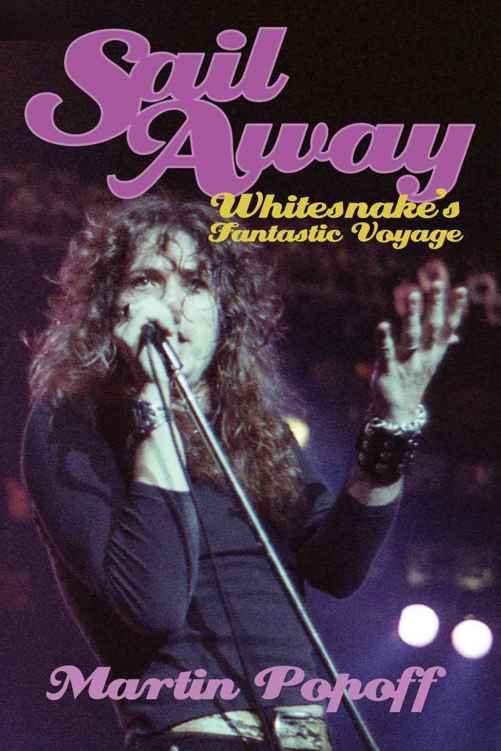

Sail Away: Whitesnake's Fantastic Voyage

Read Sail Away: Whitesnake's Fantastic Voyage Online

Authors: Martin Popoff

First published

in Great Britain in 2015 by Soundcheck Books LLP, 88 Northchurch Road, London,

N1 3NY.

Copyright ©

Martin Popoff 2015

ISBN:

978-0-99-294806-1

All rights

reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or

by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or

any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from

the publisher.

This book is

sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise,

be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is

published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent

purchaser.

Every effort

has been made to contact copyright holders of photographic and other resource

material used in this book. Some were unreachable. If they contact the

publishers we will endeavour to credit them in reprints and future editions.

This title

has not been prepared, approved or licenced by the management, or past or

present members of Whitesnake or David Coverdale and is an unofficial book.

A CIP record

for this book is available from the British Library

Book design:

Benn Linfield (

www.bennlinfield.com

)

Contents

1.

Early Years – “The Unrighteous Brothers”

2

White Snake

/

Northwinds

– “I’m Not Sure

You’re The Right Bass Player To Play With Cozy”

3.

David Coverdale’s Snakebite – “A Particular Creative

Umbrella”

4.

Trouble

– “The Room Literally Shook”

5

.

Lovehunter

– “It’s Not Shakespeare”

6

.

Ready

An’ Willing

/

Live... In The Heart Of The City

– “I’ve Seen Paice

Reduce Grown Men Drummers To Tears.”

7.

Come An’ Get It

– “How’s That For A Double

Name-Drop?”

8.

Saints & Sinners

– “Are You Thinking It As

Well?”

9.

Slide It In

– “You’ve Got To Get Rid Of The Old

Guys”

10.

Whitesnake

– “There Were 30 Something Tracks Of

Guitars”

11

Slip Of The Tongue

– “We Made More Money Than God

On The Last Record! “

Introduction

Those who know me, will know that the

web of intrigue that is the Deep Purple family has occupied much of my writing

time. I have somehow managed to hatch a book on Rainbow, one on Dio, two Sabs

and four on Deep Purple themselves. Perhaps after this, there’s only a Gillan

book to come (my second favourite band ever after Max Webster), to round off

the significant bits of the family tree. No, I will not be penning a Paice

Ashton Lord volume, neither a treatise on the jazz fusion of the preposterous

Ian Gillan Band, or a tiny tome on Elf (yes, readers periodically ask me for

that one).

But I digress. Whitesnake, ah yes. A joy

to pen, this has been for three main reasons: firstly, how comfortable it is to

talk to the players in this drama (Bernie Marsden being of particular note, a

man legend that I hopefully can class as something more than an acquaintance at

this point); secondly, Neil Murray plus some of the later actors such as John

Kalodner, the very funny Keith Olsen, an always gracious Rudy Sarzo; lastly,

but not leastly, David Coverdale himself – ever the charmer.

As well, I was propelled by the

facts of the case, the complicated tale as David evolved from Purple through

wobbly solo years to the Mk.1 version of the band (I’m really only going to use

two Mk.s!). Then it gets rich with detail and manoeuvre, with rock ‘n’ roll

business, musical chairs and stratospheric fame as David orchestrates his

(solo?) voyage across the bubbling sea toward his destiny as minor British

royalty uprooted to the West Coast.

Hence the title and subtitle of this

book, with so much meaning interred in those two words “sail away.” If I have

to spell it out once more: it’s about David leaving Britain, Brits and

Britishness for American shores, in turn transforming the band and brand into

an American monster, despite the United Nations of players represented in his

chimera-like and complex fiefdoms.

