Silent Witnesses (20 page)

Authors: Nigel McCrery

Plate 9 By analyzing the composition and layering of soil collected on shoes and clothes, forensic scientists are able to build up a complete picture of where a suspect or victim has been. These techniques were already being developed over a century ago; in the case of Margarethe Filbert's murder in 1908, Georg Popp used soil found on Andreas Schlicher's shoes to disprove his alibi, which led to Schlicher giving a full confession.

Plate 10 A forensic investigator's case. Bernard Spilsbury first identified the need for standardized crime-scene kits following the gruesome “Murder at the Crumbles” in 1924. Today they are essential to any criminal investigation and contain a wide variety of equipment to allow evidence to be gathered safely and effectively.

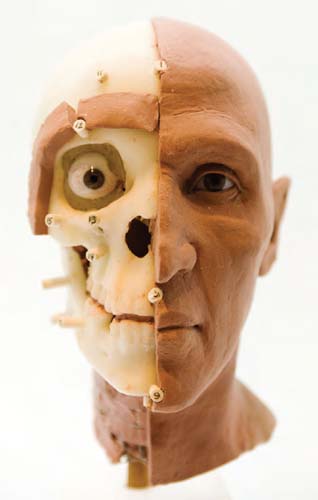

Plate 11 Facial reconstruction is now an important technique in establishing how decomposed remains might have looked when alive. The case of Buck Ruxton in 1935 employed similar methods, comparing the skulls of unidentified victims with known photographs of them to establish identity on the basis of similarity.

Plate 12 A newspaper illustration of Marie Lafarge at the time of her trial in July 1840. She was the first person to be convicted almost entirely on direct forensic toxicological evidence, after she apparently poisoned her husband to escape an unsatisfactory marriage.

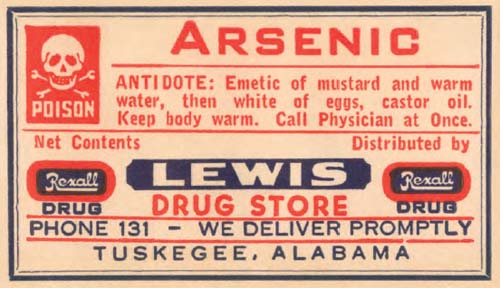

Plate 13 Label from a bottle of arsenic sold by a druggist in Alabama. In spite of its potentially lethal effects, for many years arsenic was available over the counter for a variety of household purposes.

Plate 14 A cheek swab being carried out by a detention officer in order to gather a DNA sample. The advanced techniques used today mean that even a sample this small can be used to construct a DNA fingerprint, which can then be compared against evidence found at a crime scene.

Plate 15 The Romanovs, the Russian imperial family, who were put to death in Yekaterinburg in 1918. When an unmarked mass grave was later discovered nearby, it was widely assumed that the bodies it contained

The Body

The human body is the best picture of the human soul.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

O

ne thing that every murder has in common is that it leaves behind a body. On an emotional level the physical remains of a human being can be hard for living people to face, particularly if they knew the deceased. While a corpse is clearly in some sense identical to the person who has died, and the violence done to a body is horribly evocative of their last moments, we are also keenly aware that there is something missing, that it is no longer fully a person. It is natural not to want to look closely at a dead body. However, as we have already seen in previous chapters, when studied in detail, a person's remains can yield a wealth of information.

When a body is discovered, the first job of the police is to try to identify it. As we have already seen, there are numerous ways to establish identity, though the most common today are for some form of ID to be found on the body, or for it to be recognized by a family member or friend. Of course the body

also constitutes the single greatest piece of evidence that a crime has been committed, and since in the majority of murder cases the killer is known to the victim, establishing the identity of the body can often guide police straight to the perpetrator. Criminals will therefore often go to great lengths to hide, destroy, or damage the body to prevent it being discovered and to ensure that, if it is, identifying it is extremely difficult.

