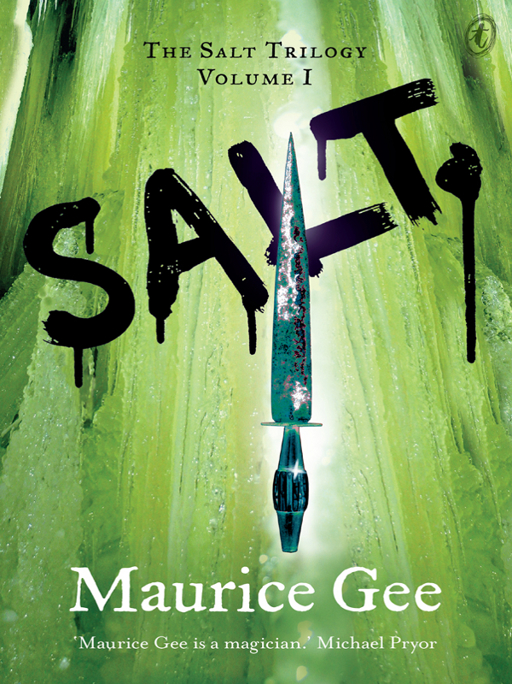

Salt

Praise for Maurice Gee and

Salt

W

INNER

, N

EW

Z

EALAND

P

OST

B

OOK

A

WARDS

Y

OUNG

A

DULT

F

ICTION

S

ECTION

2008.

S

HORTLISTED

, E

STHER

G

LEN

A

WARD

2008.

‘From a storyteller who makes the craft look effortless…

Salt

is

brutal and uplifting in equal measure.’

Bernard Beckett

‘Deft, subtle, artful, Maurice Gee is a magician. He has created

another world and he takes us there without showiness or effort.’

Michael Pryor

‘I picked up

Salt,

Maurice Gee’s new young adult fantasy, one

evening...and I didn’t put it down again…The strength and

clarity of the prose, the simple, compelling story woven through

with ideas of fundamental importance…this is in my view the

best children’s book of his long career.’

Listener

‘Spare, disturbing but ultimately optimistic—the magic of

Salt

is all in the writing…gritty understated clarity and sharp

imagery…an utterly compelling read.’

NZ Post Book Awards Judges’ Report

‘A skilfully told story, taut and fast-moving, but with a rich

texture of dark reality to it.’

Magpies Australia

‘It is a marvellous moment when you read the first page

of a new book and realise you are holding a classic of the future.

Salt

is a stunning mix of action and ideas…

a master storyteller at his peak.’

Weekend Press

Maurice Gee is one of New Zealand’s finest writers. Born in 1931, he has written more than forty books for adults and young adults. Gee has won several literary awards, including the Wattie Award, the Montana Deutz Medal for Fiction, the New Zealand Fiction Award and the New Zealand Children’s Book of the Year Award.

Gee’s young adult novels include

The Fat Man

,

Orchard Street, Hostel Girl, Under the Mountain, The O Trilogy

and

Salt

and

Gool

, the first two books of

The Salt Trilogy

. Maurice Gee lives in Nelson, in New Zealand’s South Island.

THE SALT TRILOGY

VOLUME I

Maurice Gee

The paper in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Maurice Gee 2007

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in Puffin Books by Penguin Books (NZ), 2007

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2009

Design by Mary Egan

Typeset by Egan Reid Ltd

Map by Nick Keenleyside

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Gee, Maurice, 1931-

Salt / Maurice Gee.

ISBN: 9781921520082 (pbk.)

NZ823.2

Ebook ISBN: 9781921834486

The Whips, as silent as hunting cats, surrounded Blood Burrow in the hour before sun-up and began their sweep as the morning dogs began to howl. Rain fell heavily that day, washing the streets and overflowing the gutters. The grey tunics of the Whips turned black in the downpour, their helmets shone like beetle wings, and the sparks that jumped from their fingers as they herded their recruits fizzed and spat like sewer gas.

They took ninety men, some from their hovels, some from the ruins, and prodded them, howling, to the raised southern edge of People’s Square, where the paving stones had not yet slipped into the bog. Brown water lapped the buildings on the northern side. Cowl the Liberator, crying Liberty or Death, raised his marble head above the rushes. Mosquitoes bred underneath his tongue. The Whips, as custom required, paused in their herding and mouthed ‘Cowl the Murderer’ before going on.