In any event, this was very much a

fulfilling detective job. Not so much for a huge divulging of the facts, which the

interested digger could ascertain for him or herself, but rather the organizing

of those facts and wafting from the tea leaves, much about human nature.

Essentially, however, the

fun of all this for me was the fact that I’ve grown up a variously frustrated,

non-plussed, hugely rewarded and connected-to-the-band Whitesnake fan. Said

lifelong abutment to the group and its catalogue begins with the

purchase as a new release of the Canuck [Canadian slang for Canada] version of the

first “album,”

Snakebite

, with the angry metalhead in me only liking it

mildly for the sips of angry metal on it.

Trouble

:

same deal. Looked great, loved that regal band shot on the back, but a little too

jazzy and bluesy for a teenager waiting for the NWOBHM to happen.

Lovehunter

?

Well, my exquisite blue pen rendering of that album cover on my social studies

notebook was the talk of the class! The gal looked sexier and the

snake, even more heavy metal, more martial and scowling.

Ready An’ Willing

...

began my education within, and appreciation for, how the blues can be added

ever so subtly to hard rock (Okay, not the first time... Zep, ZZ, Foghat,

Aerosmith), but an evolution in my thinking, let’s say, helped by David on a

mission.

Rock ‘n’ roll forward, and I was caught

up – just like everybody else – in celebrating Whitesnake 2.0, the

version successful in my part of the world due to

Slide It In

and

Whitesnake

(the latter featuring that sledge of all snow tractors, “Still Of The Night.”)

And there you had it, all of a sudden it’s a life of rock fandom, with this

band as a significant part of the soundtrack.

Later, I got into the business of

interviewing the heroes of my hobby, and that’s when I got to talk to splendid

Dave – who immediately puts everybody he converses with at their ease – along

with the aforementioned others. The magic and pixie dust of Whitesnake was over

after

Slip Of The Tongue

, but still, there were solo albums, such as

Coverdale

Page

; the live circuit and attendant live albums; then (to date,) two thick

and ferocious recent studio albums, which... well, it’s a long debate and I don’t

want to get into it here, but both

Good To Be Bad

and

Forevermore

fall into that category of debate revolving around “best albums of one’s

catalogue if you wipe the dates off the back and shuffle.”

Seriously, there are about ten of these

“heritage acts” who have blessed us with these very cogent modern-day records

when no one cares and no one is listening and the ship has sailed a long time

ago. Whitesnake is certainly one of those ten, thanks in large part to Doug

Aldrich, who helped Ronnie James Dio make his best late period album as well.

But alas, as you will read, moving ahead

through this celebration of the Whitesnake universe, this book will not be fighting

that battle at length. There is simply not enough word count assigned to the

project to do so. Looking at it another way, there was exactly enough word

count to do justice to the labyrinthine story of the classic years, namely up

to

Slip Of The Tongue

, that record’s spent aftermath, and the

death of hair metal. This is the story with the highest stakes with respect to the

business of the band, the most intense dramatic struggle, the

hue and cry of motivation and manipulation, and so this forms the

meat of the book. To be sure, the completist in me can’t resist presenting the

facts of the post-1980s period of drift, but, alas, that telling is perfunctory

and fleeting, as you will see, relegated to the “epilogue” ghetto.

And there you go. My mission here is to

put Whitesnake into the rock history books, in detail, and I guess until

someone does something more (including a book directly from David one day, one

hopes), it’s mission accomplished, to a great extent. In any event, I hope you

gain a new appreciation for the band, dislodged some of these records from your

shelves and rocked the blues one more time. At this end, man, I certainly got

to listen to a ton of great music once again, which had, for a spell, just

joined the thousands of other LPs and CDs lining the ol’ mancave office.

Until next time (er, that Gillan book,

wot?!), Saints & Sinners all, here’s trouble, Come An’ Get It.

Martin

Popoff

Early Years – “The

Unrighteous Bro

the

rs”

Pimply, pudgy, bespectacled, not much of

a dresser (despite his job selling pants – that’s trousers to you Brits) and

still weeks away from his 22nd birthday... this is the legend of a

less-than-unassuming David Coverdale on the verge of crashing his way into the

ranks of rock titans Deep Purple.

It’s the summer of 1973, and Purple is on

the ropes, in serious danger of disintegration. In a direct confrontation with

chaos, the responsibility to lead the band forward falls upon a nobody from the

North, notwithstanding the menacing presence of the Man In Black himself –

Ritchie Blackmore – checking passports at every border post looking for proof

of blues authenticity.

To be sure, our present tale is

Whitesnake, but would Whitesnake have been given half as much truck had

Coverdale not pushed forward with his folly already a

bonafide

rock star?

