Rifles: Six Years With Wellington's Legendary Sharpshooters (38 page)

Read Rifles: Six Years With Wellington's Legendary Sharpshooters Online

Authors: Mark Urban

Tags: #Europe, #Napoleonic Wars; 1800-1815, #Great Britain, #Military, #Other, #History

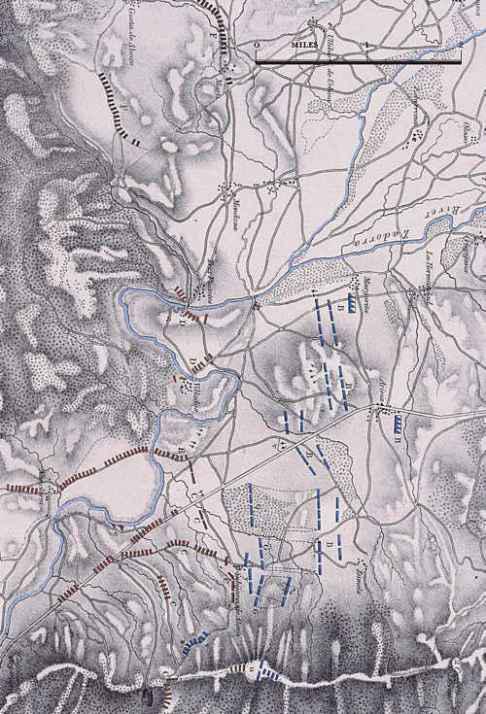

11 Mitchell’s view of Fuentes d’Onoro. ‘Q’ shows the Light Division covering the withdrawal of the 7th Division, which took up new positions at ‘R’. Once Wellington had pulled back his right flank, the 1st and Light Divisions occupied positions at ‘T’. It was from there that Guards and 95th skirmishers went into the Turon valley.

12 Vitoria. The Light Division’s attacks are marked ‘D’, Barnard’s Brigade being the lefthand one which found its way around the hairpin bend in the Zadorra river. Wellington’s grand design can be seen with the arrival of the flanking columns, ‘F’ (3rd and 7th Divisions). The main French defensive line, ‘B’, was pushed pack as the British broke their centre at Arinez.

13 Wellington breaches the French Pyrenean defensive line at Nivelle with attacks by the 3rd, 4th, 7th and Light Divisions, marked ‘L’. They fought through their initial objectives to positions marked ‘N’.

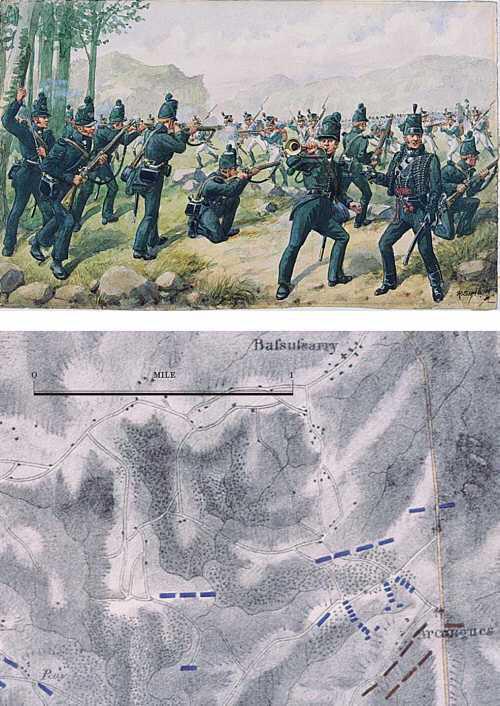

14 Top: a later portrayal by Simkin of the 95th fighting in the Pyrenees. Already, a certain mythologising of events shows through, for example with the pristine uniforms. Bottom: the Battle of the Nive, showing Arcangues and Bassussary, scene of several Light Division fights in November and December 1813.