However, human bodies are not easy to dispose of. They are difficult to burn or otherwise harm; bones and teeth are particularly resistant to damage. They float in water, often even when weighted down. When hidden, decomposing bodies quickly start to smell dreadful and to draw the attention of insects and other wildlife. They are easily sniffed out by dogs being walked by their owners. And with continuing advances in forensic science, even remains that stay hidden and decomposing for many years, to the point of becoming completely skeletal, are still able to offer vital clues as to their identity.

The Parkman-Webster murder case remains one of the most sensational in US legal history and provides a gruesome demonstration of the difficulties attendant on disposing of a body. It became a cause célèbre, largely on account of the horrible nature of the crime and the status of the people involved. It concerned the disappearance of a Bostonite, Dr. George Parkman, on the afternoon of November 23, 1849.

Parkman was a wealthy socialite, businessman, and philanthropist. He had a defined chin and wiry frame, and maintained a gentlemanly and restrained lifestyle. He worked hard, abstained from luxury, and was known for his amiable character. Fanny Longfellow, the poet's wife, labeled him “the good-natured Don Quixote.” He was not without his enemies,

however, with some viewing him as arrogant, money-grubbing, and vain. In 1849 he was worth approximately half a million dollars, a considerable fortune.

The other important figure in the case was John White Webster. Webster had graduated from Harvard in 1811 and in 1814 was among the founders of the Linnaean Society of New England. He went on to graduate from Harvard Medical College in 1815 and, after traveling extensively and marrying in 1818, returned to the college, having been appointed as a lecturer in chemistry, mineralogy, and geology. He was then appointed as the Erving Professor in 1821, reflecting his reputation as a popular and well-respected academic. The notable physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was a dean and contemporary of Webster's at Harvard, and commented on his affable, if nervous, demeanour in lectures.

Webster was also known to have serious financial problems, which were in part the reason he sold off the family home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1849, opting for a more modest rented residence instead. In spite of this downsizing, his salary was still not nearly enough to cover his expenses. The books he had written, being academic in nature, made little extra money. He had been forced to borrow from several of his friends and was now struggling to pay these debts.

Parkman was among the people who had loaned Webster money. In 1842 Webster borrowed $400 from him. Five years later this was increased to $2,432, this sum including the original loan. As a guarantee, Webster offered a cabinet of rare minerals. Unfortunately, by 1848 his situation had still not improvedâin fact it had worsened. He had to borrow again, this time $1,200 from a man named Robert Shaw. In spite of

the fact he had already offered it to Parkman a year previously, he once again used the cabinet of minerals as a guarantee. Unfortunately, Parkman found out about this bit of deceit and decided to confront Webster.

On November 22, 1849, Parkman visited Cambridge in search of Webster. When he was unable to find him, he called in on Mr. Pettee, the Harvard cashier, and demanded that he give him all the money Webster had made from the sales of his lecture tickets to go toward repaying his debt. Pettee refused, since he was not authorized to pay anyone but Webster. The following day Webster, clearly disturbed at this turn of events, visited Parkman at his house and suggested that they should meet at the college in order to talk the matter over. Parkman agreed. The last time he was seen alive was at 1:45

PM

on November 23, entering the college along North Grove Street. He was wearing a frock coat, dark trousers, a purple satin waistcoat, and his usual top hat.

When he failed to return home that day, Parkman's family reported him missing. Meanwhile Webster came home at 6

PM

before attending a party that evening at the house of some friends, the Treadwells. He seemed in good spirits and certainly showed no outward signs of distress.

A few days later, on November 26, Parkman's family offered a $3,000 reward for information leading to his being found. Twenty-eight thousand copies of a missing person notice were printed and posted all over the district.

At this point one of the college janitors, a man named Ephraim Littlefield, began to play an important role in the story. Littlefield lived with his wife in the basement of the medical college, right next to Webster's laboratory. Some

people had started to become suspicious of Littlefield, linking him to Parkman's disappearance. Littlefield, in turn, was becoming suspicious of Webster's behavior. He would later testify that, on the day of Parkman's disappearance, he had heard the sound of running water coming from inside Webster's rooms and found the door to them locked. He said that later that day he had seen the professor carrying some kind of bundle and that Webster had asked him to make up a fire. Webster had also asked him a number of questions about the dissecting vault.