I think not. In that light, some scene-setting becomes necessary.

David Coverdale, (born 22 September 1951

in Saltburn-by-the-Sea (pop. 10,000), in the county of Redcar & Cleveland,

England) had been little more than a pub singer before answering a

Melody

Maker

ad seeking aspirers to the throne vacated by top rock yowler Ian

Gillan. And pub is the operative word here — Dave had been known to lift a few

bevvies around Redcar. In fact, his parents, of Irish heritage, had owned a pub

(mum has also been described as a school dinner lady and dad, a steelworker),

making the habit of quaffing a foaming brew an easy one to acquire. As well, Coverdale

has asserted that he’d been singing in North Yorkshire “working men’s clubs”

since the age of 11, having cut his teeth singing Tommy Steele medleys at home

from the age of 5.

“The main thing about the

working class is the determination to get the fuck out,” David told the

NME

. “My mother and father gave me full support within the

background of the Satanic mills. Nobody could put on any airs or graces — it

was two up and two down and an outside toilet. But I didn’t drown myself out. A

lot of people are satisfied to sit and watch the new James Bond film. Hollywood

has got a lot to answer for as well. Most of the people who make money spend the

rest of their lives trying to hold onto it and don’t enjoy it.”

“I discovered that I could express myself

much more with serious immediacy by singing,” mused David back in 1988,

speaking with

Rock Beat

, contrasting his chosen profession versus the

visual arts. “Rather than people looking at a painting and saying, ‘It’s nice,

what are you trying to say?’ I could express myself very simply and quickly and

people knew what I was talking about. I like that. I can’t remember this, but

my mother assures me that I could sing the entire Top Ten in those days.”

Coverdale’s first real band, Vintage 67, opened

for business in 1966. David had been bitten by the music bug, most viciously by

the Kinks, but also from the Pretty Things and the Yardbirds, though hardest by

Hendrix. Then came Denver Mule (‘67/’68) and The Skyliners (‘68/’69), followed

by The Government (‘69/’70), who had actually supported Purple back in August 1969

at a gig in Sheffield. It is said that Jon Lord took David’s phone number down

in case the then new boy Ian Gillan didn’t pan out as vocalist. All the

while, Dave was gathering a wage at the Purple Loon boutique and making his way

through arts courses in teaching and graphic design in darkest Middlesbrough,

where he first made the acquaintance of future Whitesnake mate Micky Moody.

Coverdale told

Circus

that he’d packed in college because, “I found I

could use my body and voice for self-expression, to communicate with people

right on the spot, even with a silly song.”

Back on the music track, leading up to

his ascendance through Purple, David was crooning for the likes of Harvest

(which got as far as Denmark), River’s Intention and finally The Fabulosa Brothers.

At one point, he had been offered the chance to sing with respected progsters

The Alan Bown (A.K.A. The Alan Bown Set and Alan Bown). “A friend of mine who

knew them told me they were interested in me and wanted to know if I’d sign up.

I thought he was kidding and jokingly told him, ‘Fuck off.’ Unfortunately he

took me literally.” Robert Palmer, Mel Collins and Jess Roden all passed

through the ranks of Mr. Bown’s esteemed band, so you can see why Coverdale

felt he had made a bit of a

faux pas

.

Lesson learnt! After having sent in a

cassette and subsequently put through the Purple paces in August of 1973, to

everyone’s surprise, Coverdale landed this slightly bigger gig. More surprisingly,

David had to be persuaded to apply for it by a buddy, and what his audition

tape contained was a drunken rendition of Harry Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talking,”

about which Jon Lord said David barely followed the tune.

“Purple’s office asked me to send a

photograph of myself which I thought was a bit daft,” recalled David, speaking about

his hiring to

Music Express

in 1977: “I wondered why they

would judge a person’s talent by his looks. The photo I sent down I had to

borrow from my mother. It was one of me in my Boy Scouts uniform.

“Then they asked for a tape of my voice

and the only tape I had was one of me singing at a party when I was drunk. I

thought I’d had it, but I was invited down to London for an audition and I got the

gig. I guess what attracted them was the tone of my voice rather

than what I was singing. I was just a local yokel, you know, local boy makes

good and all that stuff. I’d never even been in a recording studio before we

went in and cut

Burn

. Now I’m a local hero in Saltburn. They gave me the

keys to the town; they also asked me for £25,000 to restore an old bridge but I

had to turn them down.”

David muses: “I remember being so keen. Remember,

Burn

was the first record I ever made. I knew Deep Purple was big in

England, but I had no idea of the global aspect of it, so it was mind-blowing

when I got that job. And the band was very supportive and still, to this day, I

applaud their courage in taking a risk. No question, I was completely unknown.

Obviously they thought I had something, God bless them.

