Shorelines (2 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

It emerged that one Jakob Holtzhausen, a machinist who worked in the

binnekamp

(inside camp) at the mine, had become a very keen pigeon fancier and something of an avian tailor as well – he’d developed a nifty little harness he could attach onto his flying smugglers. He would take one to the diggings in his lunchbox and, when he found diamonds in the course of his work, he’d load them into the bird’s harness. You can figure out the rest. Jakob went to jail for a year. From that point onwards, pigeons were shot out of the sky over Alexander Bay.

So you can imagine the kind of reception given one rather clinically named GB S82074.99, a British homing pigeon that famously strayed off course in mid-2002, when he flew in over Alexander Bay all the way from Derbyshire, England. Old ‘GB’ had been on his way to France when he was blown down to Africa in a storm over the English Channel and arrived 8 000 km later in Alexander Bay. He was captured, presumably strip-searched and returned to his owner, Englishman Harry Sinwell.

But much as I love a diamond-smuggling story, the inner beast needed feeding.

“Look at this marvellous breakfast menu,” I exclaimed to Jules just after we’d checked into a cavernous room at the Frikkie Snyman Guest House in town. The ‘special’ involved bacon, eggs, salami, lashings of ostrich steak – and deliciously sweet West Coast oysters, if you could fit them in. She gently nudged me towards the muesli.

“OK, I was just looking,” I said, still eyeing the Richtersveld breakfast line-up. “Do you think all that comes with a lightly fried porcupine quill?”

Nearly a century ago, the breakfast specials were very different in these parts. Then it was loose-leaf tea boiled in a billy and whatever you could shoot. In

The Glamour of Prospecting,

you’re truly on the diamond trail with old Fred Cornell, one of the legends of the Richtersveld. Fred knew there was something precious and shiny up at the mouth of the Orange River. Somehow the rich finds constantly eluded him, but he stuck to his guns, lived under the stars and wrote one of the best travel books you’ll ever cast eyes on.

Imagine yourself back then in a lonely spot up on the Orange River, having a quiet smoke in the moonlight. This is about as far from civilisation as you can get. Peace reigns and you get quite sentimental about your life. Perhaps a bit nostalgic for a cold beer. The flash of a saloon girl’s eye.

Suddenly, there’s the distant sound of a concertina. You go back to the campfire to discover your travelling partner (in Fred’s case, a likeable ruffian called Ranssom) being entertained by a grinning Owambo wearing a full German colonial-army uniform, right down to elastic-sided boots with spurs, heaving away merrily at his concertina, having just appeared out of the black night as if from nowhere. With him are two youngsters, capering away around the fire to the music.

Fred gives them tobacco and is mildly amused. On they play, apparently tireless. Pretty soon it’s past everyone’s bedtime, but still the concertina plays on.

“At last I had to turn out of my blankets and go for them with a

sjambok

,” he writes. “Only then did they quit, and I turned in again. But I had got a big thorn in my foot, and when I had got that out a scorpion got into my bed, and objected to my being there. Altogether a nice, quiet, idyllic night by the river.”

Fred Cornell mucked about up here for more than a decade, just one sniff away from the mother lode. He sailed to London to raise more finances for his prospecting, went for a drive in a sidecar motorcycle and was killed in a collision with a London taxi.

The honour of discovering the world’s largest treasure house of diamonds lay with other men, such as Dr Hans Merensky and his team of geologists. No matter for Fred:

“I have been richly compensated for the few discomforts and hardships I have experienced by the glorious freedom and adventure of the finest of outdoor lives, spent in one of the finest countries and climates of the world.”

Armed with all this lore and expectation, we presented ourselves at the Alexander Bay Mine Museum for a tour of the diamond workings.

“The diamonds, washed down the Orange River, mostly lie in a sediment of fossilised oyster shells,” explained the museum curator and tour guide, Helené Mostert. “To get to this sediment, one has to go through as much as 40 metres of sand and calcrete. Then you reach the gravel on the bedrock, which bears the diamonds.”

Most of the mining takes place in the sea off Alexander Bay these days, and the divers share their profits with Alexkor.