A cart with a covered platform and canvas aprons at the sides and back waited on the stones. A clerk sat at a desk under the awning, with a sheaf of forms under his palm and a quill pen, curved like a blade, in his other hand. His uniform was paler than the Whips’ (and dry) and had the Company symbol, an open hand, blazoned on the tunic. He frowned at the rabble herded in front of him, and drew his head back in a vain attempt to avoid the stench of rotting shirts and festering bodies.

‘Sergeant.’

‘Sir?’

‘Is this your best effort? My orders are two hundred fit for work.’

The Whip sergeant swallowed and seemed to shrink, knowing he and his men would earn no bonus, even though they had chased hard, sparing none. ‘They fled like rats. They have holes and runways everywhere.’

‘And your job is to know them and bring me no starvelings, no half-dead.’

‘They pretend, sir. This one –’ he prodded a near-naked man, making him whimper – ‘he ran like a marsh deer. Now he stoops. And this – he has swallowed dirt. It makes him vomit.’

‘Enough. I know their tricks. Count.’

‘Ninety, sir.’

‘Silence them. And the women too.’

The Whips raised their electric hands and shot fizzing bolts into the air and the howling stopped. Outside the ring of guards, the wives and children of the ninety fell silent. Some kept their mouths wide in cries they dared not utter, while others wept soundlessly, their tears mingling with the rain, which fell more heavily, making puddles round their unclad feet.

The clerk stood up under the awning. ‘Men,’ he cried, widening his mouth in a smile, ‘this is your great day. You are chosen to serve Company in its glorious enterprise. Daily we grow in comfort and prosperity. In this you share. Who serves Company serves mankind. Raise your voices now and give thanks.’

The men closest to the Whips made a few ragged shouts, ‘Long live Company. Praise to Company,’ but somewhere a woman shrieked, ‘Murderers!’ And from the ruined buildings round the square cries like echoes came from doorways and windows: ‘Murderers, thieves!’

The clerk was untroubled. His speech was part of procedure, and the shouts and cries, and the howling and tears, were something he expected on recruiting days. He sat down and yawned behind his hand.

‘Examination,’ he said.

A Whip prodded a man into the space before the cart, then, with his gloves turned off, stripped off his clothing with raking sweeps of his iron hands. The man, young but stooped and thin, stood shivering in the rain.

‘No need for the hose today,’ said the clerk, but he yawned again while his underlings sprayed the man’s body with disinfected water from a tank behind his wagon.

‘Name?’

‘Heck,’ the man whispered.

The clerk took his quill and wrote on a form.

‘Deformities?’ he said to a third underling who had stepped down from the cart.

‘None.’

‘Sores?’

‘Multiple. Feet and legs.’

‘Condition?’

‘E.’

The clerk ran his eyes over the man’s body. ‘You bring me trash,’ he said to the sergeant.

‘Sir, he is fast. He goes like a mud-crab. He will fit in narrow places.’

‘Perhaps.’ The clerk frowned at Heck. ‘Saltworker,’ he said.

‘No,’ cried the man, falling to his knees. ‘Not salt. I’ll go to the farms. I’ll go on the ships. In the name of Company, I pray you, not salt.’

‘Brand him,’ said the clerk, tossing a marker to the underling.

The man beckoned his helpers for the acid bucket and the brush. He fitted the metal marker on Heck’s forehead while a Whip held him still, and swiped the brush across the stencil. ‘Who joins Company joins history. Your time begins,’ he intoned, ignoring Heck’s screaming as the acid burned.

‘Name him,’ said the clerk.

The underling read from the marker: ‘S97406E.’

The clerk wrote.

‘Is there a woman? Quickly. Come.’

A woman doubled up with age scuttled through the ring of Whips and stood in front of the cart.

‘You are his?’ said the clerk.

‘His mother, sir. He has no wife. He could not keep a woman.’

The clerk shrugged. ‘Give it to her.’

The underling handed an iron token to the crone, who seized it and hugged it to her breast.

