Sacred Sierra (7 page)

Authors: Jason Webster

After watching for a time, the teenagers beside me were now preparing to climb down the scaffold to get inside the square themselves.

‘What do you think of the bull?’ I asked them as they started swinging their legs over the top.

‘Watch him on the right,’ the eldest one said. ‘He pulls round quickly to the right once he’s finished his charge.’

My legs didn’t move, frozen. I watched as the boys descended.

The bull tossed and whipped its head from side to side as they leapt into the square and started to run in parallel towards the other side. The flames were sickeningly close to their exposed skin and I stared, not wanting to see, as the elder boy pushed away at the fire with the T-shirt

in

his hand. With a ducking motion he was quickly inside the cage and safe, but I saw him hold up the cloth to his friends: it was smoking; they laughed. The man with the beer gut, however, was standing on his own in a corner of the square, egging the bull on with loud, hoarse shouts, to come and charge at him. It seemed suicidal. For a long while the bull ignored him, more preoccupied with the swift, eye-catching movement of the youths than the heavy ranting of the older man behind. But a lull came unexpectedly, and in that moment the bull turned swiftly on the spot, pawed at the ground and charged full-speed at him. The space the man had put himself in was virtually a trap, with a wall cutting him off on the left, and only a small gap for him to escape on the right. He stood for a second, arms outstretched as though daring the beast to impale him, and then threw himself in a dive towards his one exit point. But the bull seemed to anticipate him, and as soon as the man was dashing towards the safety of the cages, he pulled his head round, checked his run, and in a flash was beating the man’s bare back with his forehead. The man fell to the floor, the bull scraping with his flaming horns at his prostrate body lying in a pile in the dirt by one of the cages. The light from the torches on the bull’s horns lit up the faces of the villagers inside, their expressions frantic as those closest tried to pull the man’s body towards them. I felt my body go cold, unable to look away.

Some boys from the other cages ran out and tried to draw the bull’s attention away from the man on the floor. For a moment he seemed to ignore them, then with a start lifted his head from his victim and started charging at his new tormentors. No sooner had he moved away than the fat man was on his feet, as though nothing had happened, and was running like a terrified toddler into the nearest cage. I gave a thankful sigh. Miraculously it looked as though he was all right: after a few concerned words from the people around him, he was now back at the front of the cage, shouting abuse at the bull. There didn’t appear to be a scratch on him.

I climbed down the scaffold and walked away from the crowd, my feet scuffing the gritty soil underneath. For a second I looked back, as though searching for a reason for not hanging around and giving it a go. The flames from the bull’s horns were flashing through the silhouettes of the people pressed inside the protective cages. I was glad that this

festival

still seemed to be alive and strong up here, but personally I’d seen enough: the image of the fire-beast had been engraved on my mind for good.

I found Salud chatting to Mariajo, the forty-year-old village punk who ran the grocer’s store. Like the rest of the villagers, Mariajo was virtually legless.

‘Did you have a go?’ Mariajo asked with a smile. I shook my head. ‘You’re better off,’ she said. ‘It’s for young boys and old men, all that. They’re crazy –

bojos

. It’s as if they need to

prove

they’re men. Can’t understand it.’

Salud nodded vigorously.

‘We’ve got plenty of challenges of our own to deal with up on the mountain,’ she said squeezing my arm and leading me away. ‘You don’t want any of that.’

The sound of the crowd and the screams from the bull-running gradually faded as we walked away from the square, an enveloping silence seeming to flow from the narrow, empty houses lining the streets.

‘I’ve been thinking,’ Salud said as we headed towards the car. ‘Living up here on the mountain …’ She paused.

‘If we get through this, if we’re still together in a year’s time,’ she said. ‘Maybe we should … get

married.’

The Story of Mig Cul Cagat

ONCE UPON A

time, in a

mas

not far from here, there lived half a chicken called Mig Cul Cagat. None of the

masovers

knew who he belonged to, as he appeared one day as if from nowhere. But they gave him food and let him live with the rest of the chickens. One day, as he was picking around the

era

, Mig Cul Cagat came across something hard and shiny on the ground. He blew on it and saw that he’d found a coin.

