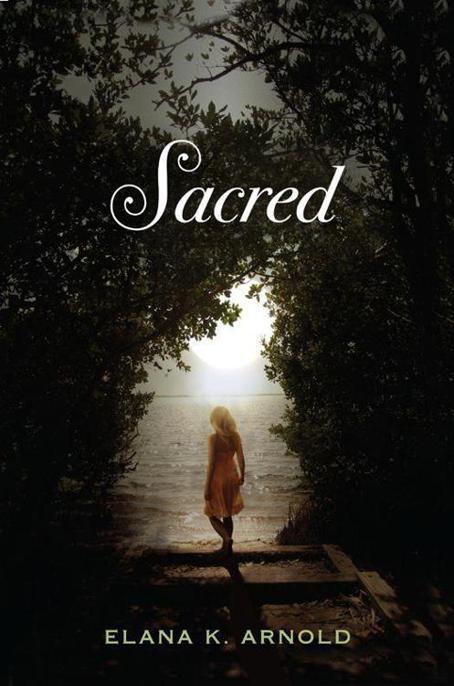

Sacred

Authors: Elana K. Arnold

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Love & Romance, #Religious, #Jewish, #Social Issues, #Emotions & Feelings

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by Elana K. Arnold

Jacket photograph copyright © 2012 by Terry Bidgood/Trevillion Images (background) and Illina Simeonova/Trevillion Images (girl)

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Arnold, Elana K.

Sacred / Elana K. Arnold. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Since her older brother died Scarlett has felt emotionally cut off from everyone on Catalina Island except for her horse, and she has become anorexic—but when she meets a strange boy named Will Cohen she begins to rediscover herself.

eISBN: 978-0-307-97414-3

1. Grief—Juvenile fiction. 2. Loss (Psychology)—Juvenile fiction. 3. Anorexia—Juvenile fiction. 4. Santa Catalina Island (Calif.)—Juvenile fiction. [1. Grief—Fiction. 2. Loss (Psychology)—Fiction. 3. Anorexia—Fiction. 4. Love—Fiction. 5. Santa Catalina Island (Calif.)—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.A73517Sac 2013

813.6—dc23 2012010891

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For my Nana

,

WHO TELLS THE BEST STORIES

Contents

Eleven: The House Behind the Hill

Nineteen: Two Roses for Scarlett

Can you understand? Someone, somewhere, can you understand me a little, love me a little? For all my despair, for all my ideals, for all that—I love life. But it is hard, and I have so much—so very much to learn.

—

S

ylvia Plath

I am supposed to be having the time of my life.

—

S

ylvia Plath,

The Bell Jar

ONE

A

ll around me, the island prepared to die. August was ending, so summer had come, bloomed, and waned. The tall, dry grass on the trail through the hills cracked under my mare’s hooves as we wound our way up toward the island’s heart.

Summer sun had bleached the grass the same blond as my hair, which was pulled into a rough ponytail at the nape of my neck. The straw cowboy hat I always wore when I rode was worn out too, beginning to split and fray along the seams.

The economy had done its part over the past few years to choke the life out of the small island I called home—Catalina, a little over twenty miles off the coast of Los Angeles. This summer, the island had felt remarkably more comfortable, as the mainland’s tourists had largely stayed away. But even though it was nice to have some breathing room for

a change, it came at a price. Our main town, Avalon, had seen the closure of two restaurants and a hotel, and my parents’ bed-and-breakfast had gone whole weeks without any guests.

It was selfish that I enjoyed the solitude. Selfish and wrong, but undeniably true—solitude was a luxury, a rare commodity on a twenty-two-mile-long island that I shared with three-thousand-plus people, all of whom seemed to look at me differently lately, now that my brother was dead.

Yes, death was all around. The dry, hot air of August pressed down on me, my brother would not be coming home, and Avalon seemed to be folding in on itself under the weight of the recession, like a butterfly that’s dried up, its papery wings faded.

As if she could sense my mood, my mare, Delilah, tossed her pretty head and pulled at her bit, yearning to run. Delilah was also a luxury, one my parents had been in the habit of reminding me we really couldn’t afford—until Ronny died. Then, suddenly, they didn’t say much to me at all.

I get it, your kids are supposed to outlive you, it’s the natural order of things, but since Ronny had died, it was like I was dead too.

That was how I measured time now. There were the things that happened Before Ronny Died, and then there was Since Ronny Died. It was as sure a division of Before and After to our family as the birth of Jesus is to Christians.

Before Ronny Died, Mom smiled. Before Ronny Died, Daddy made plans for expanding our family B&B. Before

Ronny Died, I was popular … as popular as you can be in a class of sixty-four students.

That was all different now. Since Ronny Died, my mother didn’t seem to notice that a film of dust coated all the knick-knacks in the front room. My dad didn’t weed the flower beds. More than a tanking economy was sinking our family business. We were bringing it down just as surely, our gloomy faces unable to animate into real smiles. We probably scared off the guests.

