Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (60 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

That 1975 news clipping, now yellowed, is still in my files, and I’ve never come across it without a twitch of regret always superseded by a twinge of hope I might yet bike the rails across America, whether or not I ever wrote about it. I understand now — as I didn’t before — the journey would have to be done in total trespass; but then, by law, a tortfeasor takes his victims as he finds them.

I set these words before you, valued reader (a number of you making possible that escape from academia, for which I give you deepest thanks), as preface to another photograph, one I saw not long ago, of a man pedaling a bicycle atop a railroad in the Nevada desert. The picture stopped me, allow me to say, in my tracks. I wrote a letter to the rider, and he soon responded with an invitation to see his Railcycle in operation. His name was Richard Smart, and he was a dentist in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. He suggested we meet a little farther south near a scenic, abandoned line running from the Clearwater River up toward the crest of the Bitterroot Range. When we spoke on the phone to confirm plans, the last thing he asked was, “Are you afraid of heights?” Because we were talking about an old logging railroad, I said no; after all, how high in the air can a hundred-ton locomotive get?

Q and I met him and his longtime fellow biker of the rails, Kenneth Wright, on the western slope of the Clearwater Mountains just outside Orofino and at the edge of the Nez Percé Reservation. Our plan for the next morning was to haul four Railcycles of Smart’s design up along the Camas Prairie Railroad which followed Orofino Creek descending from the western reaches of the Bitterroots. The line, once used for carrying out virgin white-pine, had recently been removed from service and, within a week, the question of pulling up its steel and sleepers for salvage was to be answered. We might be the last people ever to ride those miles.

That evening, Q and I joined the two men for supper at a Mexican café in Orofino, a tiny county seat in a narrow valley opening to the Clearwater River nearly where the Lewis and Clark Expedition on its westbound leg stopped for twelve days to recover from gastro-intestinal discomforts possibly brought on by a diet heavily laced with camas tubers which, nonetheless, had kept starvation at bay during the harrowing trek through the Bitterroots. In his inimitably solecistic and perfunctory style, Clark wrote in his logbook:

Indians caught Sammon & Sold us, 2 Chiefs & thir families came & camped near us, Several men bad, Capt Lewis Sick I gave Pukes Salts &c. to Several, I am a little unwell. hot day.

While the men recovered, they hewed out with hand axes too small for the task several dugouts to carry them onward to the Pacific. Boats, locomotives, Railcycles — transport was all around us.

Railcycle

is a name coined by Richard Smart to describe specifically one of the ten models he had made over the preceding three decades.

Railbike

is the generic term, although in the mid-nineteenth century such a vehicle was usually a velocipede; but even earlier, that older word denoted a two- or three-wheeled cycle, sans pedals, the rider pushed forward with his feet.

It was an antique photograph of a railroad velocipede Smart happened upon in a public-library book that started him on a changed life of pedaling atop tracks on three continents. Although the pictures were different, as were our lives, we shared the experience of a single photo of a two-wheeled, rail-riding contraption that propelled us into an altered life. Coincidentally (I assume), a half continent apart, we’d come upon the images at nearly the same time and at a similar age. Hearing his stories of railbiking was like listening to a book I never wrote.

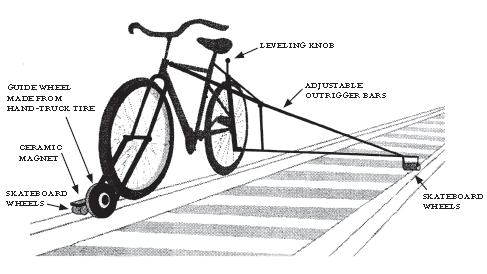

The photograph that set him forth was of a stout man in a baggy suit and vest strung with a watch fob, wearing a black fedora and standing by a bicycle attached to an outrigger connected to a steel wheel the size of a pie plate. Hanging from the handlebars was what looked like a lunch pail, and behind him were a water tank, a steaming locomotive ready to move, and six workers, one of whom might be mocking the rider. The man could have been a track inspector, although some early trains also carried in the baggage car such a velocipede the conductor could ride for help in case of a breakdown out in some to-hell-and-gone. In its fundamentals, the machine reflected the Railcycles we would ride the next day. Dick said, “When I saw the picture of that contraption, I wanted to ride it so bad I could taste it. But you just don’t go out and buy one. I knew I’d have to make my own. That was thirty years ago.”

