready to contribute in some way to an American-led fight against Iraq. In late November, Bush secured passage of a U.N. Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force to drive Iraq from Kuwait if Hussein did not pull out by January 15, 1991. The resolution passed, twelve to two, with the Soviet Union among the twelve. China, one of the five nations with a veto power, abstained. Only Yemen and Cuba dissented.

33

From the beginning, however, Bush realized that Hussein, who claimed Kuwait as Iraqi territory, had no intention of backing down. Like Carter, who had pronounced that America would go to war if necessary in order to prevent enemies from controlling the Persian Gulf, he was prepared to fight against aggressors in the region. So while the wheels of diplomacy were turning, he energized the Powell Doctrine. No longer fearful of Soviet military designs on Western Europe, he pulled a number of American troops from Germany in order to bolster what soon became a formidable coalition fighting force. The coalition, which had the nervous support of several Muslim nations (including Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey)—and which was to rely heavily on the willingness of Saudi Arabia to serve as a staging area—ultimately included troops from five Arab states. More than 460,000 American troops, 1,500 aircraft, and sixty-five warships moved to the Persian Gulf region.

34

As Bush prepared for a conflict that he believed to be inevitable, he was reluctant to seek the approval of the heavily Democratic Congress. In January 1991, however, he succumbed to political pressure urging him to do so. As he had anticipated, most Democrats opposed him. Some charged that the president, who had made millions in the oil business, was eager for war in order to protect wealthy oil interests in the United States. Others argued that Hussein should be subjected to further economic and diplomatic pressure, which, they said, would force him to come to terms. Some foes of war worried that the president might authorize an invasion and takeover of Iraq itself, thereby miring the United States in a drawn-out, potentially perilous occupation.

Bush got what he wanted from the Hill, though by narrow margins. By heavily partisan votes, Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing war pursuant to the U.N. resolution of November 1990. The vote in the House was 251 to 182, with Republicans approving, 165 to 3, and Democrats opposing, 179 to 86. In the Senate, which decided on January 11, the tally was 52 to 47, with Republicans in favor, 42 to 2, and Democrats against, 45 to 10. Among the handful of Senate Democrats who voted for the resolution was Al Gore Jr. of Tennessee. Among those opposed was John Kerry of Massachusetts.

35

This was the closest senatorial vote on war in United States history.

There was no doubting that Hussein’s conquest threatened Western oil interests. It was estimated at the time that Iraq produced 11 percent, and Kuwait 9 percent, of world supplies. Neighboring Saudi Arabia, the leading producer, accounted for 26 percent. The Persian Gulf area had more than half of the world’s proven reserves. The United States, having become increasingly dependent on overseas production, at that time imported a quarter of its oil from the Gulf. Fervent supporters of the war, such as Defense Secretary Cheney and Wolfowitz, were keenly aware of the large economic assets that Iraq’s conquest had threatened.

36

In defending his position, however, Bush insisted that the key issue was Iraq’s naked aggression, which must not be tolerated. He also maintained that Hussein was secretly developing the capacity to make nuclear bombs.

37

He displayed special outrage at Hussein’s cruel and murderous treatment of his own people. Hussein, he charged, was “worse than Hitler.” When the U.N. deadline of January 15 passed, he wasted no time in going to war, which started on January 16.

The coalition attack featured two phases. The first entailed massive bombing of Kuwait, Baghdad, and other Iraqi cities and installations. This lasted thirty-nine days. Coalition aircraft fired off 89,000 tons of explosives, a minority of them laser-guided “smart bombs” and cruise missiles, at these targets. The bombing was frightening, causing the desertion of an estimated 100,000 or more of the 400,000 or so Iraqi troops that were believed to have been initially deployed. It was also devastating. The air offensive destroyed Iraq’s power grid and sundered its military communications. A number of contemporary observers thought that the bombing created severe food shortages, damaged facilities guarding against water pollution, provoked outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, and seriously disrupted medical care.

