Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree (36 page)

Read Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree Online

Authors: Tariq Ali

I have been thinking of you a great deal over the last few days and I wish we had spoken more to each other when we lived in the same house. I will confess to you that one part of me wanted to come to Fes with the old man. To see you and Ibn Daud. To watch you bear children, and to be their uncle. To begin a new life away from the tortures and deaths which have taken over this peninsula. And yet there is another part of me which says that I cannot desert my comrades in the midst of these horrors. They rely on me. Mother and you always thought that I was weak-willed, readily convinced of anything and incapable of firmness. You were probably right, but I think I have changed a great deal. Because the others depend on me I have to wear a mask, and this mask has become so much a part of me that it is difficult to tell which is my real face.

I will return to the al-Pujarras, where we control dozens of villages and where we live as we used to before the Reconquest. Abu Zaid al-Ma’ari, an old man you would like very much, is convinced that they will not let us live here for much longer. He says that it is not the conversion of our souls which they desire, but our wealth, and that the only way they can take over our lands is by obliterating us forever. If he is correct then we are doomed to extinction whatever we do. In the meanwhile we will carry on fighting. I am sending you all the papers of our old al-Zindiq. Look after them well and let me know what Ibn Daud thinks of their contents.

If you want to reach me, and I insist you let me know when your first child is born, the best way is to send a message to our uncle in Gharnata. And one more thing, Hind. I know that from now till I die, I will weep for my dead brother and our parents every day. No mask I wear can change that in me.

Your brother,

Zuhayr.

The Dwarf had not been able to sleep for more than a couple of hours. When dawn finally came he rose and left the room for his ablutions. When he returned, Zuhayr was sitting up in bed, looking at the morning light coming through the window.

‘Peace be upon you, old friend.’

The Dwarf looked at him in horror. Overnight, Zuhayr’s hair had turned white. Nothing was said. Zuhayr had noticed the box containing Yazid’s chess pieces amongst the Dwarfs belongings.

‘He left them with me when he went up to see if he could find the Lady Zubayda.’ The Dwarf began to weep. ‘I thought the Lady Hind might like them for her children.’

Zuhayr smiled, biting back the tears.

An hour later, the Dwarf had embarked on a merchant vessel. Zuhayr was on the shore, waving farewell.

‘Allah protect you, Zuhayr al-Fahl!’ the Dwarf shouted in his old voice.

‘He never does,’ Zuhayr told himself.

T

WENTY YEARS LATER, THE

victor of al-Hudayl, now at the height of his powers and universally regarded as one of the most experienced military leaders of the Catholic kingdom of Spain, disembarked from his battleship on a shore thousands of miles away from his native land. He strapped on the old helmet which he had never changed, though he had been presented with two made from pure silver. In addition, he now wore a beard, whose redness was the cause of many a ribald jest. His two aides, now captains in their own right, had accompanied him on this mission.

The expedition travelled for many weeks through marshes and thick forests. When he reached his destination, the captain was greeted by ambassadors of the local ruler, attired in robes of the most unexpected colours. Gifts were exchanged. Then he was escorted to the palace of the king.

The city was built on water. Not even in his dreams had the captain imagined it could be anything like this. Boats ferried people from one part of the city to another.

‘Do you know what they call this remarkable place?’ he asked, to test his aide, as the boat carrying them docked at the palace.

‘Tenochtitlan is the name of the city and Moctezuma is the king.’

‘Much wealth went into its construction,’ said the captain.

‘They are a very rich nation, Captain Cortes,’ came the reply.

The captain smiled.

| Abu | Father |

| Ama | Nurse |

| al-Andalus | Moorish Spain |

| al-Hama | Alhama |

| al-Hamra | the Alhambra |

| al-Jazira | Algeciras |

| al-Mariya | Almeria |

| al-Qahira | Cairo |

| bab | gate |

| Balansiya | Valencia |

| Dimashk | Damascus |

| faqih | religious scholars or experts |

| funduq | hostels for travelling merchants |

| Gharnata | Granada |

| hadith | sayings of the Prophet Mohammed |

| hammam | public baths |

| Iblis | devil; leader of the fallen angels |

| Ishbiliya | Seville |

| Iskanderiya | Alexandria |

| jihad | holy war |

| Kashtalla | Castile |

| khutba | Friday sermon |

| madresseh | religious schools |

| Malaka | Malaga |

| maristan | hospital/asylum for the sick and the insane |

| qadi | magistrate |

| Qurtuba | Cordoba |

| riwaq | students’ quarters |

| Rumi | Roman |

| Sarakusta | Zaragoza |

| Tanja | Tangier |

| Tulaytula | Toledo |

| Ummi | Mother |

| zajal | popular strophic poems composed impromptu in the colloquial Arabic of al-Andalus and handed down orally since the tenth century |

Tariq Ali is a novelist, journalist, and filmmaker. His many books include

The Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity

;

Bush in Babylon: The Recolonization of Iraq

;

Conversations with Edward Said

;

Street Fighting Years: An Autobiography of the Sixties

; and the novels of the Islam Quintet. He is the coauthor of

On History: Tariq Ali and Oliver Stone in Conversation

and an editor of the

New Left Review

, and he writes for the

London Review of Books

and the

Guardian

. Ali lives in London.

