Sacred Sierra (39 page)

Authors: Jason Webster

Ibn al-Awam,

Kitab al-Falaha

, The Book of Agriculture, 12th century

FOLLOWING IBN AL-AWAM’S

advice, I got up early this morning to churn up some of the soil around the base of the olive trees. Although I didn’t quite make it for sunrise itself, it was still early in the day and the worst of the heat had yet to make itself felt. Great weeds have built up over the past weeks and months, so it gave me an excuse to take some of those out at the same time. Most of them look like some variety of fennel, great skinny stalks stretching up to around six or seven feet. The green flowery heads give off a pleasant scent when I crush them between my fingers, but digging around in the ground I’ve yet to find nice bulbous bits for eating that I’m used to finding in the markets. Perhaps this is some other kind of variety.

I tried not to dig too deep around the olive trees, for fear of damaging the roots, but a hoe is perfect for this kind of work, angled as it is so that it just scrapes up the top layer of soil. I still marvel sometimes at how versatile this simple, ancient tool can be.

There was plenty of dust, all right, as the ground is becoming increasingly dry again, and I had to break away a couple of times from the cloud I’d created just to be able to breathe properly. Quite what good this is doing to the olives beyond killing any competing weeds I can’t say. Perhaps the dust coating makes them less appetising for the birds, or protects them against disease, or the sun. Anyway, we’ll see next December if it has worked. Already there seem to be far more olives on the trees this year than last. Whether they’ll hold out till harvest time is another matter, though. Last summer a freak hailstorm wiped them out. There’s a saying:

Aguas por San Juan quitan vino, aceite y pan

– If it rains around midsummer, there’ll be no wine, oil or bread. The sun has been shining constantly now for the past three weeks, so at least we’re all right on that score.

If the soil feels so dry, though, it’s not just because of the lack of rain. The downpours of April and May and then a few more into early June drenched the whole area. It’s the intensity of the sun itself, I think, which drains the land of its moisture. Perhaps not the most earth-shattering observation, but being up here you can almost feel the liquids being sucked out by the harsh white light of midday – not only from the soil and plants, but from your skin and body. The flies have made a dramatic comeback, and buzz hyperactively around our mouths in search of a precious drop of moisture. And I can almost sympathise with them while swatting them dead – there’s so little of it up here. The only place in the world where I have come across such fast, death-defying flies was in the Sahara. It makes me realise how vulnerable this landscape is: an annual downpour or two is all that keeps it from turning into desert. Any change for the worse in the weather patterns and in a matter of five to ten years it would be unrecognisable.

Still, with my eyes fixed on no further than next spring, I’ve planted some iris bulbs near the house – perhaps my last gardening act before the autumn, and the new farmer’s year. I was surprised when Arcadio told me a couple of months back that now was a good moment to plant

them

– I would have thought November would have been a better time, and that’s certainly what it says on the packet. But I’ve come to trust him. If he says summer is better, then a summer planting it shall be. Once I’d buried them in the soil, I gave the bulbs a thorough, late evening watering, with sharp mental images of them brightening up the hillside next spring.

*

I hadn’t seen Arcadio for a while: I knew he’d been called some time around now for his operation as part of the national rush to get things ‘done’ before the great August holiday, when almost everything – including hospitals, it seems – either closes down or works part-time. I looked out a few times to see if his green Land Rover was heading our way from further down the valley, but there was no sign of him. I would have heard, I thought, if something had happened. It was a simple operation, and, although I knew he was frightened, there was surely nothing that could go wrong.

The days passed, though, and still he didn’t show up. Eventually I decided to pop over on my way down to the village one day. Although I knew where he lived, he had always been the one to come up and see me: it was a strange experience going to his house.

Arcadio had a

mas

among a group of other houses just off the road, near the bank of the river. A small, old dog was sitting by the door when I drove up, barely raising its head as I walked over and parted the chain curtain to knock on the door. A few plants lined the whitewashed steps, and fresh light-blue paint had been brushed around the doorway and windows in the traditional fashion.

There was a long pause, and I was about to walk away, assuming no one was there, when I heard movements inside. Finally, the door was opened and there stood Arcadio.

‘

Home

,’ he said with a smile when he saw me. He looked tired, and his slippered feet shuffled along the floor as I followed him into the house.

The room was dark and bare, a cold, tiled floor and unadorned walls. He sat down next to a small round table with a lace cloth covered by a glass top and pointed for me to pull up a chair. A jug of water stood next to a vase with some drying herbs stuck in it.

‘

M’han deixat fet pols

,’ he said. ‘They’ve screwed me up.’

The shutters were down on the only window: it kept the heat out, but it felt miserable. I wondered if he’d been told to protect his eyes from the sunlight as they recovered from the operation.

‘What happened?’ I said.

‘Ah, the operation went fine,’ he said. ‘Took out the cataracts. I was only in there for half an hour.’

He got up and shuffled to the kitchen, where he opened the fridge, took out a bottle of cold wine and poured a glass for me.

‘Not having one yourself?’ I asked. He shook his head.

I tried to look in his eyes to see if there was any noticeable difference from before, but in the poor light it was almost impossible to see.

‘So your eye’s better now?’ I asked.

He chuckled. ‘That’s the problem. I can see too well.’

He scratched the side of his nose and laid his hand out on the table.

‘Can’t drive any more,’ he said. ‘

Me dona por

– I’m frightened.’

For years the cataracts had been growing slowly in his eyes, and he had simply grown used to them, driving up and down the same old tracks and roads as he had done for so many years. He knew this valley better than anyone. He didn’t need eyes to be able to move around. But now that they’d been given back to him, the acuteness of this new-found sense had thrown him. He couldn’t drive up the valley any more: it was too dangerous.

