Seven Dirty Words (19 page)

Though its origins were benign, WBAI had developed a reputation for probing the issues of tolerance and provocation. A well-to-do New Yorker named Louis Schweitzer purchased the station in the mid-1950s as a pet project—he wanted to hear more classical music on the radio. The station began turning its first profit by the end of the decade, when it attracted new listeners seeking news and information during a newspaper strike. Schweitzer quickly grew discouraged by the amount of advertising required to make a commercial radio station profitable, and he decided to give it away. He contacted Harold Winkler, the president of the Pacifica Foundation, operator of the first listener-supported station in the country, Berkeley’s KPFA, and a sister station, KPFK, in Los Angeles. Assuring Winkler he wasn’t a crackpot, Schweitzer convinced Pacifica to take over the station.

WBAI began establishing its own identity when the radio novice Bob Fass urged the new owners to let him try out the after-hours show that became

Radio Unnameable

. “He played all kinds of records; he interviewed all kinds of people,” writes the author of a history of alternative radio. “He allowed musicians to jam, live, in the studio; he did news reports, took listener calls, and sometimes, his colleague Steve Post recalls, simply rambled, ‘free-associating from the innards of his complex mind.’ Fass also pioneered the art of sound collage: He was surely the first DJ, and perhaps the last, to play a Hitler speech with a Buddhist chant in the background.”

As the sixties progressed, WBAI became a well-known staging ground for liberal thinking in the New York area. The station’s Vietnam coverage was groundbreaking, as was its reporting on the civil rights movement. Paul Krassner, a regular participant whose voice was doubtless familiar to listeners of Fass and Post’s eccentric shows, once pretended to be a Columbia University student “liberating” Post’s time slot during the occupation of the university by students.

About a month after Gorman broadcast the Carlin routine, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) received a complaint from a Manhattan man named John H. Douglas. The correspondent alleged that he had been driving in his car with his son—some accounts claim the boy was twelve at the time, others, fifteen—when they heard Carlin’s “Filthy Words.” “Whereas I can perhaps understand an X-rated phonograph record’s being sold for private use,” Douglas wrote, “I certainly cannot understand the broadcast of same over the air that supposedly you control. Any child could have been turning the dial, and tuned in to that garbage.” He had recently read about the FCC fining a radio station for a sexually suggestive call-in discussion program, he wrote. “If you fine for suggestions,” Douglas asked, “should not this station lose its license entirely for such blatant disregard for the public ownership of the airwaves?” The complainant was said to be a minister and a member of the planning board of an organization called Morality in Media, to which he sent a copy of his letter.

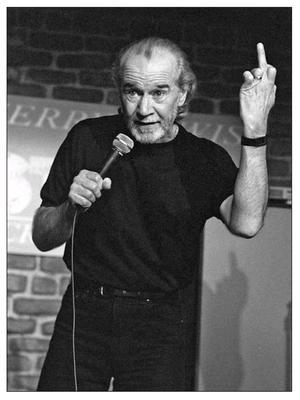

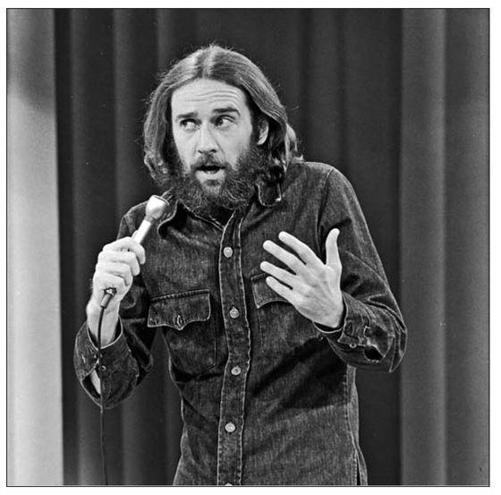

George Carlin, comedian.

© Michael Ochs Archives/ Getty Images

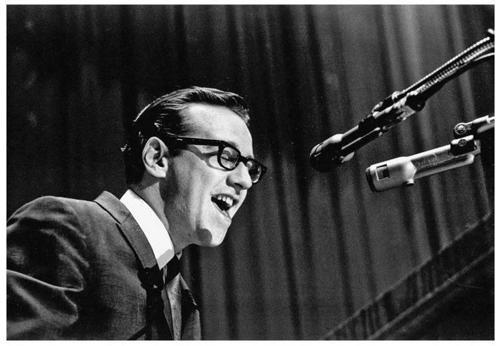

“Bing bong, five minutes past the big hour of five o’clock!”

Courtesy of Photofest NYC

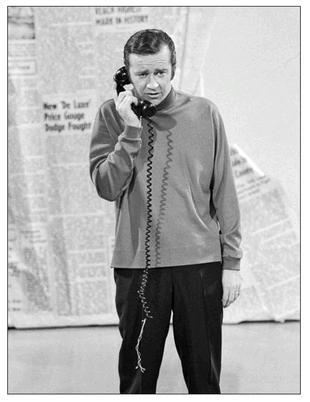

Clowning with Buddy Greco on

Away We Go

, 1967.

© Everett Collection/Rex Features

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour

, 1969.