‘Show this at the Ottmar gate on the morning of the last day of each month. Company will pay you one groat. Nothing if it is lost. Do you understand?’

‘Long life to Company. Company cares,’ said the woman. She scuttled back through the Whips, with the marker hidden in her rags.

‘Company cares,’ the clerk replied, speaking by rote. ‘Next.’

The rain continued to fall. The numbering and branding went on until mid-morning. Under the cart, Hari knelt on the stones, shifting only to ease his legs and holding his knife ready to stab. The horses knew he was there but he had made a bond with them as he found his hiding place. Now and then he slipped his hand under the canvas apron and touched each one on the fetlock, as light as a fly, renewing that bond. He had cut a flap like an eyelid in the side-canvas, and he watched as each recruit was held and branded and each wife or daughter given a token, and he was filled with hatred and rage, which he had to hold down, and aim away at the Whips and the clerk, so it would not alarm the horses. He must keep them calm, and use them when the time was right. He watched his father, who had two names, Tarl and Knife.

He had thought they would never take his father, and Tarl himself had made a vow that he would die before letting Company enslave him. Yet here he was, held within the ring, burned on his chest and arms by electric fingers, and waiting his turn for the brand.

The early howling of the dogs had woken them that morning, in their corner of the ruined hall known as Dorm, and Hari had read the message in their howls, and run among the sleeping tribe, waking them with kicks and cries: ‘The Whips are coming.’

‘Wake the burrow, I’ll do the streets,’ his father had shouted, so Hari plunged through stairwells and runways and pits, on sloping beams, on slides of rubble, shouting his warning: ‘The Whips, the Whips!’ Men scurried into the dark, deeper into holes inside Blood Burrow. A hundred or more made their escape.

Tarl had chosen the more dangerous way, warning men in the shelters opening off the streets – and somehow the Whips had cornered him and locked him in their fizzing ring. Hari, at the end of his run, watching from a crevice in the base of a shattered wall by People’s Square, had seen the ninety herded round the edge of the swamp, and seen with disbelief his father among them. The clerk’s cart had rumbled by, a body length from his nose, heading for its place by the south wall. Hari had not thought; he had acted, the way the feral dogs, the way the deep-crawling, invisible rats had taught him. He darted across the stones, slid under the canvas apron, rolled between the iron-clad wheels and fastened himself like a cockroach to the underside of the cart. He felt the horses sense him and replied in a silent whisper: Brother horse, sister horse, I am here, I am you.

Eighty-nine men were stripped and branded and named and stood shivering in the bitter rain, each with his hands tied at his back and a rope halter fastening him to the man in front. His father was the last, and Hari, watching through his eyehole in the canvas, saw why he had worked himself into that position. Inside Tarl’s ragged shirt, in its ratskin sheath, his knife was hidden. He had won space for his throwing arm. The clerk would die. Hari heard his father’s intention like a whisper.

No, he tried to whisper back, I have a better way. He was too late.

Tarl writhed and cowered, with his limbs locked in crooked shapes as though by disease. The Whip stepped close, turning off his gloves. He raised his iron fingers to strip Tarl’s clothes, and in that moment Tarl became himself – stepped in and out, with his black-bladed knife in his hand, and slashed like the blow of a fangcat. The Whip fell back, shrieking, as his cheek between his helmet’s eye- and jaw-piece opened up.

A single leap sideways gave Tarl room. He turned in the air and landed facing the clerk. The knife spun in his hand as he reversed it. But even as it sped away with a whipping sound Hari saw his father’s error. The blade was slippery with blood, and Tarl’s fingers had slid at the last moment, lowering the trajectory. The knife struck the edge of the desk. It bounded back and fell on the stones. And already Whips, with gloves sparking at lethal power, surrounded his father and moved in.

‘Hold him. Don’t kill him,’ cried the clerk.

They paused an arm’s length away and held Tarl immobile in their hissing ring. His clothes began to steam and smoulder, and the clerk cried, ‘Back. Further back. I want to see him.’

The Whips retreated a single step.

‘Strip him,’ said the clerk.

The Whip sergeant raked Tarl’s body, making him scream. Tarl stood naked in the rain.