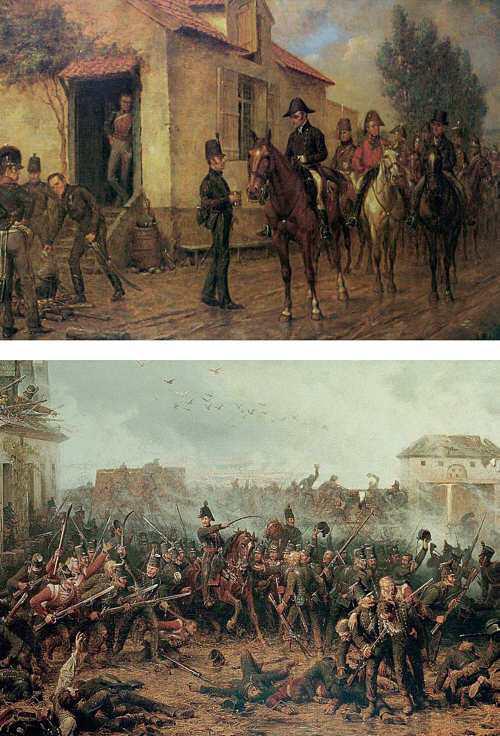

15 Top: Morning at Waterloo by Aylward: Kincaid, Simmons and Barnard were probably all witnesses to this scene as riflemen offered a morning brew to the passing Wellington. Bottom: the fierce fighting in La Haye Sainte involved mostly riflemen of the King’s German Legion but also, just behind the wall pictured here, Leach’s companies of the 1st/95th.

Departures

1 ‘Just before 6 a.m.’: general descriptive detail of the embarkation has come from several eyewitnesses, including George Simmons, A British Rif

leman, Gr

ee

nhill ed

ition, 1986; William Green,

A Brief Outline of

Travels and Adventures of William Green

, Coventry, 1857; and notes from the manuscript journals of Jonathan Leach and some other officers held at the Royal Green Jacket Museum in Winchester.

– ‘This, my dear parents, is the happiest moment of my life’: Simmons’s letter is one of those, along with his campaign journal, reproduced in A

British Rifleman

.

– ‘the commanding officer’s intent’: so says Simmons.

2 ‘Private Robert Fairfoot marched in the ranks’: details of Fairfoot’s background come from various official documents in the Public Record Office, Kew. His age and other information are in WO 25/559, details of his Surrey Militia service in WO 13/2089 to 13/2095.

3 ‘One of the old hands commented contemptuously’: Green.

– ‘assert they were headed to help the Austrians’: Simmons’s letter says the destination is a ‘profound secret’, although it is supposed to be Portugal or Austria.

– ‘There had been wives on the last expedition’: their fates are suggested by Benjamin Harris, a 1st Battalion rifleman who served in the Corunna campaign of 1808/9 but did not embark with the others on 25 May 1809. I have used the edition of Harris’s memoirs edited and published by Eileen Hathaway’s Shinglepicker Press in 1995 as

A Dorset Rifleman

.

– ‘It was such a parting scene’: Green.

4 ‘O’Hare’s 3rd Company … went aboard the

Fortune

’: Simmons.

– ‘For some of the men, like Private Joseph Almond’: details of Almond’s service have been extracted from the pay and muster lists, WO 12/9522, WO 17/217, WO 25/2139.

4 ‘some of the young officers took the opportunity to go ashore’: including Captain Jonathan Leach,

Rough Sketches of An Old Soldier

, London, 1831. Leach was to prove the most prolific of the 95th’s later author-officers; in addition to his books I have had access to the copy of his unpublished manuscript journal produced by Willoughby Verner when working on his

History and Campaigns of the Rifle Brigade

.

5 ‘Private Fairfoot knew a fair bit about desertion’: details of Fairfoot’s vicissitudes emerge from the Royal Surrey paylists, WO 13/2089 to 2095

6 ‘A very amusing plaything’: this description of the 95th came from Lord Cornwallis in a letter of 24 October 1800, and was reproduced in the

Rifle Brigade Chronicle

, 1893, and subsequently in Verner’s

History

. Quite why Cornwallis, a veteran of much irregular fighting in America and India, should have been so short-sighted about the value of a rifle regiment is a mystery.

– ‘The order of the day was to bombard the sea-fowl’: this description comes from Leach,

Rough Sketches

.

– ‘Tom Plunket, in 3rd Company, along with Fairfoot’: Tom Plunket’s saga is contained in Costello,

The True Story of a Peninsular Rifleman

, the Shinglepicker version of Costello’s memoirs, published in 1997.

7 ‘he’d loaded his razor and fired that at the French’: this anecdote of Brotherwood, along with comments on his character, is contained in Harris.

– ‘Costello had been seduced by the yarns his uncle spun’: Costello.

– ‘it was a deeply unhappy battalion run on the lash and fear’: Capt. B. H. Liddell Hart (ed.),

The Letters of Private Wheeler

, London, 1951. By a stroke of serendipity, Wheeler served in the same militia battalion as Fairfoot and describes its unhappiness under a regime of fear in his early letters. Wheeler volunteered in the 51st.