Helené told us what we couldn’t take in: no cigarette lighters, lipstick, lip ice, cellphones, skin cream or, of course, pigeons. She had packed a picnic basket (ostrich biltong, chilli bites and muffins) but warned us we had to eat the lot before coming out again.

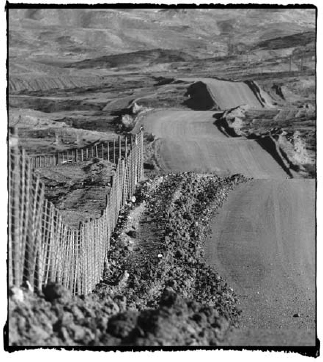

Alexander Bay society used to be divided into

binnekampers

and

buitekampers

(people who lived inside the restricted area and those who were outside the fence). Before leaving the area on weekend pass,

binnekamp

families and their possessions were thoroughly searched, because diamond smuggling in Namaqualand has always been as natural as truffle-hunting in France.

Despite the restrictions and the bleak landscape they lived in, the male workers used to have a rich old time of it. Namaqualanders are known for their prowess on the dance floor. The absence of women in the early days did not stop the men of Alexander Bay from having a roaring good stomp to an old tune on a Saturday night. Like their counterparts in the gold-mining boom in Barberton, they would ‘bull dance’ until the dawn, tossing each other about with much gusto. At the village of Grootderm, the local headmaster held bull dances for the miners in his school canteen.

And when the womenfolk started filtering into the community in later years, they would end up being flung onto the rafters by their enthusiastic male partners.

“Go dance with your friends,” was a refrain often uttered by rather bruised wives. Those were the days of beach parties, with giant lobster screeching in 200-gallon drums of boiling water, epic fishing expeditions and the occasional overdose of Cape Smoke, a particularly vengeful black sheep of the brandy family.

Namaqualand is a vast, barren area of little more than 120 000 souls, a place that gets a total of 50 mm of rain each year. That’s about equal to a couple of moderate Johannesburg thunderstorms. “God didn’t give us rain – He gave us diamonds” is the old Namaqualand saying. And, according to writer Pieter Coetzer in

Bay of Diamonds,

many locals openly admitted to illegally dealing in the stones.

But at Alexander Bay it’s still taboo to swing your tongue too freely around the word ‘diamond’.

“We were taught to always use the word ‘product’ when speaking about, er, diamonds,” said Pieter Koegelenberg, who had given a quarter of a century to ‘the bay’. Children playing ‘diamond in the sand’ games were told to use the word ‘pearl’ instead. We discovered that a diamond-mining camp (did they call it a ‘pearl-mining camp’?) was a place of paranoia.

If the slightest bit of suspicion arose about you and your character, you were packed out of the village before the morning paper arrived from Springbok. As in company towns all over the world, you had to adhere to a very strict code of behaviour.

In earlier years, if your wife was caught having an affair with another bloke, you were all kicked out of camp. No notice, no polite ‘first warning’. Just take the next bus south to Port Nolloth and don’t come back. And woe betide you if they found diamonds on the soles of your shoes.

Young Ernest from Pampierstad near Kimberley was assigned to be our guard, to ensure we didn’t suddenly bend down and slip a likely-looking stone into a secret place. In the company of Ernest and Helené we drove through the Gothicgrey mining complex, a rusted dreamscape scoured by 80 years of sand, wind, fog and rain. There was still much rehabilitation to be done out here, but, ironically, the mining operations had protected some pristine areas as well. We came across beautiful stretches of stark coastline that were home to colonies of seals and cormorants, with the occasional spotting of jackals, oryx and ostriches.

The harbour master, Alvin Williams, said that although his business was mainly with the little diamond boats (commonly called ‘Tupperwares’ or ‘tuppies’) moored below his office, a Chinese fishing trawler in distress was once allowed into these waters.

“It ran aground and caught fire,” he said. “They couldn’t speak English. Security officers had to somehow let them know they could just not walk around freely and they could definitely not pick anything up.”