Ronny died last May in the middle of a soccer game. Cause of death: grade 6 cerebral aneurysm. He was just finishing up his freshman year at UCLA. We weren’t with him. The distance between Catalina Island and the mainland seems a lot farther than twenty miles when your brother’s body is waiting for you on the other side.

I blinked hard to clear these thoughts. They would stay with me anyway, I knew, but I let Delilah have her head, knowing from experience that while we were galloping, at least, my mind would feel empty.

My mare didn’t let me down. Twitching her tail with excitement, Delilah broke into a gallop, her short Arabian’s stride lengthening as she gathered speed, her head pushed out as if to smell the wind, her wide nostrils flaring. Her coat gleamed red in the afternoon sun.

Ronny used to joke that

Delilah

should have been named Scarlett, not me. Ronny was a literal kind of guy. And he liked to say that

I

should be called Delilah, because of my long hair. That was stupid, of course; in the Bible, Delilah wasn’t the one with the long hair. It was her lover, Samson,

whom she betrayed by chopping off his hair—the source of his strength—while he slept, damning him to death at the hands of the Philistines.

Ronny just shrugged when I explained all this to him. Sometimes he could be awfully dumb, for such a smart guy.

I wanted to cut off my hair after Ronny died. I stood in the kitchen the afternoon of the funeral, dressed in one of my mother’s suits left over from her days as a lawyer, back before she and Daddy decided to move to the island to open a B&B. In my hands, I held a long serrated knife. There was a perfectly good reason for this: I couldn’t find the scissors.

But when my mother came into the kitchen, fresh from burying her only son, and saw me standing in the kitchen with a knife in my hand, she freaked out. She started screaming, loud, piercing screams, as if I were an intruder, as if I planned to use that knife against her. Or maybe she thought I was planning to use it against myself, pressing the blade into flesh instead of hair. Then Daddy ran in and saw me there, and his eyes filled with tears, something I’d seen more times that week than I’d seen in the sixteen years of my life up till that point. He took the knife gently from my hand before leading my mother to bed.

Afterward, I couldn’t seem to gather the strength to cut my hair. I had wanted to cut it because Ronny had loved it, though he’d never have admitted as much. He used to braid it while we watched TV. I wanted to cut it off and then burn it.

But my mother’s expression had taken all the momentum out of my plans. So as I rode Delilah through the open meadow at the heart of the island, I felt the heavy slap of my ponytail against my back, hanging like a body from a noose in the elastic band that ensnared it.

Delilah tossed her mane and slowed to a trot, heading for a clump of grass at the base of a large tree. I thumped her neck with my palm.

“Good girl,” I murmured as her trot became a slow, stretchy walk. I slid down her side and pulled the reins from her neck. She made a contented sound as she began pulling up bites of grass. I flopped down next to her in the tree’s shade, her reins looped loosely over my wrist, and allowed my body to relax.

School would be starting soon. Junior year. This was supposed to be the best year of high school, even if the academic load would be tough: too soon to worry about college applications, and since I was no longer an underclassman, all the required PE classes were behind me. Still, I was dreading it. Just a few more days, and then I’d be yoked to school as surely as Delilah was yoked to me.

I tried to remind myself of the good things that went along with school in a halfhearted effort to cheer myself up. Lily would be back; that would be good.

My best friend, Lily Adams, was a member of the small wealthy class on Catalina Island. Her parents could have lived anywhere they chose. Independently wealthy as a result of some smart real-estate purchases in the early 1990s, they had come to Catalina because they thought it would

be a safe place to raise their kids: Lily and her younger twin brothers, Jasper and Henry.

Catalina was safe, except for the occasional boating accident. The visitors bureau boasted that “violent crimes are virtually nonexistent on this island paradise.” Well, the paradise part was dubious, but as far as I knew, it was true about the lack of crime here.

Because of their money, though, and because their livelihood wasn’t dependent on the high season for tourism like almost everyone else’s on the island, Lily’s family got to travel during the summers. This year they were touring Italy. Her family had offered to bring me along; Jasper and Henry had a built-in friend (or enemy) by virtue of being twins, but Lily’s parents thought it would be nice if I could come to keep Lily company.

That had been the plan, Before Ronny Died. Then, suddenly, my parents couldn’t stomach the thought of my being so far away from them … though they hadn’t seemed to notice me much this summer, and the three of us existed pretty much like strangers living under one roof all season long.

It made me angry that I had missed out on the trip. But I felt rotten that I could be mad at my parents for anything right now … and that I could be mad at Ronny, who was dead, for screwing up my summer plans. Lately I just wasn’t a very good person.

Lily didn’t seem to agree. She’d kept up a stream of communication all summer, through email, Facebook, and text messages, even though I rarely wrote back. She understood;

she didn’t hold my silence against me. I hoped things were going to get better now that she was coming home.

Friday afternoon. She would be in the air, on her way to Los Angeles from Rome. Then she and her family would come to Catalina by helicopter. They were the only people I knew who could afford to travel this way. Most everyone else took the ferry, and a few of the wealthier families kept their own boats for transportation to the mainland, but Lily’s family coptered. Not bad.