– ‘the fickle dictates of fashion led to hundreds like him being cast out of work’: F. A. Wells,

The British Hosiery and Knitwear Industry

, London, 1935, describes the depression in this trade and its causes. Pay lists and casualty returns reveal that dozens of the Leicester Militia men had been weavers. WO 25/2139 gives Brotherwood’s trade as ‘stocking weaver’.

8 ‘the great majority had never purchased a commission’: this is my own research based on many sources, including War Office files and Royal Green Jackets archives. The one-time purchasers included Harry Smith and Hercules Pakenham.

– ‘officers and men alike knew him as a foul-tempered old Turk’: the term ‘obstinate old Turk’ is used by Harry Smith to describe O’Hare in

The

Autobiography of Lieutenant General Sir Harry Smith

, London, 1901.

– ‘An allowance of

£

70 or

£

80 was considered quite normal’: see, for example, Cooke of the 43rd, one of the battalions brigaded with the Rifles.

8 ‘One young lieutenant … was the main provider for his widowed mother and his eight siblings’: this was John Uniacke. His family circumstances emerge from WO 42/47U3, papers relating to the later financial distress of his mother.

9 ‘can never be taught to be a perfect judge of distance’: Colonel George Hanger, a veteran of the American wars, in his 1808

Letter to Lord

Castlereagh

, cited by David Gates in his

The British Light Infantry Arm

, London, 1987.

Talavera

11 ‘The quartermaster and a party of helpers soon appeared with dozens of mules they had bought in Lisbon’: this detail and many others in this opening passage from Simmons’s journal and letters.

– ‘There was an official allowance of pack animals’: these are set out in the volumes of General Orders published by Wellington’s headquarters. These papers, printed on an Army press, were collected and bound by various staff officers and individuals in the Peninsular Army, and quite a few have survived. I consulted those in the National Army Museum and the stupendous private collection of John Sandler.

– ‘The subaltern officers – thirty-three of them in the battalion’: this is my count of these officers on the 1st/95th’s pay rolls, not the standard establishment.

– ‘A pack animal might cost

£

10 or

£

12’: figures on the costs of various items emerge in many journals or sets of letters, including Cooke, Hennell and Gairdner.

12 ‘his “black muzzle” peered over’: this description of Craufurd belongs to Harry Smith in his autobiography. Smith also comments on the squeaky voice.

– ‘Craufurd’s character was … described by one newspaper’:

Cobbett’s

Political Register

, 25 October 1806.

– ‘he would find himself again and again coming back to the memory of Buenos Aires’: this letter from Craufurd to his wife is dated 3 December 1811 and is quoted in a biography of Black Bob written by Michael Spurrier, which drew extensively on family papers. The unpublished typescript was kindly loaned to me by Caroline Craufurd, one of the general’s descendants. The key Craufurd letters remain in the family’s possession.

13 ‘Captain Jonathan Leach, commander of 2nd Company, wrote in his diary’: Leach’s MS Journal, RGJ Archive, this passage is also quoted in Verner.

13 ‘The Standing Orders set out’: I used ‘The Standing Orders of the Light Division’, Dublin, 1844.

15 ‘You have heard how universally General Craufurd was detested’: Leach MS Journal, RGJ Archive. Verner’s typescript of Leach’s journal is not complete (it is missing early 1812) but the great majority of his narrative can be found scattered in many different packets of Box 1 of the RGJ Archive.

– ‘We each had to carry a great weight’: this passage and the preceding comment about filling water bottles, Costello.

– ‘They began at 2 a.m. on the’: details, Leach MS Journal.

18 ‘They had drawn up their forces in two waves’: this passage on the centre at Talavera relies pretty heavily on Sir Charles Oman’s synthesis of eyewitness accounts in Vol. II of

A History of the Peninsular War

, Oxford, 1903.

21 ‘the last ten miles the road was covered’: John Cox MS Journal. Cox was a lieutenant in the 1st/95th at the time. His handwritten journals reside in Dublin, but Verner copies certain passages and these remain in the RGJ Archive.

– ‘The horrid sights were beyond anything I could have imagined’: Simmons.

22 ‘the feelings which constant hunger produces’: Leach,

Rough Sketches

.

23 ‘This will perhaps be a subject of joy to you’: Craufurd’s letter to his wife is in the British Library, MSS Add 69441.

Guadiana

24 ‘The diary of one company commander read’: Leach MS Journal.

