Salem Witch Judge (30 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

Mexico struck him as a likely locale. Some years later, after hearing Increase Mather refer in a sermon to the bright morning star as “a sign in the heaven,” Samuel was amazed to observe a comet pass over his house. It was “a large cometical blaze, something fine and dim, pointing from the westward, a little below Orion,” the dominant constellation in New England’s night sky. Samuel used a ship’s globe to

show a sea captain, Timothy Clark, how the comet’s trajectory pointed to Mexico. “I have long prayed for Mexico,” he said, “that God would open the Mexican fountain.” Mexico City was far more populous than any other town in North America. In 1700 Mexico City had more than 100,000 residents, roughly the number of people in all of New England.

There were practical reasons to make America the New Jerusalem, Samuel observed. From the perspective of someone in England, “the situation of Jerusalem [in the Middle East] is not so central…. A voyage may be made from London to Mexico in as little time as from London to Jerusalem. In that respect, if the New World should be made the seat of the New Jerusalem, if the city of the Great King should be set on the Northern side of it, Englishmen would meet with no inconvenience thereby, and they would find this convenience, that they might visit the citizens of New Jerusalem and their countrymen all under one.”

As he was trained at Harvard, he took the opposite view from the one he wished to propound. “What concernment hath America in these things?” he asked rhetorically. “America is not any part of the Apocalyptical stage. The promise of preaching the Gospel to the whole world is to be understood of the Roman Empire only,” which “contained about a third part of the old World, and this triental [third] only was to be concerned with the Apocalypse.” The standard view was, “The prophesies of the Revelation extend…not to the West Indians, not Tartarians, nor Chinese, nor East Indians.”

He turned a corner with a biblical metaphor: “But what shall we say if the stone which these builders have refused should be made the head of the corner?” The Acts of the Apostles 4:11 describes Jesus Christ as “the stone which was set at nought of you builders, which is become the head of the corner.” In other words, America, which like Jesus Christ was at first rejected, might become the cornerstone of the new kingdom of God on earth. Samuel justified his foray by saying, “The word of God is not bound.”

By the end of that summer following his public confession, Sewall sensed that his pastor no longer ostracized him. Relieved, he invited Willard’s family to attend a picnic he hosted on Hog Island on October 1. He arranged for boats to transport his own five children, who now

ranged in age from nineteen to six, and his twenty-three-year-old niece, Jane Tappan, Jeremy Belcher’s three sons, who were ages eighteen to twenty-eight, and four children and one nephew (eleven-year-old Edward Tyng) of the Willards. Hannah Sewall stayed home “through indisposition,” but Samuel “prevailed with Mr. Willard to go” too.

The party had “a very comfortable passage thither.” On the island they snacked on “butter, honey, curds,” and cream. Their dinner consisted of “very good roast lamb, turkey, fowls, [and] apple pie.” Hannah had sent bottles of “spirits” to drink. Carelessly, someone left a glass of spirits on a joint-stool. Simon Willard, who was twenty-one, inadvertently knocked the glass to the ground, breaking it “all to shivers.”

“’Tis a lively emblem of our fragility and mortality,” Samuel remarked to his pastor. Willard understood exactly. For these Puritans, the historian David Hall noted, “the unexpected crash of a glass to the floor was like the crash of God’s anger breaking in upon the flow of time.” Time was not regular for them because time belonged to God. “Though prophecy unfolded, though the clock ticked away the hours by an unvarying beat, though the seven days of Genesis were stamped immutably upon the calendar, the will of God stood over and above any structures…. All existence was contingent, all forms of time suspended, on his will.” As Samuel himself would say two years later, when a downpour of rain destroyed orchards and cedars throughout his neighborhood, “How suddenly and with surprise can God destroy!”

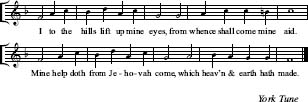

Before departing Hog Island Samuel led the group in singing Psalm 121, which he considered appropriate to the setting.

I to the hills lift up mine eyes,

from whence shall come mine aid.

2 Mine help doth from Jehovah come,

which heav’n & earth hath made.

3 Hee will not let thy foot be mov’d,

nor slumber: that thee keeps.

4 Loe hee that keepeth Israell,

hee slumbreth not, nor sleeps.

5 The Lord thy keeper is,

the Lord on thy right hand the shade.

6 The Sun by day, nor Moone by night,

shall thee by stroke invade.

7 The Lord will keep thee from all ill:

thy soule hee keeps alway,

8 Thy going out, & thy income,

The Lord keeps now & aye.

That autumn Samuel continued to work on his prose poem. Again and again he returned to the same questions: What place will Jesus Christ choose for his New Heaven? Will the inhabitants be Protestant or Catholic? Where on earth will the apocalypse begin?

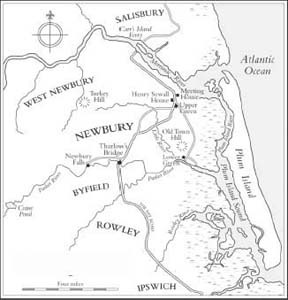

A salt marsh alongside the mouth of the Merrimac River in northeastern Massachusetts overlooks the landscape of Samuel’s musings on the book of Revelation, as outlined in his 1697 essay, Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica ad Aspectum Novi Orbis Configurata, or, as he translated his own Latin, “Some few lines towards a description of the New Heaven, as it makes to those who stand upon the New Earth.” In this coastal region to which he had arrived as a boy of nine, the repentant judge envisioned the future Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

How many times had Samuel set out from here by boat? He could no longer say. This was the usual point of departure to Plum Island, a slender barrier island dotted with scrub pines and junipers running parallel to the coast for nearly nine miles. He knew Plum Island almost as well as Newbury. A few people inhabited it, countless cattle grazed there, and farmers stacked salt-marsh hay on the island. Plum Island offered protection to Newbury by keeping the rough, cold Atlantic Ocean at bay, literally, and making the inland waters warm, shallow, and calm.