He started with a standard, wide-tire American bicycle and began experimenting and tinkering with outriggers and guidance wheels to keep the bike atop the rail. His first model used a steel rim from a small boat-trailer, a wheel not unlike the one in the old photograph. Smart had no special mechanical training, unless you consider making a dental bridge mechanical. He did not then — or when we met him — know how to weld. “Persistence is the key to discovering what works,” he said. “With inventing, things get complex before they get simpler because a lot of little inventions go to make up bigger ones.” He paused. “And I have to say, there are a million Americans more mechanical than I am, but I’m the one who wanted the patent so much I wouldn’t give up.”

A basic Railcycle.

In the large, pine-studded backyard of his home on the west edge of Coeur d’Alene, Smart built a small train precisely modeled on the Little Engine That Could. His version, of course, was pedal-powered and just large enough to carry in its coach or caboose his children or those of neighbors around a four-hundred-foot wooden track, through a covered bridge, and across a trestle over a swale. A close look at its construction revealed parts made from a salad bowl, pizza platter, pie tin, flowerpot, wastebasket — all of it assembled with simple hand tools. “The Little Engine That Could, that’s who I am,” he said. “I always think I can. Not to mention at heart, I’m a sixty-year-old twelve-year-old, and for that I thank my mother. She was an elementary-school teacher who taught us to play.”

Smart is an ectomorphic six-footer, fair-haired and blue-eyed, quiet-spoken, kindly, generous, and fascinated by hoboes, at least one of whom he has befriended with free dental care. Over the thirty years of designing and building his Railcycles, he had ridden them almost forty-thousand miles on seldom-used or dormant or abandoned tracks to become the leading proponent of what he once called “America’s slowest-growing sport.” On the eve of our ride, he wondered whether it had become America’s fastest-disappearing sport. The steel and ties and bridges, often formerly left in place after rail abandonment, had come to have too much salvage value to be ignored. Dick said, “Our happiness is two rusty ribbons of steel, but they’re becoming ever harder to find.”

Ken Wright added, “They’ve torn up our playground, and these days we have to drive three hours or more to reach out-of-service tracks. I saw figures several years ago that there are more than forty-thousand miles of abandoned trackage in America, but I think that number is diminishing. The big railroad abandonments of a few years ago are about over. And today, even if the steel isn’t salvaged, thieves sometimes tear out ties to sell to landscapers.”

There was also the life span of dormant tracks: it doesn’t take long for nature to reclaim a grade with saplings and heavy brush and fallen trees that thwart passage. Smart carries a small bucksaw to administer short-lived maintenance. Bridges can be more of a challenge: he and Wright have crossed over creeks on tracks lacking an understructure, the rails drooping as if melting. In such an instance, his Railcycle has an advantage over many other versions in that Smart’s machines quickly convert for road travel or getting around impassable sections of tracks.

The doctor had a collection of photographs he’d taken of wildlife frequently failing to hear his approach: unlike footfalls, rubber tires on steel rails allow silent movement. When animals did notice the man-machine, they seemed not to recognize it as a threat; on sun-warmed ballast, he’d come upon dozing coyote pups, sitting bears, and even rattlesnakes coiling to strike at his front tire.

Wright said, “The farther we get toward our favorite goal of reaching the end of steel, the more wildlife we encounter — things you’re not likely to see from a car or on foot.” For one expedition, the men hired a bush pilot to fly them deep into remote British Columbia to a rail terminus. Not sure they could get through to a highway far down-country, they nonetheless pedaled off on the defunct line, camping as they went. After eleven days and 250 miles, they came out again. “I always want to see the world where nobody else goes,” Dick said. “And I’m always after serenity and beauty.”

