Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (15 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

BOOK: Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women

12.96Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

When the happy trio returned to England, the public waited with bated breath to see what happened next. Lady Nelson was sure her husband would see the error of his ways and get rid of his mistress but it was too late. As soon as Emma set foot on English soil it was clear that she had the upper hand. She was about to give Nelson the one thing that his wife couldn’t: a child, preferably a son. During her pregnancy, Emma started a fashion craze for high-waisted dresses, which was essentially a maternity dress. Lady Nelson was toast. Nelson insisted on a separation, making her a generous settlement.

In January 1801, she was granted her wish, when she gave birth to Nelson’s daughter, whom she named Horatia. After the birth, Nelson wrote, “I love, I never did love any one else. I never had a dear pledge of love til you gave me one, and you, thank my God, never gave one to anybody else.” Emma found them a country home just outside London for the three of them to live in, adding Horatia under the guise of an adopted child. Nelson bought it sight unseen and Emma decorated it like a mini Nelson museum filled with memorabilia. She entertained lavishly to promote Nelson’s career, inviting his nieces and nephew to give the whole thing an air of respectability, while Sir William fretted about the incessant partying and the bills. He tried desperately to get the government to pay him back for all the antiquities he’d lost in the flight from Naples and to secure a pension for his thirty years as ambassador there.

The idyll ended with Nelson’s death in 1805 at the battle of Trafalgar. Emma had already lost Sir William in 1803, but Nelson’s death sent her into despair. She collapsed, crying, “My head and heart are gone.” She was too ill to view the body while it lay in state at Greenwich Hospital, and she was pointedly excluded from his funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Emma had to queue up to see her lover like everyone else. He belonged to the nation, no longer just to her. She spent the day of the funeral in tears, surrounded by her mother and Nelson’s female relatives.

She was also deeply in debt. Emma had always lived beyond her means, and now with limited funds from Sir William’s estate,

8

she was hard-pressed. Despite Nelson’s dying wish that the nation should take care of his mistress, no money was ever forthcoming. For the next several years Emma tried to keep up appearances, giving lavish parties for her friends. She was also supporting several of Nelson’s relatives as well as her own poor relations. Three years after his death she owed thousands of pounds to a host of creditors. Worst of all, her mother died in 1810, leaving Emma without the one person she could truly rely on. Soon she was forced to sell Merton, the home she had shared with Nelson, and many other mementos of their life together, including his letters.

8

she was hard-pressed. Despite Nelson’s dying wish that the nation should take care of his mistress, no money was ever forthcoming. For the next several years Emma tried to keep up appearances, giving lavish parties for her friends. She was also supporting several of Nelson’s relatives as well as her own poor relations. Three years after his death she owed thousands of pounds to a host of creditors. Worst of all, her mother died in 1810, leaving Emma without the one person she could truly rely on. Soon she was forced to sell Merton, the home she had shared with Nelson, and many other mementos of their life together, including his letters.

A wiser woman would have quickly tried to find another husband or at least a protector. But when one has been the beloved of one of the greatest heroes England had ever known, how could any mortal man compete? Emma finally fled with Horatia to Calais in 1814 to escape her creditors. By now her health was ruined from too much rich wine and food. Taking to her bed, she was nursed by a distraught Horatia, who begged to know the truth about her parentage, but Emma refused. Although Horatia had been told that Nelson was her father, Emma never admitted that she was her natural mother. Racked with pain, Emma died on January 15, 1815. She was buried in Calais, far from her lover Nelson. Horatia was taken in by one of Nelson’s sisters. She later married a clergyman and had eight children. Like a true Victorian matron, Horatia was happy to claim the naval hero Lord Nelson as her father, but she refused to believe that the notorious Emma was her mother.

Emma’s story continues to fascinate because it is a story about ambition and heartbreak, love and pain. She rose from the depths of poverty to the heights of fame and fortune, only to end up back where she started. Her childhood had left her ambitious, and hungry for the limelight, but it was a hunger that could never be appeased. Emma always wanted more. Like Icarus in the Greek myth, perhaps she flew too high.