As a boy Samuel often rowed his dory south from here along Plum Island River, the narrow estuary between Newbury and Plum Island. Looking all around he could see only water, sky, and lime green marsh

grass. Now and then a snowy egret dug for food in the mud. Hardly two miles to the south, near the mouth of the Parker River, Plum Island Sound opened up and spread out. The sound, an oval body of water between Plum Island and the mainland with a depth of only six to eight feet, teemed with striped bass, cod, haddock, herring, flounder, mackerel, and sturgeon. Plum Island Sound was roughly the center of the Great Marsh, a vast wetland area extending about seventeen miles along the northern Massachusetts coast from the towns of Salisbury to Gloucester. It was here, Samuel prophesied, that Christ would return to earth.

“As long as Plum Island shall faithfully keep the commanded post,” he wrote in the magnificent part of Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica

that is often excerpted in collections of colonial American literature and that foreshadows much later pastoral odes such as “To Autumn,” by John Keats.

As long as Plum Island shall faithfully keep the commanded post; Notwithstanding all the hectoring words, and hard blows of the proud and boisterous ocean; as long as any salmon, or sturgeon shall swim in the streams of Merrimac, or any perch, or pickerel, in Crane Pond; as long as the sea-fowl shall know the time of their coming, and not neglect seasonably to visit the places of their acquaintance; as long as any cattle shall be fed with the grass growing in the meadows, which do humbly bow themselves down before Turkey Hill; as long as any sheep shall walk upon Old Town Hill, and shall from thence pleasantly look down upon the River Parker, and the fruitful marshes lying beneath; as long as any free and harmless doves shall find a white oak, or other tree within the township, to perch, or feed, or build a careless nest upon, and shall voluntarily present themselves to perform the office of gleaners after barley harvest; as long as nature shall not grow old and dote, but shall constantly remember to give the rows of Indian corn their education, by pairs: So long shall Christians be born there; and being first made meet [fitting], shall from thence be translated, to be made partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light.

Samuel perceived the beauty of this landscape as evidence of its spiritual truth. In his view God granted this gorgeous New Israel to his people, the “saints in light,” so they might worship him. “Now,” he went on, “seeing the inhabitants of Newbury, and of New England, upon the due observance of their tenure, may expect that their rich and gracious Lord will continue and confirm them in the possession of these invaluable privileges: Let us have grace, whereby we may serve God acceptably with reverence and godly fear, for our God is a consuming fire. Heb. 12:28–29.” After much consideration, Samuel now believed that Christ would choose America, and more specifically Plum Island on Boston’s North Shore, as the location of his kingdom of God on earth.

Literary scholars point to the Plum Island passage, as it is known, in Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica as the beginning of American literature as such—conscious of itself as American rather than European and with a positive stance toward the land. (The text of Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica begins on page 289.) Prior to Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica, the historian Perry Miller wrote, English-American writers portrayed America as a frightening, obscure, threatening “wilderness” full of beasts and French and Indian terrorists. In Samuel’s new vision the wilderness is beautiful and godly, a place where Jesus Christ might and would reside.

“It is not too much to say that this cry of the heart signalizes a point at which the English Puritan had, hardly with conscious knowledge, become an American, rooted in the American soil,” Miller added. “Suddenly reminded of Plum Island,…where he himself had played as a boy,” Sewall was “carried away into this prose poem on the earthly, the sensuous, delicacies of the land [that] he, good Puritan as he resolutely was, had learned to love with a fervor as passionate as that which he held in reserve for the heavenly kingdom.” In this essay Sewall “yielded—as no Puritan could have contrived to do without subsuming his love under a millennial destination—to that delight in the American prospect which for over half a century had been perversely nourished under the canopy of his jeremiads.”

Sewall’s newfound feeling—of love for the land itself—reappears throughout American literature. “The land was ours before we were the land’s,” the poet Robert Frost wrote in “The Gift Outright.” Frost’s poem was itself an echo of the Reverend John Cotton’s 1630 argument that “the land belonged to them [English Puritans] before they belonged to the land,” according to the scholar Sacvan Bercovitch. Claiming the land by charter or deed did not make it thereby one’s true home. Bercovitch observed that Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica puts Sewall in a select group of New England writers who “successfully pierced natural images to reveal supernatural truths,” a group that includes Jonathan Edwards, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau. David Lovejoy, another scholar, said Sewall’s essay marked the moment when English settlers “took [America] into themselves.” This distinguishes Sewall from the early New England poet Anne Bradstreet, who, according to Perry Miller, “wrote only of English streams

and English birds.” With Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica, Miller added, “Sewall seems to have put his spiritual crisis behind him, for he ‘found salvation in surrender’ to the land and its people.”

Sewall’s concept of America was new in another way. Rather than linking the land’s spiritual significance to the arrival of Christian Europeans, he considered America’s divinity inborn, thus present before those settlers arrived. For Sewall, America’s people included not only Puritans and other new arrivals but also its native tribes. Indians became central to his argument about America’s role in the apocalypse. Decades before, the Reverend John Eliot had conjectured that American Indians were not savages, as so many English thought, but a holy people—members of one of the ten lost tribes of Israel. Many Indians are “true believers,” Sewall added in his essay on Revelation. “Mr. Eliot was wont to say the New English churches are a preface to the New Heavens…. If Mr. Eliot’s opinion prove true—that the aboriginal natives of America are of Jacob’s posterity, part of the long since captivated ten tribes, and that their brethren the Jews shall come unto them—the dispute will quickly be at an end.”