“But the circumstance is, what a brave

thing to do for a band of that size. But Ritchie and I did most of the

writing on there. In those days, they split everything five ways which was their

agreement, which Ritchie changed after

Burn

. There’s a certain laziness.

If you don’t have to work you don’t contribute as much, and there

was evidence of that. So he changed that dynamic on

Stormbringer

and

Purple weren’t very happy about that at all; the old guard. But anyway, what

Ritchie said went. I wrote at least six versions of the song ‘Burn,’ I was so

fucking keen.”

One of those sets was a blues thing David

had called “The Road,” but, amusingly, he figured he’d better keep Ritchie

happy, so he came up with the “sci-fi poem” that proved to be the

keeper. The blues would have to wait.

Critical to the hue and dimension of

David’s hiring would be the recent arrival into the Purple ranks of a bass

player who also sang quite well, thank you very much; a gent by the

name of Glenn Hughes. Coverdale recalls: “One of the ridiculous things was that

Glenn was such a talented singer, but Ritchie wasn’t such a big fan of Glenn’s

voice. He liked my voice. He said, “You have a great man’s voice,” which was a

pretty nice compliment. And he didn’t exactly get the same vibe from Glenn.

There is no question that Glenn is extraordinary. Technically he can sing me

into the ground, but I can connect deeper emotionally.

“But what happened is that prior to me

getting the job, he really felt that he was going to be the lead singer and

bass player and that really is not what Ritchie was after. So once they

got the ‘man’s voice’ in... And Glenn and I have talked about this; it was

ridiculous that I would sing a line, he would sing a line, I would sing a line,

he would sing a line, I would sing a chorus, he would sing a chorus. It was

just all over the place. One of the perfect examples was the song ‘You Fool No

One,’ where we sing it together, or ‘You Keep On Moving,’ and then

we’ll each take a break on something else, you know, another sequence of the

song. But for anybody wanting to get their hooks into a song, to have this

confusion of different voices coming in left right and center is more a

distraction than a hook.”

Having two purposeful singers in the

band wasn’t an insurmountable problem, but it was a challenge and a

contributing factor to the eventual happenstance that is Whitesnake. But for

now, it was a beautiful thing watching the creative tension between David and

Glenn, not to mention between David and Glenn versus the trunk of the

band, namely Ian Paice, Jon Lord and Ritchie Blackmore.

And there were no confidence issues with

Coverdale, notes Hughes. “No, David never really suffered from that. David,

when he first came into the band, he was a little green, but he developed. We

saw, right in front of us, him developing his own style back then.

Which took him to Whitesnake. I mean, he became pretty strong, at the

end of the

Burn

tour and into

Stormbringer

. We weren’t the

new boys anymore. He’s a strong character.”

Hughes believes that: “There were no

struggles with David in terms of getting him to lose some weight, pop in some

contact lenses... Well, I think he wanted that for himself. I mean, David, from

the get-go, was very professional. Obviously he hadn’t worked in this genre

before, ever. So you just need the blueprint of how to do it. I’d been on the

road for three or four years with Trapeze, and David and I had been, and were, the

very best of friends.

“You know, people ask me were there

problems and this and that? I think if you interviewed David he would say there’s

never really been any problems with him and me. My singing didn’t deter him

from his goal, and his singing didn’t deter me from mine. We were a great team.

We were the greatest vocal duo in rock. And I think we still are, when you look

back, the only two singers that were really dominant in that role.”

“When they asked me to join, I said no,”

recalls Hughes. “I did not want to be just a bass player. I just wanted to be the

singing bass player from Trapeze, where my heritage was started. And that’s

what I am today. I’m the singing bass player/lead singer. But I did think that the Coverdale/Hughes connection, with me being the secondary singer, if you will... I’ve never

had a problem in that role, because I always think I’m going to be a student of

the voice until the day I die. I think that anybody who thinks that they

are the finished article is bullshitting. So I think what Coverdale and Hughes

had to offer has never been reproduced by anybody.”

Coverdale can thank Blackmore for his big

break, says Hughes. “Yeah, first of all, he wanted Gillan out, and Gillan left.

Definitely he wanted out. Because Gillan was crazy back then; I think he just

wanted to be away from the business. And Roger Glover was let go in order for

me to come in. Bruce Payne [Purple’s manager] wasn’t involved in that. Ritchie

did everything. Ritchie ran that thing with an iron-clad fist.”

Were the guys worried or, at least,

hesitant about David’s abilities? “There was no problem with his voice, but he

was very green in the fact that he had never done any arena shows. He had never

been on a stage bigger than a club stage. I think the first gig we did with

David was maybe in Denmark: 10,000 people. So he jumped in with both feet.

David Coverdale is a charismatic guy, even before he was famous. He was perfect

for the role.”