38

Some of this air war was featured on network television and on Cable News Network (CNN), which since its creation in 1980 had established itself as a successful network providing twenty-four-hours-a-day news of events all over the world. CNN offered mesmerizing coverage from Baghdad of streaking missiles and flashing explosions. Iraqi Scud missiles were zooming off toward targets in Israel and Saudi Arabia, and American Patriot missiles were shooting up to intercept them. Though one of the Scuds (of the eighty-six or so believed to have been fired during the war) killed twenty-eight American military personnel in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, most of them did no serious damage. American claims to the contrary, later studies concluded that the Patriots had relatively little luck hitting the Scuds. The Scuds, however, did prompt a widely told joke: “Question: How many Iraqis does it take to fire a Scud missile at Israel? Answer: Three, one to arm, one to fire, the third to watch CNN to see where it landed.” President Bush avidly followed CNN, which he said was a quicker source of news than the CIA.

With Iraqi defenses rendered virtually helpless, coalition forces undertook the second stage, Operation Desert Storm, of the Gulf War. Led by American general Norman Schwarzkopf, this was the ultimate demonstration of the Powell Doctrine, which called for the dispatch of overwhelmingly superior military power. Some of the troops used GPS gadgetry enabling them to navigate the desert. In only 100 hours between February 23 and 27, this army shattered Iraqi resistance. Tens of thousands of Iraqi troops were taken prisoner. Most of the rest fled from Kuwait into Iraq. Unreliable early estimates of Iraqi soldiers killed varied wildly, ranging as high as 100,000.

The actual numbers, most later estimates concluded, had probably been far smaller. One carefully calculated count, by a former Defense Intelligence Agency military analyst, conceded that estimates varied greatly, but set the maximum number of Iraqi military casualties from the air and ground wars at 9,500 dead and 26,500 wounded. His minimum estimates were 1,500 dead and 3,000 wounded. Civilian deaths, he added, may have been fewer than 1,000. American losses may have been tiny by comparison. Most estimates agreed that the number of United States soldiers killed in action was 148 (at least 35 of them from friendly fire) and that the number who died in non-battle accidents was 145. A total of 467 American troops were wounded in battle. These same estimates concluded that a total of 65 soldiers from other coalition nations (39 from Arab nations, 24 from Britain, 2 from France) had also been killed in battle.

39

As Iraqi soldiers fled on February 27, Bush stopped the fighting. The abrupt end allowed many of Hussein’s assets, including Russian-made tanks and units of his elite Republican Guard, to escape destruction or capture. When the coalition armies ground to a halt, they left Baghdad and other important cities in the hands of their enemies. Saddam Hussein and his entourage licked their wounds but regrouped and remained in control until another American-led war toppled him from power.

Needless to say, the decision to stop the fighting aroused controversy, much of which resurfaced twelve years later when President George W. Bush (Bush 43) sent American troops into another war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Bush 41 called off the fighting in 1991 for several reasons. First, he and his advisers were said to have worried that coalition forces would be accused of “butchery”—a “turkey shoot”—if they slaughtered near-defenseless Iraqi soldiers in full flight on a “Highway of Death” into Iraq. He insisted, however, that his exit strategy had always been clear: to free Kuwait and to drive Hussein back into Iraq. This had also been the mandate of the U.N. and congressional resolutions. “I do not believe,” Bush said later, “in what I call ‘mission creep.’”

40

In refusing to go after Saddam Hussein, the president was acutely aware of how difficult it had been to locate Noriega in the immediate aftermath of the American assault on Panama, a far smaller nation. Bush pointed out another important consideration: Some of America’s coalition partners, such as Syria and Egypt, feared a disruption of the balance of power in the Middle East. Worried that unrest in Iraq would spread and threaten their own regimes, they opposed a wider mission that might have toppled Hussein from power.

Bush also figured that Operation Desert Storm had badly damaged Iraq’s military capacity. It had in fact helped to finish off Hussein’s never well managed efforts to build nuclear bombs. To ensure that Iraq would remain weak in the future, Hussein was forced to agree to a prohibition of imports of military value and to refrain from rearming or developing weapons of mass destruction. United Nations inspectors were authorized to oversee these restrictions and remained in Iraq into 1998. The U.N. also established “nofly zones” over Shiite and Kurdish areas of Iraq, from which Hussein’s aircraft were prohibited. An embargo on the export for sale of Iraqi goods, notably oil, was expected to limit Hussein’s capacity to rearm. These economic sanctions (combined with Hussein’s greed and callousness toward his own people) are believed to have been a cause of considerable suffering among the people of Iraq before December 1996, when Hussein finally agreed to a U.N.-managed “oil-for-food” arrangement that enabled him to buy food and medical supplies from proceeds of limited oil sales.

41