I asked him if he’d ever been offered a bribe to look the other way when sweet diamond gravel was being brought up from the sea.

“Listen,” he said, his eyes boring into my head. “You can give me a bottle of brandy and half a sheep and we can go and have a nice

braai

together. But in the morning I’ll still be full of shit – even more so than before.” Alvin, I later found out, had grown up with a choice: be a gangster in the dangerous social waters of Cape Town’s District Six or go to sea. There was no

schlentering

on Alvin’s watch, because he knew all the tricks in the book of crooks.

For lunch we stopped over at the local oyster farm and ate the sweetest little molluscs in the world. I had mine with a dollop of Tabasco, while Jules downed hers neat. Oysters within sight of the sea – what magical fare.

Nearly three million oysters were being cultivated out here in lagoons, fed constantly by the cold West Coast upwellings. Helené said Alexander Bay also had wonderful lobster, and suddenly the lustre of diamonds briefly dimmed in comparison.

After a few hours of driving across the sandscape of the diamond fields, we returned to the security-clearance area for a long session in interleading rooms with smoky mirrors of X-ray searches, rubber gloves and pat-downs. Obviously our protests of innocence and our open, honest faces were not convincing enough for the eagle-eyed security staff of Alexkor.

“Don’t worry,” said Helené, as we nervously entered the search area. “Whatever happens in there, you will get out …”

We spoke to local residents of Alexander Bay, which is heaven on earth for a select group of hardy individuals such as Etienne Goosen, who spends his time riding waves on the sea and diving for diamonds in its depths.

“When we’re out there, it’s very physical, but the surfing also keeps you fit,” he said. “And when you’re on the boat, it’s really cool. You’re with your mates, chatting and hanging out together. It’s not really like work. The good thing is no one competes – we’ve all struggled at some time. We all know what it’s like. And we’re all generally incoherent by ten o’clock.”

Another local, oom Tommy Thomas, took out his fiddle and played a mournful version of ‘Amazing Grace’ for us in the middle of the street outside his home. And then he told us that the Namas of the Richtersveld would inherit Alexander Bay and her riches one day. How, I asked.

“Go and see the people in Khubus,” he said, mysteriously. I had the distinct feeling that all kinds of pigeons were coming home to roost …

Richtersveld

Sometime in 1960 the circus comes to Alexander Bay. It’s not the giant, tumbling caravan of bearded ladies, roustabouts, dancing elephants or six-foot ringmasters with booming voices that can summon snakes from deep holes. It’s just a little blue bread van trailing a folded tent. An old photograph – taken in the overexposed noonday light of the Richtersveld – shows the dusty vehicle, a side-on glimpse of the driver, a middle-aged midget on the running board and a brunette in a red button-down jersey next to him, an enigmatic smile playing on her face (or is she just squinting into the sun?). The sign on the van says

Marianis Mini Sirkus.

What was the show like? Who was the short person? Did the brunette do something intriguing on a trapeze? The two reigning circus midgets in South Africa at the time were Tickey the Clown and his rival, JoJo. But

those

guys came with skaters, jugglers, cowboy acts, bagpipes, a convoy of pantechnikon trucks, an army of roadies and a trampoline. And there probably

was

a woman with facial hair somewhere in that crowd. Marianis, in comparison, seems to have been a bit of a one-trick pony, but the records state that Alexander Bay received the mini troupe graciously.

This was a desert town that danced until floorboards broke, rated

Mutiny on the Bounty

as its all-time favourite flick and feasted off giant lobster and oysters. If you weren’t a fisherman up at Alexander Bay, people labelled you eccentric and you were probably given ‘the raised eyebrow’ as you passed on the street. The fishing was so good that a new manager, a total amateur with rod and reel, went off to the mouth of the Orange and caught himself a monster 24-kg cob one day.

“Even the fish are sucking up to the boss,” someone said.

Helené Mostert and her three-year-old son Gideon came to pick us up at the Frikkie Snyman Guest House just before dawn, in a 1978 vintage Land Rover. It was clear Gideon was hoping to inherit the old road warrior one day.