I have known all the world has to give—ALL!

—LOLA MONTEZ

Lola Montez was the International Bad Girl of the Victorian era, wrecking havoc on three continents. Victorians lived vicariously through stories of her adventurous life, whether they were true or not, the more outrageous the better—that she bathed in lavender, dried herself with rose petals, that a man once paid one thousand dollars for an evening’s performance. She was an actress, a writer, a lecturer, and the most famous Spanish dancer in the world who wasn’t actually Spanish. Even the minor incidents of her life could fill hundreds of romance novels.

Lola started life as the less exotically named Elizabeth Rosanna Gilbert in 1820, although some biographers claim that she was born earlier, in 1818, and Lola herself shaved years off her age. Her father was a soldier in the British army, and her mother was the fourteen-year-old illegitimate daughter of the High Sheriff of Cork and an Irish MP. The young family set off for Calcutta, where Eliza’s father died from cholera soon after they arrived.

Her mother soon remarried, to another career army officer. Only eighteen, she became caught up in the social life in Calcutta and had little inclination for motherhood. Eliza’s stepfather, while he adored her, felt that she was growing up wild in India and decided to send her back to live with his relatives in Scotland. The contrast between the heat and lush climate of India and the harsh winters of Scotland must have been a shock to the little girl, who had been abandoned first by her father’s death and now by her mother and stepfather. She became rebellious and chafed against life in a small town. “The queer, wayward Indian girl,” as Eliza was known, once scandalized the town by running down the street naked.

There was a short stint in a boarding school in Bath, until her mother came to England to whisk her back to India to marry her to a “rich and gouty old gentleman of 60 years,” as she put it in her memoirs. Looking for a way out, Eliza eloped instead with Lieutenant Thomas James, an army officer on leave from India. Eliza quickly realized that she had jumped out of the frying pan into the fire. Eliza had known very little about her husband before they eloped. She claimed that he started to drink heavily and to slap her around. She returned to India with him, but the marriage was doomed. In 1842, he either abandoned her for another woman or she left him when she couldn’t take his violence and infidelity anymore. Shunned by her mother for bringing disgrace to the family, Eliza sailed to England to live with her stepuncle. She never made it.

During the long journey home, Eliza carried on a scandalous shipboard romance with a dashing army officer named Charles Lennox. When they arrived in London, they continued their affair and Lennox introduced her to several influential men. When word of their affair reached her husband, he filed for divorce, citing her adultery with Lennox. Unfortunately Lennox proved no better than her husband. He dumped her with no means of support. Only twenty, Eliza had already caused multiple scandals through a failed marriage, elopement, and adultery. What was a girl with few skills to do? Why, go on the stage, of course!

With no talent for acting, she decided to become a dancer. Too old now to launch a ballet career, Eliza headed for Spain for six months to learn flamenco and Spanish. When she arrived back in London she was no longer Eliza Gilbert James but Maria Dolores de Porris y Montez, “the proud and beautiful daughter of a noble Spanish family.” Lola Montez was born.

Lola was engaged to perform at Her Majesty’s Theatre, where her debut was a great success, but it was revealed in the papers that she was a fraud. Her contract was subsequently canceled by management. Lola later claimed that London audiences were incapable of appreciating the subtle quality of her dancing.

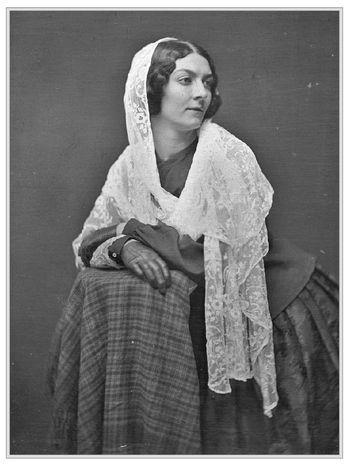

The truth was, Lola sucked as a dancer. She had no sense of rhythm or timing, and all her dances had a tendency to look alike; but at the same time she knew how to work that spotlight. She wore a costume of a black lace dress with a high collar, the better to frame her face and her magnificent bosom, with a decoration of red roses. She had the advantage of being beautiful, with lustrous dark hair, ivory skin, and stunning blue eyes. Her most famous dance, the Tarantula, consisted of Lola conducting a frenzied search of her person for the elusive spider. Inevitably she would reveal a great deal of leg, shocking the audience. The secret of her success was that she was utterly shameless. Audiences either loved or hated her.