‘Aha!’ he thought as soon as he realised what it was. ‘With this I can go and marry the King’s daughter.’

And without a second’s thought he left the

mas

and set off to the royal palace to seek his fortune.

As he was walking along the road he came across a great ants’ nest, blocking his way.

‘Where are you going, Mig Cul Cagat?’ the ants asked him.

‘I’m off to the palace, to marry the King’s daughter,’ he replied.

‘Only if we let you pass!’ cried the ants.

But Mig Cul Cagat wasn’t going to let them get in his way.

‘Ants!’ he said. ‘Climb up into my backside.’

And as if by magic, all the ants suddenly found themselves inside the half-chicken.

Mig Cul Cagat carried along his way, until he came across a big hammer.

‘Where are you going, Mig Cul Cagat?’ asked the hammer.

‘I’m off to marry the King’s daughter,’ he replied.

‘Only if I let you pass!’ said the hammer.

But Mig Cul Cagat simply said: ‘Hammer, get into my backside.’

And so it did.

Mig Cul Cagat carried along the road, and soon he was getting close to the capital city, and the home of the King. But in order to get there he had to cross a river.

‘Where are you going, Mig Cul Cagat?’ asked the river.

‘I’m going to the palace to marry the King’s daughter,’ he replied.

‘Only if I let you pass!’ said the river.

And Mig Cul Cagat said: ‘River, climb up into my backside.’ And the river disappeared inside him and he walked across and into the city.

Now when he reached the King’s palace he knocked on the door and a guard appeared.

‘Where are you going, Mig Cul Cagat?’ he asked.

‘I’m going to marry the King’s daughter,’ Mig Cul Cagat replied.

The guard went to tell the King. But the King just laughed and ordered that the half-chicken be thrown in jail for his insolence. And he had a vast amount of food placed in the dungeon with him.

‘You can only have my daughter if you can eat all that food before dawn,’ the King said.

When the King and guard had both gone, the chicken called to the ants.

‘O ants! Come out, come out. There’s work to do.’

And the ants climbed out of his backside and Mig Cul Cagat told them what had happened.

‘Don’t worry,’ said the ants. ‘We’ll fix it.’

And they set about eating all the food that had been put in the dungeon, and by morning it had all gone.

The King was furious when the guard told him the news.

‘You can only marry my daughter,’ he cried, ‘if you break out of the dungeon.’

But when he had gone, Mig Cul Cagat called out: ‘O hammer! Come out, come out. There’s work to do.’

And the hammer came out of his backside and Mig Cul Cagat told him what had happened. So the hammer started bashing the dungeon door, and within a few moments had broken it down and Mig Cul Cagat was able to walk free.

Now the King saw the half-chicken walking around the yard, and decided to finish him off once and for all. He ordered the guard to grab Mig Cul Cagat, saying: ‘Light a fire. We’re going to use this chicken to make a paella!’

So they tied Mig Cul Cagat down and they placed him in a huge paella pan on top of a burning fire.

But Mig Cul Cagat called out: ‘O river! Come out, come out. There’s work to do.’

And the river came out of his backside and doused the flames and saved him.

By now the King realised there was nothing he could do, and so he finally allowed Mig Cul Cagat to marry the princess. The wedding was held straightaway, and all the ladies of court cried tears of sadness as they saw the newly-wed princess walking back down the aisle with half a chicken as her groom.

That night, when the couple retired to their bedchamber, the princess started stroking Mig Cul Cagat, for although she had hoped for a better husband, she was not unkind. But as her fingers passed through his feathers she felt something unusual. Looking closer she saw that it was the end of a needle, a needle of gold. Mig Cul Cagat said nothing, and so she pulled at it and suddenly there was a bang. A bright blue flame filled the room, and where there had once been half a chicken, there now stood the handsomest young man. The princess gave a cry.

‘Do not fear,’ said the young man. ‘For I am in fact a prince, and you have broken the charm that was placed on me. And I am still your husband, if you will have me.’

The princess fell in love and threw herself into the prince’s arms.

