Shame of Man (15 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

CHAPTER 7

DREAM

Mankind was physically modern when he emerged from the water to reconquer the land, but not yet mentally modern. One of the greatest mysteries of human evolution is what happened about 40,000 years ago. During the prior hundred thousand years or so mankind shared the world with other variants of Erect man, such as Archaic man in Asia and Neandertal man in Europe, and his life-style seemed similar. Then abruptly he made dramatic advances in organization, technology, language, and all the arts, and took over the world. The prior Geodyssey volume,

Isle of Woman,

assumes that when a group of children were raised together, instead of individually by their mothers, they learned a new

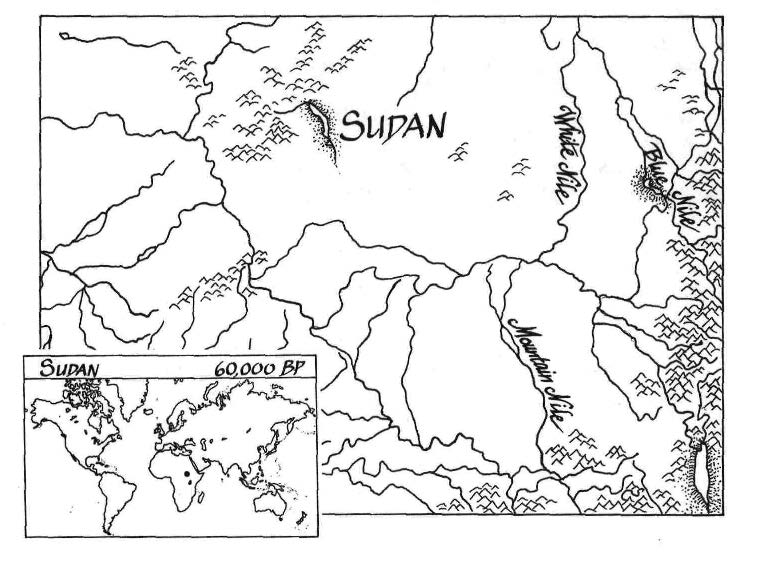

way of organizing their vocabulary, using superior syntax, and actually changed the organization of their brains in the process. Thus the origin of mankind's modern mind may have been in the Levant. That may be so, but this sequel volume assumes that it was more complicated than that, and developed more slowly in another region: Eden, or the Lake Victoria basin. That the intellectual breakthrough derives from the same place as the physical one, and followed naturally from it. That we owe our minds as well as our bodies to man's one-time adaptation to life in the water. And to our dreams. But to clarify this, we need to examine the nature of modern thinking and dreaming and memory. Much is not what it seems.The setting this time is not Eden, however. It is near the confluence of the Mountain Nile and the White Nile rivers in modern-day Sudan, about 600 miles north of Lake Victoria. The time is about 60,000 years ago. Because if this supposition is correct, the delay in the advance of modern mankind across Eurasia was not because of the resistance of Archaic man or Neandertal man, but because the giant Sahara Desert of Africa prevented the new thinking from reaching the fringe. Only very slowly could modern-minded man penetrate that vast hostile barrier, following the thin avenue of the great river where hunting and foraging remained good. It was slow because of the hostile primitive-mind modern-body tribes settled along that avenue; they would not let strangers by without trouble, and the terrain did not allow large-scale migration or invasion. The advantage that would enable mankind to explosively conquer the world may not have been enough for very small groups to prevail against set, conservative primitive cultures. Intruders had to accommodate themselves in whatever way they could, and most may have died. But some may have been lucky, and achieved a foothold. Only when their numbers increased in the world beyond the Sahara so that they could form complete communities, did the apparent transformation occur.

H

UGH walked beside the river, reflecting on his situation as he watched for suitable prey to hunt. He realized now that Bub had done it. Bub had wanted Hugh to join his tribe, and take Bub's sister Sis as a mate, but Hugh had declined and married Anne instead. So Bub had bided his time, then struck. He had been maliciously cunning, waiting until a bad storm had destroyed much of the encampment and killed several people. Then he had told Chief Joe that this was the punishment of the spirits, because the tribe harbored one who was not properly a man. One who was a reverse man.