Lola decided to take her act on the road, where she danced and caused scenes wherever she went. She was like a beautiful untamed animal who believed that the rules didn’t apply to her. Try to keep her out of the royal enclosure when Russia’s tsar is in town? A policeman was struck in the face with Lola’s riding crop in Berlin when he tried that. Try to take liberties? Well, a man might find himself stabbed, as one unwanted suitor found out in Warsaw. Hissing during one of her performances meant one felt the lash of Lola’s tongue, as she berated the audience.

Noticing that Franz Liszt was performing in Berlin, Lola decided that he would be her next conquest. When Lola aimed, she aimed high. What Byron was to poetry, Liszt was to classical music, a Victorian rock star. He’d already cut a swath through the women of Europe, who threw themselves at him, and he had a longtime mistress, by whom he’d had three children, when he met Lola. The love affair lasted a week but Lola dined out on the story for years.

It was in Bavaria that Lola would pass into history as legend. After auditioning for the State Theatre, Lola was told by the theater’s manager her dancing might cause moral offense. Lola stormed the palace unannounced to plead with the king himself for help. When the king asked her if her bosoms were real, Lola grabbed a pair of scissors and cut open her bodice, revealing her magnificent breasts. Whether or not this is what really happened, Lola got her wish. Ludwig, a Hispanophile, was defenseless against her “Latin” charms. Her career on the Munich stage lasted a scant two performances. The sexagenarian monarch became smitten by Lola, and the dancer enjoyed a new role—as his mistress.

Within weeks she had a powerful hold over Ludwig. She agreed to sit for a portrait, which would be included in Ludwig’s renowned Gallery of Beauties. During her sittings, Ludwig would join her, spending the time getting to know her. He wrote reams of bad love poetry extolling her beauty. Soon the king remodeled a stately home for her, spending millions of dollars along the way. Lola quickly announced her retirement from the stage after a career that encompassed less than two dozen performances in four years.

The affair was an international sensation, selling papers in England and France, where they reported that mobs were rioting in Bavaria and disclosed Lola’s sordid past. Lola openly boasted about her relationship with the king, although later in life she claimed that the relationship was strictly platonic. Perfecting the art of the tease, she indulged his foot fetish, letting him kiss and suck her toes. Ludwig’s advisers, friends, and family warned him that Lola was nothing but an adventuress, but the more they tried to persuade him, the more stubborn he became. He refused to believe what he considered to be lies about his Lola. Lola, convinced of her own nobility, wanted a title of her own. Ludwig obliged by making her Countess of Landsfeld, despite the fact that only Bavarian citizens could be ennobled, and the Council of Ministers refused to grant Lola citizenship.

Lola hungered for social acceptance from the nobility in Munich but it was not forthcoming. If she had been more diplomatic, like Louis XV’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour, coating her requests with sweet nothings and a pleasing disposition, things might have been different, and her reign as Ludwig’s mistress might not have ended in disaster.

Other books

A Faire in Paradise by Tianna Xander

Captured by Desire by Donna Grant

Bike Curious (Black Phoenix MC) by Knowles, Tamara

Beautiful Child by Torey Hayden

Rhuddlan by Nancy Gebel

Becoming Death by Melissa Brown

Prisoner's Base by Rex Stout

Bashert by Gale Stanley

How's the Pain? by Pascal Garnier

Broken Butterflies by Stephens, Shadow