‘That bend past the turning to the watermill,’ he said, ‘where there’s a long steep drop on the other side …’ He waved his hand in the air to signify how frightening he found it now.

‘Must have driven along there thousands of times,’ he said. ‘Don’t remember it being like that. I tried to do it a week or so ago and had to turn back.’

That in itself must have been a hair-raising experience: there was virtually no room to make a U-turn there.

‘Almost makes me want to go to the hospital and ask for my cataracts back,’ he said pouring himself some water.

I offered to come down and pick him up myself. It was tragic that by giving him back his sight he should have been left off worse than he was before. What would he do if he couldn’t carry on with his everyday

routines

? The mountains didn’t feel the same without him pottering around pruning his almond trees, inspecting his beehives, and keeping an eye on things. But he refused.

‘My daughter’s on at me again to move into the village. Says I’m getting old and she can’t look after me properly if I stay out here.’

He paused for a moment and looked towards the door, as though expecting someone to arrive any minute.

‘Don’t like the village,’ he said. ‘Too many people.’

From his body language, though, it seemed that for the first time he might actually be contemplating the move he had been fighting. In the past the

masovers

used often to move into the village in old age to live out their last years in some degree of comfort after a lifetime struggling just to survive in the harsh

mas

environment. But now there was a proper tarmac road linking Arcadio’s house to the village; he had electricity, running water, a mobile phone. The only other thing he needed was some degree of autonomy and the ability to get around to check on all his fields and scattered pieces of land around the valley. But that was slipping away from him. It was the first time he’d come into contact with modern medicine. It had given him back his sight, but had taken something vital away from him at the same time.

‘I’d have to sell the Land Rover,’ he said almost under his breath. Then he raised his eyebrows a little and looked at me. ‘Interested?’

*

We were woken up this morning by the sound of something alive scrabbling around inside the house. As I drifted into wakefulness, it became it clear it wasn’t a mouse – the sound was too loud – and that whatever it was was desperately trying to get out again. Salud got up first and went to check and told me it was coming from the fireplace. We have a black iron stove there: it seemed a bird had flown down the chimney and got stuck there, where the flue joined the casing. After much heaving and pulling I finally managed to open it up to let the poor thing out. At first nothing happened, then with a great flapping of wings, the blackened bird came flying out, dashing itself against the doors and windows of the kitchen. It looked like some kind of harpy, its claws outstretched, its eyes bright yellow against the unnatural tone its feathers had adopted from the soot inside the chimney. It flew so fast

and

frantically I couldn’t see what kind it was: perhaps a thrush. Eventually, though, we managed to herd it towards one of the open windows and it flew away. I only hope it can clean itself and survive.

Living on our own up here, with so much contact with a natural – and sometimes supernatural – world, these things start to feel like omens.

*

Jordi rang up to say that a large box had arrived for me and was taking up space inside his tiny office. I drove down to the village and found him glum-faced, sweat patches spreading from under his arms as he sorted the mail.

‘Air conditioning’s packed up again,’ he said. ‘And the holidays are coming.’

Surely, I thought, that was something to look forward to, particularly for one so workshy.

‘What am I supposed to do over the whole of August?’ he said, pleading. ‘I need something to keep me busy. Can’t just sit on the beach the whole time.’

‘Why don’t you come back up to the village,’ I suggested, ‘and do some moonlighting. Taking the post out to the

masos

so we don’t have to drive into the village, for example.’

‘Can’t do that,’ he said. ‘Years of strikes and workers’ blood went into winning us our annual holiday.’

I unburdened him of my package and took it eagerly back to the farm. I had been waiting for this to arrive for over a week.

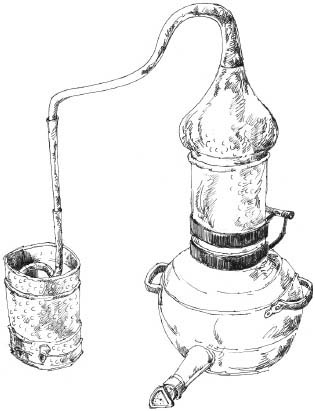

I opened the box: inside was a brand new bright copper still. With its bulbous form and curiously shaped lid, it looked like the dome of a Persian mosque, or Russian Orthodox church. I lifted it out and placed it on the table. It was a thing of beauty, wonderfully crafted, with little brass handles. For a few moments I simply stroked it, following the smooth contours with my fingertips. It was impressive enough just to sit as an ornament on some shelf or windowsill. But it was also fairly large, and was clearly meant to be used. Salud wanted me to make some essential oils using the herbs from the mountainside, but I was more tempted by the thought of employing it to make some mind-numbing and preferably illegal hooch. For a man with his own mountain, and

now

a still, there were no limits. It was time to think big. Perhaps we could even start a business – use fresh water from the spring, rosemary and thyme for a bit of flavour, all natural ingredients. People would buy it in bucket loads. Organic Mountain Moonshine. Acquavita de España. Webster’s Weed Killer. Possible names for the potion I was going to make had already started to form in the back of my mind.

But first I was actually going to have to produce something. The instructions that came with the still were basic, so I had to fish around for other sources of information on how to use it. I remembered a few experiments as a thirteen-year-old in the chemistry lab at school – in fact, probably the only thing I

did

remember from those classes. The whole process had been dressed up as a means of testing the different evaporation points of alcohol and water, but in reality was an excuse for our curiously small chemistry teacher to stock up on his supply of booze for the next end-of-term party. Along with the obligatory admonitions that what we were performing was against the law, we’d make pints of

the

stuff for him, only to see him siphon it off and place it in the locked cupboard at the back of the class ‘for disposing of later’.