And they lived happily ever after.

OCTOBER

October,

as it is called in Latin, is known as

Tishrin al-Awal

in Syriac and is the first month of the year for the Syrians; the Persians call it

Abanmah.

In this month the cold grows stronger and sheep, which are now full with milk, suckle their young. This is the time for gathering fennel seeds, anis, onions, saffron, violets and pistachios. Green olives for pickling are also harvested now, before they become full of oil and start turning yellow. It is said that wood cut after the third of this month will not become infested with woodworm

.

Ibn al-Awam,

Kitab al-Falaha

, The Book of Agriculture, 12th century

OCTOBER CAME, LIKE

a new spring after the half-life of summer. The hillside was awash with colour as the gorse bushes burst into bright yellow bloom, quickly followed by the pale blue of the rosemary flowers and the deep mauve of the

bruc

, a kind of heather. The birdsong seemed to grow louder and last longer through the day rather than passing a lull and silence during the hottest hours. But still, although it was usually one of the wettest months, it refused to rain. Pale blue skies stretched endlessly out over the valley, the temperatures regularly reaching the mid-twenties in the afternoon. The oak by the house, one of the few deciduous trees on our land, refused point blank to give any sign that autumn was in the air, its leaves lush and green as though it were the beginning of May. Pleasant though it was, there was something abnormal about it, as though by taking so much time the change in season was coiling itself like a spring: when it finally came it would be let off like a gun.

The new flowers had brought an influx of bees. Salud, never happy

with

insects of any kind, was frantic at the invasion but I was fascinated by them, watching as they buzzed around the garden and darted in and out of the house through the open windows. They were honeybees, I was certain, which meant that not far from us there must be some hives. Sorting through some of the wreckage of the other

masos

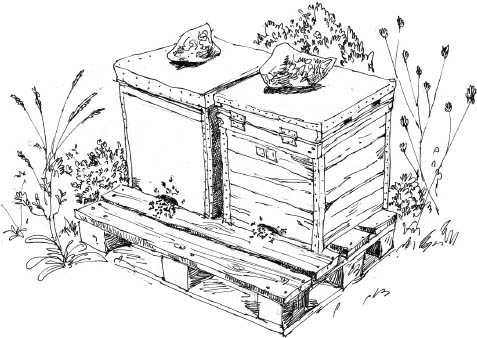

nearby I’d come across one item that looked very much like an old hive of some sort: pieces of thick cork bark tied together to form a kind of cylinder. It was bent out of shape now, but if I was right about what it was, it suggested beekeeping had been a traditional activity up here.

I couldn’t remember how far bees would fly to collect nectar, but it couldn’t be more than a few miles. One clue came from the way the bees would always get stuck on the east window – one we rarely opened – when they entered the kitchen. It was as if they knew that ‘east’ meant home. Wherever the hives were, I reasoned, they must be in that direction.

One afternoon I decided to go down and investigate, heading over the terrace fields and towards the dirt track that led to Arcadio’s almond groves. It was another hot day and I was wearing just an old pair of holey jeans and a T-shirt. A straw hat kept the worst of the sun’s intense rays from the top of my head.

Strips of plastic were hanging mysteriously from the almond trees when I reached Arcadio’s fields, but there was no sign of any beehives. However, I noticed that the sound of the bees, that wonderful background hum of life and energy, was several decibels higher than up at the house. The almonds weren’t in bloom, so it seemed I might be on the right track.

I carried on, pushing my way through the grass, trying to let the sound of the bees itself lead me to their hives. Finally I caught sight of something above my head. I walked up to the terrace wall and stood on tiptoe: there in front of me were at least fifty beehives, wooden boxes painted grey, with thousands upon thousands of bees hurrying in and out of tiny holes at the base of each one. My eyes widened as two thoughts simultaneously crossed my mind: firstly of the enormous amount of honey that must be produced right here under our noses; and secondly that I mustn’t breathe a word of this to Salud. It was bad enough with all the spiders, wasps and sundry beetles and flying bugs

that

disturbed her up here in the mountains; if she discovered the presence of a vast bee colony this close she might leave and never come back.