– ‘Brigadier Craufurd allowed his Light Brigade soldiers to shoot some pigs’: this incident appears in various accounts, including Leach,

Rough

Sketches

.

25 ‘Here we remained a miserable fortnight’: this was William Cox, brother of John, also of the 1st/95th, MS Journal, Verner’s copies in the RGJ Archive.

27 ‘Captain Jonathan Leach wrote in his diary on 27 August’: MS Journal.

– ‘Before Simmons knew it, he’d been collared by Craufurd’: Simmons.

28 ‘Beckwith was a model of self-control’: this picture of Beckwith is a collage drawn from Kincaid, Leach, Simmons, Smith and other Light Division diarists.

29 ‘Not a little disgusted, Beckwith asked him’: this priceless anecdote was evidently related by Barclay to Colborne, a subsequent CO of the 52nd, and is contained in his biography,

The Life of John Colborne, Field

Marshal Lord Seaton

, by G. C. Moore Smith, London, 1903.

– ‘One 95th officer described why it worked so admirably’: this description of the 95th’s system is contained in

Recollections and Reflections

Relative to the Duties of Troops Composing the Advanced Corps of An

Army

, by Lieutenant Colonel Leach, London, 1835 – one of Jonathan Leach’s lesser-known works, but full of interesting detail nevertheless.

30 ‘Every corps did harness and march forth to the river in that form except our own’: Leach,

Rough Sketches

.

– ‘British generals had learned many valuable lessons’: these lessons of America are culled from various sources, but principally General Sir William Howe’s orders of 1 August 1776.

31 ‘Craufurd felt the Army was guilty of forgetting many valuable lessons of the American war’: this point was made by Craufurd in speeches he made as a Member of Parliament in December 1803 and is quoted by Spurrier.

– ‘His Lordship … approves of your expending, for practice’: letter from the Adjutant General to Craufurd, 13 November 1809, in the published

Dispatches of the Duke of Wellington

, London, 1852.

– ‘Many of the battalion’s subalterns and even captains carried a rifle’: Costello states wrongly in his memoir (written many years later, of course) that he cannot see why officers did not carry rifles too. It is obvious from various accounts that Leach and Crampton among captains in the first battalion did, likewise many subalterns.

– ‘As soon as the rifleman has fixed upon his object’: this quotation comes from

Regulations for the Exercise of Riflemen and Light Infantry and

Instructions for Their Conduct in the Field

, London, 1803. This was a translated and slightly edited version of the first regulations produced five years earlier by the commanding officer of the new 5th/60th, Colonel Rottenburg.

32 ‘posted behind thickets, and scattered wide in the country’: this account of the American war is related in an article about the formation of the Rifle Corps (which became the 95th) in

The English Military Library

, no. XXIX, Feb 1801.

– ‘Rules and Regulations for the Army as a whole’: these are General Dundas’s

Rules and Regulations for the Formation, Field Exercise and

Movement of His Majesty’s Forces

, 1792.

– ‘Dundas thought any large-scale skirmishing’: these quotations come from Dundas’s

Principles of Military Movements, Chiefly Applied to Infantry

, London, 1788, a work that formed the basis of the later

Rules and

Regulations

. The fight between conservatives and reformers on tactics is also debated at length in David Gates’s

The British Light Infantry Arm c

.

1790–1815

, London, 1987. Moore’s quotation is also cited in Gates.

– ‘ape grenadiers’: this phrase was used by Leach in

Rough Sketches

to deride the orthodoxy.

33 ‘One was to stress the limited roles of the light-infantry’: this and the ‘born not made’ explanation emerge in

Essai Historique sur l’Infanterie

Légère

, Comte Duhesme, Paris, 1814. Colonel F. de Brack, an experienced French officer, stated in his classic

Light Cavalry Outposts

that ‘a man must be born a light cavalry soldier’.

– ‘The rifle, in its present excellence, assumes the place of the bow’: this quotation is from

Scloppetaria: or Considerations on the Nature and

Use of Rifled Barrel Guns

, London, 1808, published by Egerton. The author is given as ‘a Corporal of Riflemen’ but was actually Captain Henry Beaufroy of the 95th. The references to Egypt and Calabria are to recent British military expeditions (of 1801 and 1806) in which the British had acquitted themselves well against the French.

– ‘No printers, bookbinders, taylors, shoemakers or weavers should be enlisted’: this is Colonel Von Ehwald (sometimes spelt Ewald) in

A

Treatise Upon the Duties of Light Troops

, London, 1803. This work, another of Egerton’s, was translated from German and contains many fascinating ideas. Colonel William Stewart’s notions on recruiting in Ireland, cited later, seem to owe something to Ehwald. The decision to publish his works in English was a deliberate attempt to keep alive lessons of the American war, in which Ehwald had served as an officer in the Hessian Jaeger Corps.

