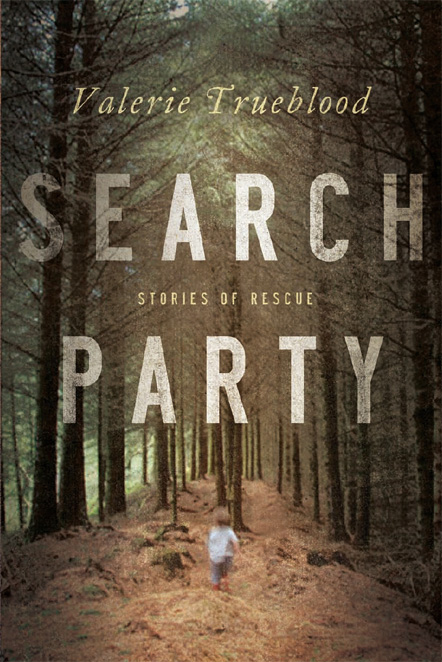

Search Party

Authors: Valerie Trueblood

Valerie Trueblood

STORIES OF RESCUE

PARTY

COUNTERPOINT PRESS

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

Copyright © 2013 Valerie Trueblood

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The author thanks the publications where some of these stories first appeared:

One Story

, “The Magic Pebble”;

Wordsmitten

, “Street of Dreams”;

Thresholds

(

UK

), “The Llamas”;

Seattle Review

, “The Finding.”

These stories are works of fiction. The events and characters in them are products of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual events or to persons living or dead is coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Trueblood, Valerie.

[Short stories. Selections]

Search party : stories / Valerie Trueblood.

pages cm

“Distributed by Publishers Group West”âT.p. verso.

ISBN

978-1-61902-223-2

I. Title.

PS

3620.

R

84

S

43 2013

813'.6âdc23

Â

2013002369

Cover design by Faceout Studios

Interior design by David Bullen

Counterpoint Press

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10

Â

9

Â

8

Â

7

Â

6

Â

5

Â

4

Â

3

Â

2

Â

1

He said, “If a story begins with finding,

it must end with searching.”

Penelope Fitzgerald,

The Blue Flower

STORIES OF RESCUE

PARTY

T

HIS

is how my new life came about.

It started with symptoms I thought might be neurological. As a nurse, I was alert to a new unfamiliarity in the way things looked, as if I kept finding myself on the wrong street, or as if I were traveling abroad. The stores of what was ordinary enough to be ignorable seemed to be shrinking. Sometimes I seemed to inhabit my body the way you stand on a foot that has been asleep.

It may be that the organs attempt, in a language we do not know, to give us tidings of their dim world. Or with secret promptings they may impel us to ends of their own.

I had never visited this practice before, but I had worked in the same hospital with the neurologist long ago. He had been someone I knew to say hello to, a well-liked man, a good doctor, married, though without children and said to be unlucky in his home life.

On the morning of my appointment I got up and looked out at the rain. Water was materializing on the windowsill, filmy and soundless. It was December so I put on a red sweater over my uniform. I took a bus from work in the afternoon, and in the neurologist's waiting room, which was empty, I sat up straight to give the nurse the understanding that I was not demoralized by the winter rains of our city, the slow or the steady, or the short daylight. I was not a depressed woman drawing myself up to the

radiator of a doctor's attention. If anything I was unnaturally cheerful. I wanted to seize whole tortes from cabinets in the bakery, and bottles of wine from under people's arms, and sofas out of window displays, that I had no room for in my small house.

In the clinic, there was no one in sight except the short young girl with a triangular face at the desk behind the glass, who had slid me a clipboard of forms with her bitten fingernails. When she saw me looking at her half-inch-long hair she turned away and touched it with her fingers. Well, hair is that short! I thought. Where have I been?

After a few minutes she looked up sharply and said, “Just go through the door. Room three.”