‘Yes, I see. No crooked man after all. You will serve Company well. What a pity it is we cannot use your knife skills. I might have posted you to Company Guard. But after attacking a Whip and trying to assassinate me, you have lost your chance.’

‘I will join no Company. I belong to myself. I’m a free man,’ Tarl cried.

The clerk gave a smile and said patiently, ‘Yes, that is true. Everyone is free. But freedom means serving Company. Is that not understood in the burrows?’

‘You use us to enrich yourselves. You starve us and turn us into slaves.’

‘There is a time of hardship,’ said the clerk. ‘For everyone. But Company works for all and the benefit will reach here soon. It comes down like the soft rain, even into Blood Burrow, you will see. Perhaps it is time we sent educators here. But enough talk. What is your name?’

‘I have none for Company. It is mine,’ said Tarl.

‘Then keep it,’ said the clerk. ‘I’ll make you a new one.’ He spoke to his assistant, who punched out a stencil. The clerk threw it down to the underling.

‘Brand him,’ he said.

Two Whips with gloves at quarter power forced Tarl to his knees. Even so, his limbs jerked with pain. The underlings, one with the stencil, one with the acid, branded him. Tarl cried out, but not with the burning. ‘I do not accept this. I am Tarl.’

The clerk picked up his quill. ‘Not any more, I’m afraid. Yes, man, read it.’

The underling obeyed, and a moan of fear went up from the haltered prisoners and the women gathered by the swamp.

‘DS936A,’ the man read.

Under the cart Hari closed his eyes in terror. DS was Deep Salt, the furthest reaches of the deepest tunnels of the mine. Men sent there never returned to the surface. What they dug for nobody knew, and after a time, one by one, they vanished. No bodies, no traces of a body, were ever found. It was said the salt worms took them, or salt tigers, or salt rats, but these were make-believe creatures no one had seen. It was said their souls were sucked down into the dark lake at the centre of the world and locked in cages forever. Hari believed it. He knelt with his forehead on the stones, shaking with fear. The cart horses whinnied and rippled their hides as though stung by flies.

Outside, the Whips stepped back from Tarl, and after a moment he rose from his knees.

‘I am still, I am always, a free man,’ he said, but his voice was thin and afraid.

‘Who you are is DS936A,’ said the clerk. ‘And I offer my congratulations. It is the first time I have given an A. Your woman will get two groats instead of one. Where is she?’

‘I have no woman. And I will take nothing from Company.’

‘Then Company is spared the expense, which is to the good. Bind him, and make it tight.’

The Whips obeyed, while Hari, under the cart, raised himself from the stones and crept to his eyehole again. Stay, he commanded the horses, do not move. He saw how the Whips pulled his father’s halter tight and tied double knots to bind his hands. But Tarl had no man fastened behind him. A single knife-slash would cut him free.

‘Let no man think he can change his destiny, which is service to Company,’ said the clerk. ‘You will march now, ninety servants in the glorious enterprise, to the dispersal centre, where you will find clean tunics, each emblazoned with the open hand, and food, good food, enough to satisfy strong men like you. Company cares.’

‘Company cares,’ murmured several of the recruits, for ‘food’ and ‘enough’ were words seldom heard in the burrows.

The clerk smiled. ‘From there you will go to your new work – to Ships, to Coal, to Farm, to Factory, to Granary, to Salt –’ he smiled again – ‘and to Deep Salt. Each will serve out his time, and payment will be made to your women here at home. Company cares. And when you have made your contribution and wish to labour no more, you will retire to a Golden Village as honoured workers of Company, and your women will join you to live out your lives in quiet enjoyment. That is the happy future Company prescribes for you! Now march like men. March like servants in our enterprise.’

‘And march to your deaths,’ Tarl cried, ‘for there is no retirement. You will work until you die. That is the only use Company has for you.’

The Whip sergeant stepped at him with his hands raised, but the clerk cried, ‘Leave him. Let him rant. He goes to Deep Salt, and it is true, no man returns from there. But let me ask you, fellow –’ he squinted at Tarl’s forehead – ‘DS936A. Are there any more hidden in the burrows like you? Do you have followers, do you spread your poison among our happy citizens there? We must investigate. A brother perhaps? A son to follow in your ways?’