– ‘if it were smaller the unpractised recruit would be apt to miss’: another quotation from the 1803

Regulations for the Exercise of Riflemen

.

– ‘The more experienced riflemen had trained in techniques for shooting at running enemy’: the use of little trolleys with targets mounted on them is described both by Beaufroy and Sergeant Weddeburne of the 95th,

Observations on the Exercise of Riflemen

, Norwich, 1804.

– ‘Eight out of ten soldiers in our regular regiments will aim in the same manner’: William Surtees,

Twenty Five Years in the Rifle Brigade

. I used the 1973 reprint.

– ‘One of the 95th’s founders had written in 1806’: this was Sir William Stewart, and his outline for the reform of the Army is quoted from in the Cumloden Papers, privately printed in 1871.

34 ‘Plunket, however, swore blind he would shoot the first officer’: this is based on Costello’s version of the incident.

35 ‘back in 1805 Beckwith had proven his aversion to flogging’: this anecdote in Surtees.

– ‘despite the wish of some officers to develop a more selective recruitment system’: e.g. Beaufroy in his book suggests the Rifles should be recruited only from the light companies of line regiments.

– ‘its composition had been roughly six Englishmen to two Scots and two Irish’: these estimates for 1809 are my own and are necessarily approximate, based on the details in muster rolls and casualty returns. My work on the Casualty Returns for January 1811 to December 1812 showed ninety-five English (including Welsh), thirty-three Irish and thirty-two Scots. Later things changed somewhat. WO 17/282, a Monthly Return dated 25 July 1814, gives a rare national breakdown of soldiers in the 1st Battalion 95th. Its lists: 63 sergeants (of which 31 English, 20 Scotch and 12 Irish); 48 corporals (of which 24 English, 8 Scotch and 16 Irish); 15 buglers (11 English, 2 Scotch, 2 Irish); and 748 privates (523 English, 87 Scotch, 138 Irish). The points of notes here are (a) that the rank and file of the regiment had become even more ‘English’ by 1814 due to recruiting efforts (b) the Scottish element had declined relative to the Irish because – I believe – of higher losses due to sickness, desertion and capture in the Peninsula, and (c) the pattern of heavier Scottish recruitment during 1800–5 and Irish in 1805–8 is reflected in the respective national ‘bulges’ for sergeants and corporals.

35 ‘Many officers felt the Irish were particularly prone to thieving’: the evidence of this stereotype can be found in several memoirs or diaries where an officer (e.g. Kincaid) notes that his Irish servant has stolen from him. We do not see similar records of English or Scottish thieving. It is worth noting that in General Orders the 88th or Connaught Rangers feature in scores of courts martial for theft and other misdemeanours during 1809–11. How far this represents a prejudice against this regiment with its strong Irish character, or how far it substantiates General Picton’s view of them as ‘robbers and footpads’, we can only guess.

36 ‘except in cases of infamy’: another quotation from Stewart’s ‘outline’.

– ‘Officers of the 95th were sensitive to cases which might damage the regiment’s good name’: this point is made by Costello relative to the later flogging of a rifleman named Stratton – it explains however why the many punishments of this kind that he and others like Leach refer to do not appear in the Army’s General Orders.

37 ‘The training at Campo Maior reached a peak on 23 September’: Leach mentions the field day in his MS Journal.

– ‘The tactics taught to the 43rd and 52nd by Moore back in England … were a hybrid of orthodox and rifle ones’: the best evidence of this comes from

A System

of Drill and Manoeuvres As Practised in the 52nd

Light Infantry Regiment

, by Captain John Cross, London, 1823. Cross makes clear that the system described in the book was adopted during the Shorncliffe camp exercises of 1804. The quotation on the 52nd’s method of aiming is from the Cross text.

38 ‘My case was really pitiable, my appetite and hearing gone’: this was not a 95th man, but another sufferer, Sergeant Cooper of the 7th Fusiliers, in his

Rough Notes on Seven Campaigns

, Carlisle, 1869.

38 ‘We were ordered to sit up with the sick in our turns’: William Green.

– ‘Dozens died in the 95th, with O’Hare’s company, for example, losing twelve soldiers’: this comes from the pay and muster roll research conducted by Eileen Hathaway and myself.