Joe would not have accepted the word of an outsider whose tribe was at times hostile, but it was a time of stress, and Bub offered to bring his tribe to join in a larger hunt that would bring in enough meat to support both tribes until the situation recovered. Bil had not liked it, but had recognized that a joint hunt would indeed be mutually profitable; it made sense. So he and

Joe considered it, while the privation continued and the people grew leaner. Bub refused to hunt with Hue, because of that bad hand. Bub's well-formed sister circulated, having private liaisons with men, and in her wake the hostility to wrong-sidedness grew. Hue came to understand, belatedly, that he had angered Sis by his refusal to marry her, and though men governed the tribes, the mischief of a woman disdained could be formidable.

No one before had remarked upon Hugh's preferred use of his left hand to wield his axe. Now the attention of the tribe focused on it, and others were too ready to believe that this was indeed the malice of the spirits. Hugh was one of the leaders of the tribe, but his position eroded, and soon he was unwelcome. Anne supported him, refusing to desert him for another man, though she used her right hand. Thus she too became suspect. Indeed, she had suffered a difficult childbearing, almost dying; now this too was brought forth as evidence of the mischief of bearing the baby of a cursed man. She had recovered and was now fully healthy, but the shadow remained.

“It isn't that we think you are bad,” Joe explained, embarrassed. “But we dare not go against the spirits. If they strike again . . .”

That hardly mattered now. Hugh and Anne had had to leave with their baby son Chip, exiled. Anne had been devastated by the thought of leaving her tribe, but then had rallied and realized that she no longer needed the tribe, now that she had a family. They had fled down the great river, because that was the only direction that offered some hope of forage. There were always fish in the river, and if there were also more formidable creatures, these could be avoided. The plants by the riverside were lush, and of course there was always good water to drink. And there were inevitably people, eventually, for others also appreciated the advantages of water.

Unfortunately people represented one of the greatest dangers, because many tribes simply killed any strangers who intruded on their territories. So Hugh looked as carefully for signs of people as for animals and plants. He wanted to spy before being spied on. His life could depend on it.

The vegetation became tangled, and the water crossed rapids, which would be dangerous to enter, so he moved out somewhat, rounding the curve of a hilly slope. Then he stopped, because he heard something ahead. He remained quite still for a moment, holding his breath, orienting on the sound. Then he moved quietly behind a tree: one that would be easy to climb if necessary.

The sound seemed to be retreating. Whatever it was was moving away. Therefore it represented no immediate threat. It was probably some kind of antelope, a beest, too big and fast for a man alone to hunt. Hugh relaxed. There were many such false alarms in the course of an exploration or hunt,

and each had to be taken seriously, because any one of them just might turn out to be lethally true.

By the time he skirted the thicket crowding the river he was in a ravine leading away from both the river and his camp. He picked his way to the clearest avenue to get back on course, climbing a steep slope. It was as if the animal had led him astray, or perhaps driven him off his original path. Or as if he were fleeing some horror of the valley, ascending the mountain, looking for food and safety. As indeed he was, in a larger sense.

He crested the rim of the ravine, and spied a rabbit perched near, its ears alert. He hefted his axe, conscious now as not before that it was his left hand that held it. But as he drew back his arm to throw, the rabbit bounded away. He followed it, mildly annoyed that he had not been alert for this. He should have crested the rim with his weapon ready to throw, and knocked off the rabbit the instant he saw it. But this was new terrain to him, and he didn't yet know the rabbit trails. One thing the episode demonstrated: rabbits in this region were not used to being hunted by man. That suggested that this would be a good place to remain for a while.

He pursued the rabbit, carefully, also watching for other creatures. How many men had been led to their deaths by focusing too narrowly on a hunt when in strange terrain? He could not afford to come to mischief, because Anne depended on him. She was more than competent, but she had their baby to care for, and needed his support.

Then the rabbit paused again, thinking it was out of sight. Hugh heaved his axe. The rabbit heard it coming and tried to jump out of the way, but the blade caught it flatside and knocked it unconscious. He closed on it immediately, picked it up, and checked: it was dead. Good enough. Now he could return to camp.

He put the rabbit in his game pouch, wiped off his axe, and angled for the river, whose voice he could hear not far distant. But as he crested another ridge he saw a distant plume of smoke. He stopped again, orienting on it much as he had on the animal sound. How far was it, and how big? Was it a distant volcano, or a near camp fire? Or an intermediate brush fire? All three were dangerous in their own ways. But as a general rule, the farther away it was, the safer it was.

He concluded that it was an intermediate fire, not big enough for brush, so probably a tribal campsite. He made careful note of its location; he would avoid that until he had no choice. When he encountered the people of this region—and the fire made it clear that they existed—he wanted to do so in a planned manner, with a good escape route planned. But he might be able to avoid such contact for some time, since they evidently didn't often hunt here. Now that he knew where they were.

Hugh resumed his quest for the river. He saw movement in the thicket. In a moment he identified it as a monkey. He could probably strike it with his

axe, as it was regarding him curiously from what it thought was a safely high vantage. Monkeys, too, had not been hunted here recently. But he already had his kill, and there was something about its almost manlike aspect that made him disinclined to hurt it anyway. Monkeys were not men, yet they were not really far different from men, and the similarity bothered him a bit. Other men had regarded this qualm on his part as foolish, but it remained. He would not kill a monkey unless he had to.

He moved on, and soon saw the river, or rather the spray of water and mist it threw up at the foot of its rapids. As he come closer he felt the fringe of that spray like a light rain on his face, hands, and arms. He saw that the lay of the land was such that he would do better to cross to the other side of the river here rather than farther down where it might be deeper; there were rocky shallows here that he could navigate readily enough, with several channels running between them. He made his way down to the water.

There was motion on the near bank. Hugh stood still, his arm cocked, his eyes searching. It was a little crocodile, harmless and shy as far as he was concerned, though dangerous to smaller creatures. This was another creature he could have killed for food, if he had not already gotten his rabbit. This was truly a good hunting ground.

He used his axe to cut a sapling for a staff and made his way across the river, carefully, checking each rock before trusting his weight to it. He jumped across the surging channels after poking the landing sites with the end of his staff. It wasn't just firmness he checked for, but to make sure there were no bad snakes or bugs by them. One bad sting on a foot could be much mischief. He got soaked by the spume, at times plowing a seeming rainstorm, but that was the way of such things.

He completed his crossing, then paused to sniff the air. There was something. He searched the bank, checking every tree, sniffing repeatedly until he had it.

“Anne,” he said, facing the right tree.

She stepped out from behind it, the loveliest creature he knew. She was naked, with her dark hair swirling down around her very full bosom. “You took long enough to spot me,” she said. “If I were a man, I could have attacked you.”

“Men aren't in this region,” he replied, advancing on her. “Except farther downriver where there's a camp.”

She came to meet him, walking in the manner only she could. “Let me wash you,” she said.

He let her strip away his loin-fur and pouch and set them on the ground. Then she led him back to the nearest thick spray-channel. It was a narrow one, with the water throwing up a constant barrage of drops and splash. Sunlight slanted through the vapor, making circular rainbows.

She stepped halfway across the channel and stood with her legs spread above the surging flow, one foot on each side. “Come to me, my ardent man,” she said, smiling.

“Are you not concerned that I am wrong-handed?” he asked her, making a joke of what had become most serious. “That the spirits will strike you down for associating with me?

She answered him seriously. “I was virtually outcast myself, before you came and found me beautiful. If that was the mischief of the spirits, then I have no fear of them.” She smiled again, spreading her arms and breathing deeply, inviting him with all her body. She was more than beautiful, with her swirling hair and phenomenally full breasts and sleek body and limbs.

How could he resist? He straddled the cleft of the river, facing her, feeling the water striking his legs and crotch. He moved forward to embrace her, bending his knees just enough to get his eager member into place. Her thighs were slippery wet; he slid in readily, and climaxed immediately, while she held him close and rubbed his back with flying river water. It was as if the entire river were flowing through him and into her, providing a force and ecstasy he could hardly remember experiencing before. She kissed him, her lips smiling against his. The rapture continued after his body was spent, and he just held her and held her, loving her in the wetness of it all. What did all else matter, with her here with him like this?