Turn the page to continue reading from the Islam Quintet

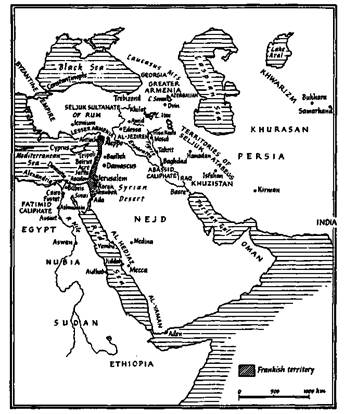

The Near East in the late twelfth century

A

NY FICTIONAL RECONSTRUCTION OF t

he life of a historical figure poses a problem for the writer. Should actual historical evidence be disregarded in the interests of a good story? I think not. In fact the more one explores the imagined inner life of the characters, the more important it becomes to remain loyal to historical facts and events, even in the case of the Crusades, where Christian and Muslim chroniclers often provided different interpretations of what actually happened.

The fall of Jerusalem to the First Crusade in 1099 stunned the world of Islam, which was at the peak of its achievements. Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad were large cities with a combined population of over two million—advanced urban civilisation at a time when the citizens of London and Paris numbered less than fifty thousand in each case. The Caliph in Baghdad was shaken by the ease with which the barbarian tide had overwhelmed the armies of Islam. It was to be a long occupation.

Salah al-Din (Saladin to Western ears) was the Kurdish warrior who regained Jerusalem in 1187. The principal male characters of this story are based on historical personages. They include Salah al-Din himself, his brothers, father, uncle and nephews. Ibn Maymun is the great Jewish physician-philosopher, Maimonides. The narrator and Shadhi are my creations, for whom I accept full responsibility.

The women—Jamila, Halima and all the others—have all been imagined. Women are a subject on which medieval history is usually silent. Salah al-Din, we are told, had sixteen sons, but nothing has been written about their sisters or mothers.

The Caliph was the spiritual and temporal ruler during the early days of Islam. He was elected by acclamation by the early Companions of the Prophet. Factional disputes within Islam led to rival claims, and the birth of the Shiite tendency split the political heirs of Mohammed. The Sunni Muslims acknowledged the Caliph in Baghdad, but civil war and Shiite successes led to the establishment of a Fatimid Caliph in Cairo, while the Sunni faction displaced by the Abbasids reached its zenith by establishing a Caliphate in Cordoba in Muslim Spain.

Salah al-Din’s victory in Egypt led to the dissolution of the Fatimid dynasty and brought the entire Arab region under the nominal sovereignty of the Caliph of Baghdad. Salah al-Din was appointed Sultan (King) of Syria and Egypt and became the most powerful leader of the medieval Arab world. The Caliphate in Baghdad was finally destroyed by Mongol armies in 1258, and ceased to exist until its revival in Ottoman Turkey.

Tariq Ali

June 1998

One

On the recommendation of Ibn Maymun, I become the Sultan’s trusted scribe

I

HAVE NOT THOUGHT

of our old home for many years. It is a long time now since the fire. My house, my wife, my daughter, my two-year-old grandson—all trapped inside like caged animals. If fate had not willed otherwise, I too would have been reduced to ashes. How often have I wished that I could have been there to share the agony.

These are painful memories. I keep them submerged. Yet today, as I begin to write this story, the image of that domed room where everything once began is strong in me again. The caves of our memory are extraordinary. Things that are long forgotten remain hidden in dark corners, suddenly to emerge into the light. I can see everything now. It comes to my mind clearly, as if time itself had stopped still.

It was a cold night of the Cairo winter, in the year 1181 according to the Christian calendar. The mewing of cats was the only noise from the street outside. Rabbi Musa ibn Maymun, an old friend of our family as well as its self-appointed physician, had arrived at my house on his way back from attending to the Kadi al-Fadil, who had been indisposed for several days.

We had finished eating and were sipping our mint tea in silence, surrounded by thick, multi-coloured woollen rugs, strewn with cushions covered in silk and satin. A large round brazier, filled with charcoal, glowed in the centre of the room, giving off gentle waves of heat. Reclining on the floor, we could see the reflection of the fire in the dome above, making it appear as if the night sky itself were alight.

I was reflecting on our earlier conversation. My friend had revealed an angry and bitter side, which had both surprised and reassured me. Our saint was human just like anyone else. The mask was intended for outsiders. We had been discussing the circumstances which had compelled Ibn Maymun to flee Andalus and to start on his long fifteen-year journey from Cordoba to Cairo. Ten of those years had been spent in the Maghrebian city of Fez. There the whole family had been obliged to pretend that they were followers of the Prophet of Islam. Ibn Maymun was angered at the memory. It was the deception that annoyed him. Dissembling went against his instincts.

I had never heard him talk in this fashion before. I noticed the transformation that came over him. His eyes were gleaming as he spoke, his hand clenched into a fist. I wondered whether it was this experience that had aroused his worries about religion, especially about a religion in power, a faith imposed at the point of a sword. I broke the silence.