From the hallway came a heavy sigh, a groan, actually, just before the doctor knocked. Then his voice, very deepâI remembered the voiceâsounded from the door. “My nurse is not here,” he said. “In a moment Angelique will come in so that I can examine you.” He was fifty or so now, with big pale flap ears, and neatly dressed, tall but not erect. He had the stoop of a person with a bad back, and the eyes in folds that I recalled from seeing him in the hospital years ago. Now that I was older I knew these were drinker's eyes. “My nurse called and said she would not be in. She quit. No notice. There are no charts set out, as you see. No X-rays. She simply quit.” He appeared only half able to think, like a man who has been up all night.

“I am a nurse,” I said, waiting for him to recognize me, although I had been younger and prettier at the time I worked in that hospital.

“I see that,” he said, scanning the clipboard.

“I used to work down the hall from you at the university,” I said, pointing to my name on the form, and then to my employer's name, to let him know I was not in search of a job.

“Is that so?” he said.

Angelique opened the door without knocking. “What if the phone rings while I'm in here?” she demanded, putting her foot in the wastebasket to stomp down its contents.

“We might empty that,” the doctor said, avoiding her gaze.

She ignored him. Hey there! I signaled him with an older-generation smile. Better establish some authority with this girl!

She did get down in front of the examining table and grapple on her knees with a step, which she yanked out for me to mount. I settled myself on the padded table surrounded with metal trees holding instruments. “If you're not going to have her

disrobe

,” said Angelique, “I don't need to be here, do I?” and she went out, shutting the door firmly behind her.

The man looked blankly at the ophthalmoscope in his hand. Finally he switched it on and began to peer at my retinas, changing his angle minutely again and again, and breathing as if his belt were too tight. After a while he said, “I am going to have to dilate your eyes. I have not been brought up to date on your problems.” He glanced at my forms. “You are a new patient. And you were not referred.”

“No,” I said. “I came straight to you.”

“Headache,” he said wearily.

“No,” I said. I described my symptoms while he put drops in my eyes. After a while he hunched over them again. At length I submitted half-blind to all the tests with pin and hammer, of reflex, balance, strength, and mentation, naming the year, the city where we lived, the president. It was at the mention of the president that our eyes met. This was some years ago. I could tell we felt the same despairing way about the man. “I am going to ask you to have an MRI. There is only one real finding, and it may be nothing. But we will take a look.” He stood up and pressed his wide waist, stifling a deep, trembling yawn.

“I agree,” I said. It was not like me not to ask what the finding was.

“Are you planning to stay?” he asked Angelique rather cautiously as we passed her cubicle.

“I have to study my Spanish. You don't remember, but my exam is tonight, so there's no point in going home. So I'll close up!” She swiveled the chair so her back was to us.

“Well, then. I will leave now,” he said, “to pick up some things. Good night.”

It was dusk but the sun had come out, producing that low-lying light that seems to be coming from below rather than above. The air was full of water. You could hear water slipping over the edges of the grates in the parking lot. On the steps he said, “Now I remember you. Urology.”

“Cardiology,” I said.

“Well, I have business to attend to.” He smiled unpleasantly, as if I had detained him. “My wife, soon to be my ex-wife, has my dog. I am going to get her. The dog.” He searched his pockets.

“Where does your wife live?” I said.

“Where indeed. In

her

house by the lake.”

“I wonder if you could give me a ride. I can't see. I do have a car, but I came on the bus. I ride the bus when I want to think.”

“Well, if you have left off thinking for the day,” he said, opening the door of his car. He performed a tight turn to get out of the parking lot, with the tires splashing.

I did not get out at the corner where I could have walked home; I had decided not to. Instead I asked him about the dog. This worked a change in him; his face lit up with malice. He began to talk. His wife was bent, it seemed, on punishing faults in him that he did not name, and would not give him his dog, even though she disliked dogs and had not the slightest notion how to take care of them. She might have changed the locks to keep him out. She thought he wanted to get into the house and make off with things he had bought for her, when in fact he was perfectly happy to have left everything behind; he didn't care even to go near the house again, except for the dog. The dog was his. His deep voice had become a snarl; he shook his shoulders and said, “Where exactly may I drop you off?”