Ken Wright was a newly retired professor of chemistry and environmental science and, like his friend, a student of American railroad history. He met Dick when he went to him for dental work and noticed train artifacts in the office. Smart, who connected affably with his patients, told Ken about Railcycles rolling along ghost railroads. “I saw right off all the places we could go,” Ken said. “Another world, one hidden away.” For the last twenty-five years, the pair had traveled together over some fifteen-thousand miles of ghost lines. Dick said, “If we’re away too long from the smell of creosote, we get withdrawal symptoms. It’s a good escape from a high-stress profession.”

The men called each other “Boss,” and Wright said, “The car wash, Boss.” Dick smiled. “Dentistry is like building a ship in a bottle while standing in a car wash,” he said. Ken prodded again: “The abscess.” To that, Smart frowned. “People will put off going to see a dentist. A patient came in with an abscess he’d let go way too long. When he opened his mouth, the muscular strain caused it to burst all over me. That kind of foul vomica is unpleasant in all ways.” Far more so, he meant, than a broken railbike miles from assistance.

Dick was a believer in the HPV movement — human-powered vehicles — and as such he pedaled to work in a peculiar, three-wheeled, futuristic-looking machine that enclosed him inside a fiberglass and carbon-fiber canopy with a windshield and a wiper, a headlight and air scoops; on the interior (not for claustrophobes) were a stereo and deep-cushion seat. More than once, somebody watching him raise the pod and climb out had asked, “Where’s the mother ship?” He bought the velomobile from Leitra, a company in Denmark where human-powered vehicles receive serious consideration. The thing looked like the front end of a light plane that had lost its wings, or — from another angle — a daisy-yellow, streamlined, high-top hiking shoe with spoke wheels. It had twenty-one gears, weighed seventy pounds, and on a downslope Dick could reach almost fifty miles an hour. He said, “It stops at a gas station only for the air hose.”

Roads, rails, I said, you’ve got the types of travel covered except for hulls and wings. Ken smiled; he knew what was coming. Dick said, “I’ve read that a few months after the Wright brothers first got off the ground in North Carolina, an Idaho man up this way invented a pedal-powered biplane. I haven’t pedaled aloft yet, but I do have a pedal-powered canoe. I pull it on a little trailer behind one of my bicycles and take it out on Lake Coeur d’Alene. A small propeller drives it along at a pretty good clip, especially into the wind. It has a rudder I control with bicycle handlebars.” Q said, “A canoo-cycle.”

Then she asked how people react when they encounter him with one of his HPVs. “Oh,” he said, “I think there’s a third who don’t even see me. Then there’s a third who write me off as Doctor Gyro Gearloose. But the last third — they want to join in.”

That final group Smart tried to reach in the 1980s with Railcycles in three models he assembled and sold, all made from standard mountain bikes. For a while he also offered twelve sheets of plans showing how to build a Railcycle. He wrote a newsletter and approached anyone able to advance preservation of abandoned tracks or assist in opening seldom-used lines for occasional railbiking. To all who would listen, he pointed out how a rider was safer on a dormant or even infrequently used railroad free of fast-moving autos and trucks driven by drunks or of late, cell-phone inattentives.

For a while, he said, “I was married to the idea, and sometimes it was tricky balancing dentistry and a family with four children. But Ann, she’s a wife who helped me pursue my passion even when it was hard on her. I used to connect Railcycles so all of us could ride together, and once I hooked up six to see if it could be done. It could, and one person could easily pull all of them.”

In 1980, four years after his first Railcycle,

Sports Illustrated

published a short piece about the bike, and much publicity followed, although most of it was small notices (“Ripley’s Believe It or Not!”). Dick wondered briefly whether he could afford to give up dentistry. His company — and even more his advocacy — drew the attention of a few railroad corporations that chose to believe he was urging people to ride active rail lines, “live steel.” One morning Dick came into his dental office to find a railroad detective waiting to talk to him, and not about an abscessed tooth. “Evil letters” began arriving from rail executives, but among them was one concluding politely: