Shattered (15 page)

Authors: Eric Walters

“At first nobody even noticed. It wasn't like today with mass communications and satellites and Internet and CNN,” Mrs. Watkins explained. “And when it was discovered there were so many other things going on with World War I and then there was confusion about who in fact should, or could, intervene.”

“That was a long time ago,” somebody else observed. “It was. How about the killing fields of Cambodia?”

Mrs. Watkins asked.

“Wasn't that a movie?” Kelsey asked.

“It was. A movie about the genocide in Cambodia in the seventies when the Khmer Rouge movement under the command of Pol Pot killed 1.7 million people. That was over twenty percent of the total population of the country.”

“Even that was a long time ago,” the same girl said. “It makes me feel old to realize how long ago you think that is,” Mrs. Watson said with a half-smile. “Then there was Yugoslavia. The mass graves are still being discovered today. The final account, the number of different people of different groups who were killed in that genocide, is still unknown ⦠probably never will be known. And then, most recently, there was the genocide in Rwanda. Ian, do you know anything about what happened?”

“I know the numbers,” I said. “Eight hundred thousand people were slaughtered.”

One girl gasped. Nobody else even blinked. It was like they didn't hear me or didn't believe me ⦠or didn't care.

“And do you know when that took place?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

“It happened during a one-hundred-day period in 1994.”

“That can't be right,” a boy at the back said. “We would have heard about it.”

“It did happen,” Mrs. Watkins said. “This soldierâ Jackâyou said he was there.”

I nodded my head. “He was there, but he told me it was hard even for him to believe it. He told me about people being attacked with machetes ⦠about rivers being clogged with bodies ⦠other horrible things.”

I could tell by the expressions of a couple of the girls in the front that they were upset or disgusted.

“Do we

have

to talk about this?” a girl asked.

“We don't have to talk about anything,” Mrs. Watkins said. “But please explain to me why we shouldn't talk about this?”

“Well ⦠it's just so ⦠so ⦠gross.”

“And upsetting,” another girl added.

“Maybe that's why we should talk about it,” Mrs.

Watkins said. “I remember hearing a minister say that the best thing a sermon could ever do was comfort the troubled and trouble the comfortable. I think it's important to know about the world around us ⦠the larger world beyond MTV and the mall.” She took another sip from her mug and then turned directly to me. “Ian, is this soldier a friend of the family?”

“No. I just know him.”

“How do you know him?” Mrs. Watkins persisted.

I really didn't want to answer, but I didn't have much choice. “I know him from the soup kitchen.”

“Does he do volunteer work there too?” she asked. “No ⦠he ⦠he eats there.”

“He's a street person?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

“Yeah.”

“He's a

bum

?” Jason squealed and then started to laugh. “You got all your information from a bum!”

“He lives on the street, but he's not a bum!” I snapped. “And you better shut your face right now or I'm going toâ”

Mrs. Watkins was instantly at my side as I started to get out of my seat. She stepped in front of me, heading me off.

“Nobody is calling anybody anything. I want an apology. Now!”

“I'm sorry ⦠I didn't mean nothin',” Jason mumbled. Good. Nobody was going to call Jack a bum orâ “Now your turn, Ian,” Mrs. Watkins said.

“My turn to what?” I asked.

“To apologize. Nobody is either calling somebody names

or

threatening to harm them. That's how wars, and genocide, begin.”

I mumbled an apology.

“But how does somebody go from being in the armed forces to being a street person?” a girl asked.

“That's not as far a fall as you might think. People in all walks of life can end up on the streets,” Mrs. Watkins said. “Alcoholism and mental illness don't discriminate between people. The biggest difference between those

who overcome and those who succumb isn't the person who is afflicted but the people who surround that individual ⦠the supports that allow them to heal and regain their equilibrium. Some people are just lucky enough to have somebody there to help them. You know, sometimes it only takes one person.” She took another sip from her coffee. “Does anybody know what groups Hitler targeted before the Jews?”

There was no answer.

“The mentally ill and the homeless,” she said. “They were the first people he sterilized, rounded up, and exterminated. He was allowed to get away with that so he moved on to the next group. Who knows how history would have been changed if there had been a national or international reaction, outrage? Maybe he never would have cemented his power, maybe World War II never would have happened. But who was going to object to his actions? It was just a bunch of crazy, homeless people. Maybe not worthless, but certainly worth less,” she said, echoing the phrase from the last class.

Mrs. Watkins took another sip from her bottomless cup. I wanted to say something, but I just didn't know what to say. No one else seemed to know what to say either. The whole room was deadly silent. There wasn't even the sound of shifting feet or shuffling papers. Nothing.

“Did anybody here drop off flowers in memory of Crystal?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

A half-dozen girls put up their hands. Crystal was a nine-year-old girl who had been abducted, sexually assaulted, killed, and her body dumped in a park by the

lake. It had happened half a year before. It was awful ⦠just awful. I could so clearly picture herâat least the photographs of her that had been in the papers and on the newscasts. At the spot where her body had been found people had started to drop off flowers and stuffed animals. These peopleâmost had to be strangersâcame, cried, and then left. I'd seen it on the news. It had become a virtual garden of flowers, a mountain of stuffed animals.

“Did any of you girls know Crystal?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

They all shook their heads.

“Why did you bring flowers?” she asked.

“I brought a teddy bear,” one of the girls said.

“Fine. Why did you bring

anything

?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

“I just wanted to say how sorry I was,” the teddy bear girl replied.

“Yeah, so the family would know that people cared,” added another.

“How about you, Cindy?” Mrs. Watson asked.

“I ⦠I don't really know why I did it. I just wanted to try to ⦠I don't know ⦠This is going to sound stupid.” “It won't, I'm sure. Just say it,” Mrs. Watkins said.

“I just wanted to do something kind to try to make it better,” she said.

“A small act of kindness, of goodness, to try to counter the evil that was done,” Mrs. Watkins said.

“But it wasn't like I could fix it or make it better,” Cindy said.

“You're partially right. You couldn't fix it, but you did make it a little bit better. A random act of kindness

often sends ripples that have a positive effect,” Mrs. Watkins said.

“I saw her mother being interviewed. She said she was thankful to all those people who had dropped by,” another girl said.

“I was wondering, did anybody think about giving flowers for the eight hundred thousand people who were killed in Rwanda?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

“We didn't even

know

about Rwanda,” Cindy said. “You do now. You already knew about the Holocaust and the millions killed. And I've now told you about the 1.5 million people killed in the Armenian genocide and the 1.7 million people who were victims of the Cambodia killing fields, and the tens of thousands killed in the ethnic cleansing in Yugoslavia. But you can't grieve for these countless victims because they are just a number, a number so large it can't be comprehended.” She swirled the coffee in her mug but didn't sip from it. “One death is a tragedy; a million is a statistic. Does anybody know what that means?” she asked.

“I do,” I said. “The death of Crystal is a tragedy because we know herâat least we

feel

like we know her, because we can picture her, we know about her family, we've seen her mother on the news crying. But the million people, we don't know them so we don't care about what happened to them. A million is just a number, a statistic.”

“Perfectly said, Ian. But each of those million was a living, breathing, feeling human being, each as much a person as Crystal. And as long as they remain unknown, separated from us by time or distance or situation, we don't have to know them. They

remain

a statistic.”

The entire room was so silent that I could hear the ticking of the clock hanging on the back wall.

“Does anybody know who said that?” Mrs. Watkins asked.

“You, right now,” Jeremy joked.

Mrs. Watkins let out a deep, long sigh. “Does anybody know who

originally

said it?”

It had to be like Plato or Socrates or some old-time Greek philosopher, or maybe Shakespeare, he was always saying things like that, or maybe Mark Twain orâ

“Joseph Stalin,” Mrs. Watkins said.

“Who's that?”

“He was the leader of the Communist Party in Russia. Under his orders millions upon millions of his fellow Russians were executed.” She paused. “Millions and millions. He knew enough to make sure they were only statistics.”

Thirteen

FINDING MORE INFORMATION

about the genocide had been easy. Actually, it was amazing just how much information was readily available. So much information and none of us had known anything about it.

What I was finding hard was locating information that didn't just involve numbers, facts, and figures. Eight hundred thousand people had been slaughtered. I knew the numberâthe statisticâbut I didn't know about one individual person who made up those numbers. It was just one large, faceless, anonymous black mass. How could the human mind hope to comprehend what a number that big even meant? I needed to see a picture, look into somebody's eyes the way I had looked into Crystal's eyes in those pictures in the paper. The way I could

still

look into her eyes whenever I closed my eyes or called on her memory. I needed to do this, to know something about somebody who had been killed in Rwanda. I didn't exactly understand why I needed to do this, but I did. Somehow I needed to not let them just be statistics, so here I was, back at my computer.

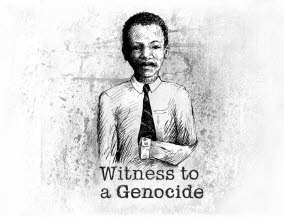

I clicked from page to page, site to site. More of the same. Maps, facts, figures, numbers, political discussion, but noâ I stopped. Staring back at me were the soft

brown eyes of a boy. He could have been ten or twelve or fourteen. I couldn't tell. He had a gentle smile and was dressed in a starched white shirt and tie and there was something wrong with his arm ⦠the sleeve was wrong. Was it just the angle of the picture or was he hiding his arm behind him or ⦠it was gone. It just wasn't there ⦠his left arm was missing. Under his picture was a title: Witness to a Genocide.

I hesitated for a second, then another. Was this what I was looking for? Now that I'd maybe found it, I wasn't sure I wanted to. I looked deep into his eyes. I knew I owed it to himâI owed it to myself to go further. I scrolled down the page. As the text was revealed at the bottom, his face disappeared from the top of the screen.

My name is Jacob. I lived in Kigali with my family. My mother and my father and my three brothers and two sisters. And in the next house lived my mother's parents and her sisters lived beside that, with all my cousins. It was April the 9th. I know the day because it was my birthday the next day. I was going to turn eleven. I was excited. I went to bed waiting for my birthday to come. I was so excited that I had trouble sleeping. My parents had trouble sleeping too but for a different reason. They were scared. I knew that. Scared of what we had heard. That people were hurting other people. Hutus harming Tutsi. My family is Tutsi. I was a little scared too, but not too much. My father and my uncles and my big cousins and my oldest brother were all around. Nobody could hurt me with them to protect me. In the night, I don't know what time, I heard the sounds on the street. Screaming and yelling but also it sounded like laughter and musicâloud music. It sounded like a party, like somebody was celebrating. And then I heard louder screaming, sounding like it was coming from right inside my house, and before I could even think the door of my room was thrown open and dark figures rushed into the room. I was grabbed by the arm and by the hair and dragged off my sleeping mat and pulled into the main room. The room was filled with people, dozens and dozens of strangers. They were yelling and screaming. Some had spears, others pieces of wood or pipe, and some had machetes. My mother was there, and my father and all my brothers and sisters. They were being held and struck! I

couldn't believe it, it was like a nightmare. We were all dragged into the street. I was punched and kicked as I was dragged along, my arm twisting and turning, my head aching, my stomach screaming out so much I thought I was going to be sick. Outside, the street was filled with even more peopleâmore people than I had ever seen. And among these strangers I saw other members of my family, my grandmother, my cousins, my uncles and aunts, all being held, and kicked, and hit with

sticks. And then I saw my grandfather, lying on the ground, not moving, his clothes painted with blood. Then I felt something, like a burning, searing pain in my arm and I looked down and my armâthe whole arm from above the elbow was gone! There was a man, holding a machete in one hand and the jagged remains of my arm in the other! I staggered backward and fell over, clasping

the stump of my arm with my other hand, the blood flowing, streaming. I tried to cry out for my mother or father when the air became filled with screams. And from the ground where I lay I saw the man, still holding my arm, waving it in the faces of my parents. My father struggled to get free and my mother cried out but they started to hit them ⦠more and more blows with fists and kicks and sticks and then my mother was struck with a machete and fell to the ground, blood gushing

from the slash across her face. I tried to get up but I was kicked and then somebody stomped on me and then something heavy, a body, tumbled on top of me. I started to struggle to move but I didn't have the strength and somehow it felt safe to be underneath, protected. I heard screams. I knew the voices. Voices of my cousins and my sisters and

my brothers crying out in pain. And along with those voices there were other people, cheering, laughing, and the sound of music kept on playing. I couldn't see, pinned beneath the body, and I closed my eyes. I knew that if I screamed or cried out for help that nobody could come to save meâit would just draw attention. My only hope to not die was to have them think that I already was dead. I felt weaker and weaker and then nothing.