© CBS/Landov

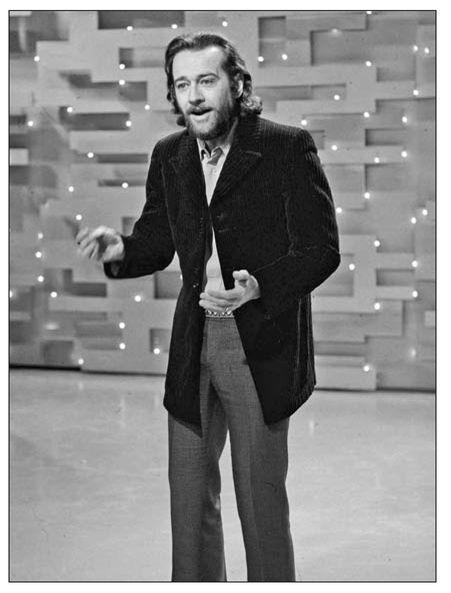

Unveiling “The Hair Piece” on

The Ed Sullivan Show

, 1971.

© CBS/Landov

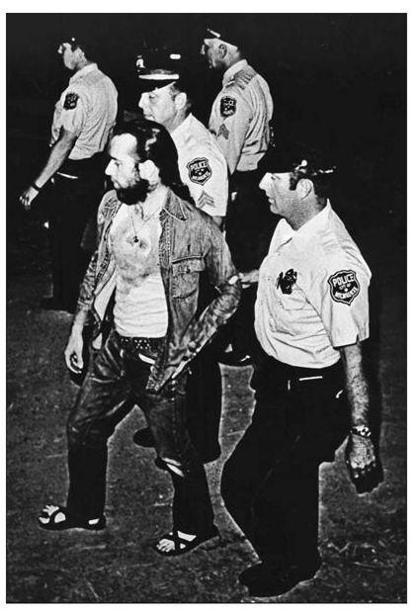

Milwaukee bust, 1972.

© Associated Press

Sticking it to the Man.

© Hulton Archive/Getty Images

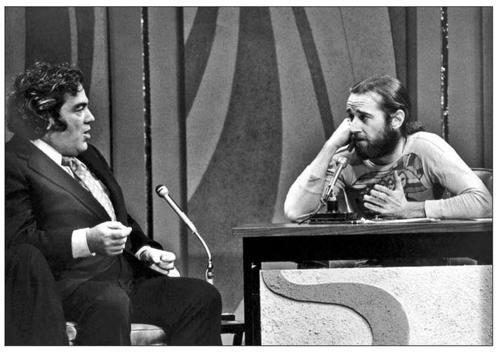

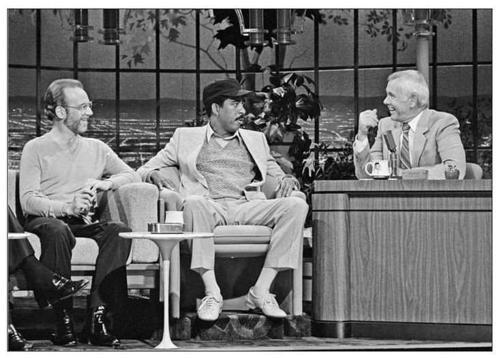

Manning the

Tonight Show

desk with guest Jimmy Breslin, 1974.

© Everett Collection/Rex Features

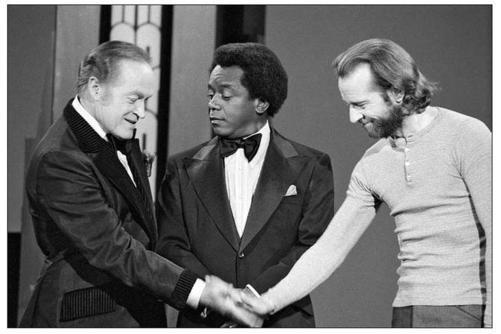

Bridging the generation gap: with Bob Hope and Flip Wilson, 1975.

© CBS/Landov

Discussing the Comedian Health Sweepstakes with Richard Pryor on Carson’s show, 1981.

© Associated Press

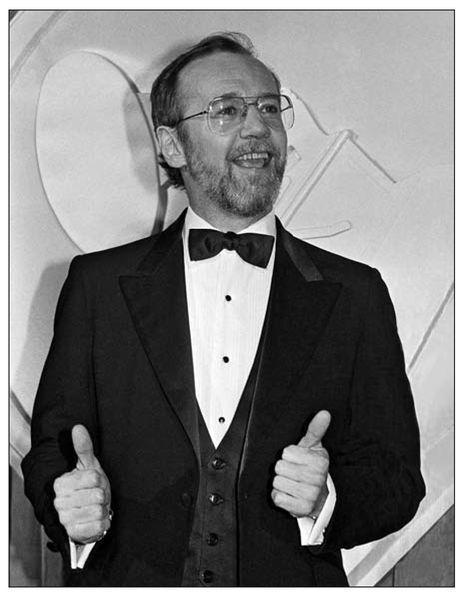

In a rare penguin suit at the Grammy Awards, 1982.

© Associated Press